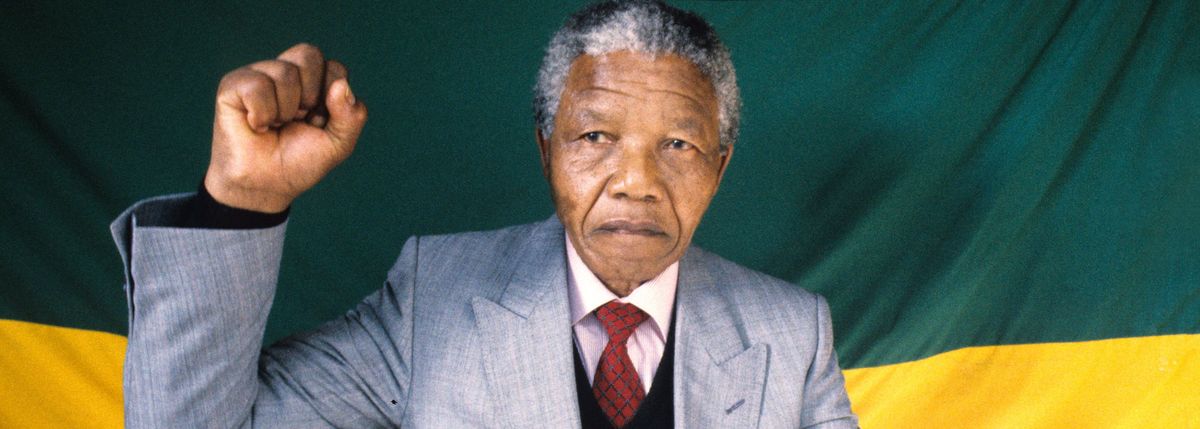

You are viewing the article Why Nelson Mandela Was Viewed as a ‘Terrorist’ by the U.S. Until 2008 at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Former U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher thought that Nelson Mandela had “rather a closed mind,” according to recently released records at the U.K. National Archives. The prime minister made the comment after a phone call with Mandela in July 1990, only five months after the anti-apartheid leader was released from jail.

But although Thatcher’s newly revealed comments may be shocking, they’re no surprise considering how she and her U.S. counterpart viewed Mandela and his political party, the African National Congress.

Both Thatcher and U.S. President Ronald Reagan accused Mandela and the ANC of being communists and terrorists in the 1980s, and Reagan’s administration even placed Mandela and the ANC on a terrorist watch list. The U.S. and U.K. leaders considered South Africa’s apartheid regime to be a Cold War ally, and the opposing ANC to be an enemy bent on spreading communism.

“The South African government is under no obligation to negotiate the future of the country with any organization that proclaims a goal of creating a communist state, and uses terrorist tactics and violence to achieve it,” Reagan said in a 1986 speech.

He and Thatcher opposed sanctioning the South African government, a move that Mandela and the ANC supported because it would put pressure on the country to end apartheid.

Even as Thatcher urged Mandela’s release, she publicly condemned the ANC and privately dismissed Mandela. “A considerable number of the ANC leaders are communists,” she told a press conference. “When the ANC says that they will target British companies, this shows what a typical terrorist organization it is.”

In 2016, The Timesobtained documents alleging that her administration tried to prevent a royal family member from giving Mandela an honorary degree.

Not all heads of state held this view. Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney struggled unsuccessfully to convince the U.S. and U.K. leaders that Mandela and the ANC weren’t their enemies in the Cold War.

“Ronald Reagan saw the whole South African issue strictly in East-West Cold War terms,” Mulroney wrote in his memoirs. “Over the years, he and Margaret continually raised with me their fears that Nelson Mandela and other anti-apartheid leaders were communists. My answer was always the same. ‘How can you or anyone else know that?’”

Still, Thatcher and Reagan weren’t the only politicians in their countries who saw Mandela and the ANC as terrorists. On ABC’s This Week in 2000, Dick Cheney defended voting against a 1986 House bill urging South Africa to release Mandela because “the ANC was then viewed as a terrorist organization.”

In the mid-80s, a member of Parliament named Terry Dicks said “Nelson Mandela should be shot” and asked, “How much longer will the Prime Minister allow herself to be kicked in the face by this Black terrorist?”

In addition to maligning Mandela and the ANC, Reagan actively praised South Africa’s apartheid regime. In 1981, he told Walter Cronkite South Africa was “a country that has stood by us in every war we’ve ever fought, a country that, strategically, is essential to the free world in its production of minerals.”

In 1985, Reagan incorrectly told a radio interviewer that “they have eliminated the segregation that we once had in our own country.” In reality, the country didn’t begin dismantling segregation until apartheid ended in 1994.

Mandela continued to deal with these attitudes in the U.S. and U.K. after his release from prison in February 1990. In addition to Thatcher’s opinion that he had “rather a closed mind,” The Heritage Foundation — a prominent American conservative group — accused him of being a communist supporter of terrorism the week before he visited the United States.

Conservative media and think tanks continued to smear him this way as late as 2003, when the National Review wrote it was no surprise Mandela opposed the Iraq War “given his long-standing dedication to Communism and praise for terrorists.”

Succeeding leaders in the U.S. and U.K. had more favorable views of Mandela, who became South Africa’s president in 1994. Even so, the U.S. continued to classify Mandela and his party as terrorists until 2008. That July, President George W. Bush signed a bill removing them from all terrorist lists.

Before this, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice had to personally approve visits from South African leaders, and she told a Senate committee: “it’s frankly a rather embarrassing matter that I still have to waive in my own counterpart, the foreign minister of South Africa, not to mention the great leader Nelson Mandela.”

Thank you for reading this post Why Nelson Mandela Was Viewed as a ‘Terrorist’ by the U.S. Until 2008 at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: