You are viewing the article Yuri Kochiyama and Malcolm X’s Boundary-Breaking Friendship at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

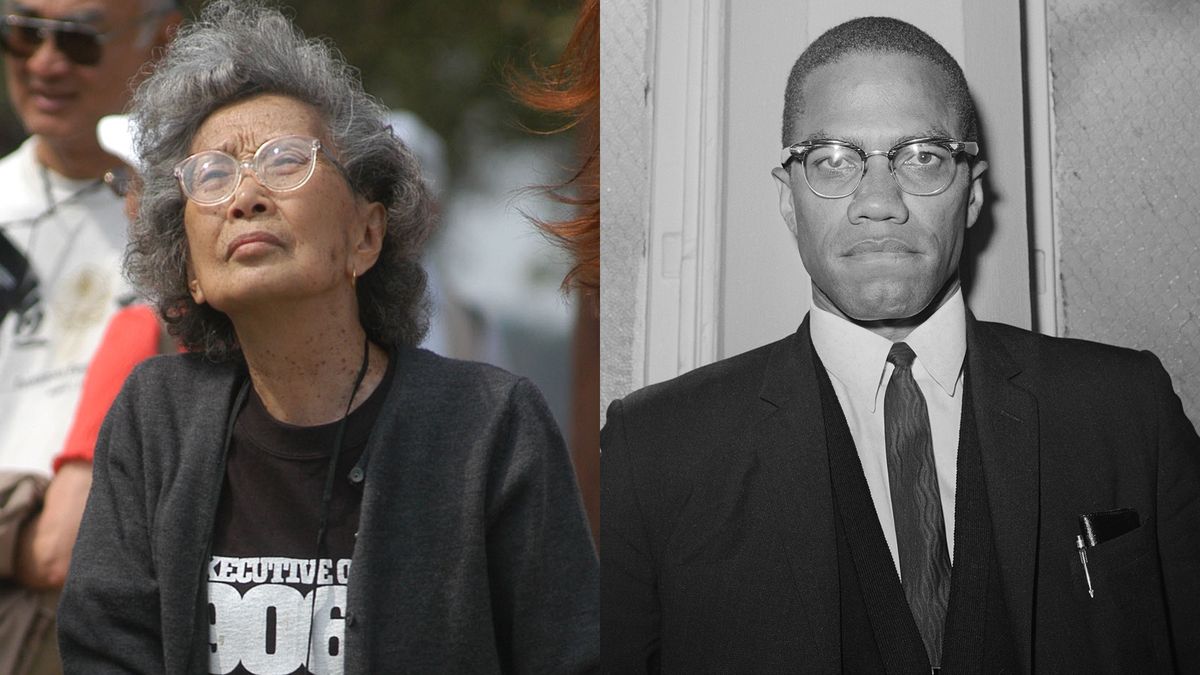

On paper, Yuri Kochiyama and Malcolm X made an unexpected pair — a Japanese American mother of six and a firebrand Muslim minister and Black nationalist. But their brief friendship, interrupted by his assassination in 1965, sheds light on the multi-racial cooperation of the civil rights movement and the broader fight against racial injustice around the world.

Kochiyama’s activism was sparked by her traumatic experiences during World War II

The daughter of Japanese immigrant parents, Mary Yuriko Nakahara was born in 1921 in San Pedro, California. Her father, Seiichi, was a successful fish merchant and the family lived a comfortable life in their predominantly white neighborhood.

But her life, and the lives of hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans and their families, were forever changed following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. That same afternoon, shortly after she returned home from church, her father was arrested by the FBI, thanks in part to an erroneous suspicion that Seiichi had been conspiring with Japanese officials, based on his lifelong friendship with Kichisaburo Nomura, an admiral in the Japanese Navy and the Japanese ambassador to the United States at the time of the attack. Seiichi was harshly interrogated during six weeks of detention and died just a day after he was released in January 1942.

The following month, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which ordered the forced removal of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. Like other Japanese families, the Nakaharas were forced to give up their livelihoods and possessions, and the family spent three years at an internment camp in Jerome, Arkansas. She would later describe herself as “apolitical” before the war. But her experiences, including her first glimpse of the racism faced by African Americans in the Jim Crow South, helped spark her lifelong fight for justice and civil rights.

READ MORE: 10 Inspiring Malcolm X Quotes

She became politically involved after moving to New York City

After marrying Bill Kochiyama, a Japanese American WWII veteran, the couple moved to NYC, where their growing family lived in a series of racially-mixed public housing projects, where Kuchiyama befriended her white, Asian, Latinx and Black neighbors.

After moving to Harlem in the early 1960s, she became increasingly active in the civil rights movement, joining groups like the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), attending programs at the Harlem Freedom School and participating in sit-ins to protest racism and inequality in both the United States and abroad. She encouraged her children’s involvement as well, taking the family on a 1963 trip to Alabama to see the physical scars of recent racial protests in Birmingham.

Her politics became more radical after befriending Malcolm X

In October 1963, Kochiyama and her teenaged son Billy attended a Brooklyn rally in support of workers protesting unjust hiring practices. She and dozens of others were detained by police, and while she was waiting in the courthouse, she saw Malcolm X arrive to give his support to the predominately Black group of protesters. Initially reluctant to intrude on what she considered an important encounter for the Black youth in the group, she eventually worked up the courage to introduce herself. As she would later recall, she told him she admired his work but disagreed with his opposition to racial segregation, which had made him a controversial outlier to the more mainstream civil rights movement.

Perhaps impressed by her willingness to challenge his positions, Malcolm and Kochiyama soon bonded. He encouraged her to more deeply involve and educate herself about the long history of racial oppression, and she attended a school program he had set up and later joined his newly-created Organization of Afro-American Unity. She also briefly converted to Islam and would credit Malcolm with changing her world view, later telling an interviewer, “He certainly changed my life. I was heading in one direction, integration, and he was going in another, total liberation, and he opened my eyes.”

They met during a tumultuous period in Malcolm’s life

Just months after their meeting he would break up with the Nation of Islam due to tensions with its leader, Elijah Muhammad. In the spring of 1964, he embarked on a tour of Africa and the Middle East that had a profound impact on his thinking, as he began to shift away from his more militant positions that had encouraged African Americans to battle racism with “any means necessary” to the openness to explore peaceful resolutions to the nation’s racial problems. He corresponded with the Kochiyamas during his trip, sending them a series of postcards documenting his travels.

Shortly after his return, he visited the Kochiyamas’ Harlem apartment, where he met with a group of Japanese survivors of the American bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki who were part of an international group of peace advocates. He spoke of the devastating effects of both racism and American imperialism around the world, noting, “You were bombed and have physical scars. We too have been bombed and you saw some of the scars in our neighborhood. We are constantly hit by the bombs of racism — which are just as devastating.”

Kochiyama cradled Malcolm X’s head following his assassination

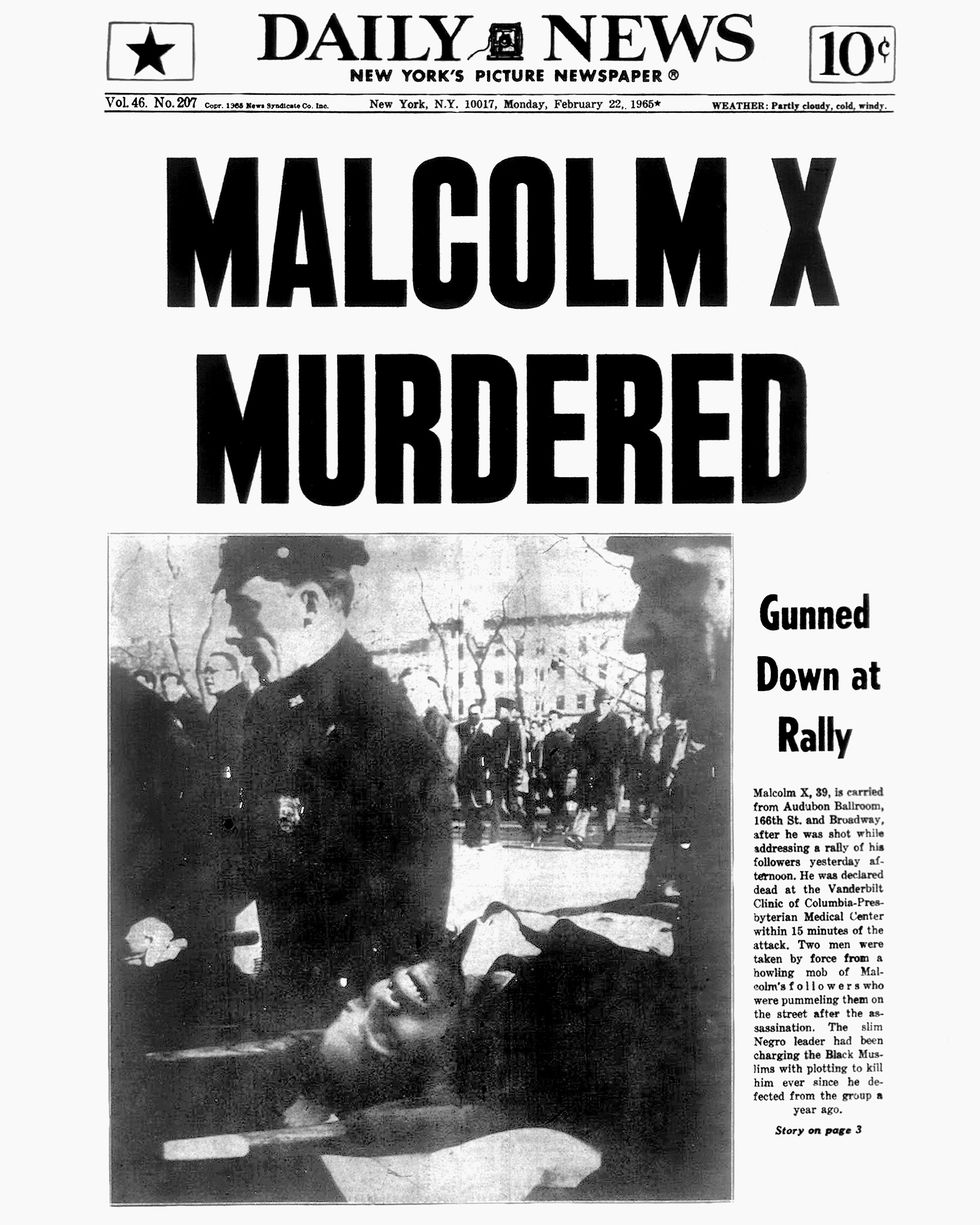

On February 21, 1965, just 16 months after their first meeting, Kochiyama attended a speech Malcolm was set to deliver at New York’s Audubon Ballroom. Rumors and threats against Malcolm’s life had become common, and Kochiyama would later recall that tensions in the room were high. A scuffle that broke out in the crowd is believed to have been a planned diversion, which successfully distracted the attention of the guards hired to protect Malcolm.

As he stood on the stage to begin his speech, multiple men rushed forward and began firing, shooting him repeatedly at close range before fleeing the room. The shocked crowd, which included Malcolm’s pregnant wife, Betty Shabazz, and their children, broke into bedlam, and when Kochiyama saw another man running towards the stage to help, she followed him. A Life magazine photographer quickly captured the now-iconic photo of Kochiyama cradling Malcolm’s head as people struggled to save his life, and as she urged him, “Please, Malcolm, please, Malcolm, stay alive.” Kochiyama would make an annual pilgrimage to Malcolm’s upstate grave every May, in honor of their shared May 19 birthdate.

READ MORE: The Assassination of Malcolm X

Despite her devastation over Malcolm’s death, Kochiyama remained an activist

For several decades, the Kochiyamas’ apartment became something of a nerve center for Black nationalists and other left-leaning groups. Her children recall leaflets and documents covering every available surface and the constant comings and goings of political leaders. As her daughter Audee would later recall, “Our house felt like it was the movement 24/7.” Among the guests were activist Angela Davis, poet Amiri Baraka and a young Tupac Shakur, the son of activist and Black Panther member Afeni Shakur.

Kochiyama was the frequent subject of controversy thanks to her support of many socialist and radical causes, including backing a brutal Peruvian terrorist group and expressing her admiration for Osama bin Laden in a 2003 interview. Despite this, she was part of a group of 1,000 global women activists who were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2005.

Of the causes she championed, the most personal was the fight for reparation for Japanese Americans, like herself, who had been detained in relocation camps during World War II. For decades, she and her husband were among those fighting for recognition from the U.S. government. Finally, in 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which included a presidential apology for the wartime detainments, and a $20,000 payment to each surviving detainee.

Thank you for reading this post Yuri Kochiyama and Malcolm X’s Boundary-Breaking Friendship at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: