You are viewing the article Why Jimmy Carter Ordered the U.S. to Boycott the 1980 Olympics at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

By late 1979, as he headed into the fourth year of an administration marked by lagging domestic support, President Jimmy Carter found himself facing a new set of challenges from foreign agitators.

In November, more than 60 people were taken hostage at the U.S. Embassy in Iran. Then, in late December, the Soviet Union reignited Cold War tensions by invading Afghanistan to prop up a Communist regime.

Seeking to take a strong stance on the global stage, Carter threatened Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev with a grain embargo and the removal of the SALT II treaty from Senate consideration. He also considered pulling the United States from participating in the 1980 Summer Olympics, to be held in the Soviet capital of Moscow, a move that packed a strong public-relations punch but potentially left him vulnerable to a powerful backlash.

Carter Announced His Boycott Threat on Meet the Press

According to U.S. Department of State archives, the idea of an Olympic boycott had materialized during a NATO meeting on December 20, 1979, a few days before the Soviet invasion. With Soviet dissidents like Nobel laureate Andrei Sakharov championing the boycott, the topic gained steam in the press and within the Carter administration, although the president reportedly felt “cold chills” when seriously weighing whether to follow through on the action.

Carter rendered his ultimatum during the January 20, 1980, episode of Meet the Press, demanding the Olympics be moved to an alternate site or canceled if the Soviets didn’t withdraw their troops within one month. “Regardless of what other nations might do, I would not favor the sending of an American Olympic team to Moscow while the Soviet invasion troops are in Afghanistan,” he said.

Three days later, the president again brought up the subject to a national audience during his State of the Union address, drawing a rousing response for declaring that “neither the American people nor I will support sending an Olympic team to Moscow.”

He Sent Muhammad Ali to Garner Support in Africa

Despite the tough posturing, Carter knew he could wind up with egg on his face if other countries didn’t back the boycott. Underscoring the uncertainty of his goal, he dispatched Muhammad Ali as an ambassador to drum up support across Africa, where the normally popular boxer encountered a largely frosty reception.

There was also the matter of winning over the American athletes, who technically answered to the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), not the government. The president did have legal maneuvers at his disposal, namely, the seizure of passports, though that sort of strong-arm tactic ran the risk of torpedoing public support.

Further complicating things was the successful staging of that year’s Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York, which included the U.S. men’s hockey team’s “Miracle on Ice” win over the fearsome Soviet squad—an effort that bolstered the anti-boycott argument that competition was the best way to settle geopolitical disputes.

The USOC Agreed to the Boycott after Intense Lobbying

With Brezhnev refusing to pull his military from Afghanistan, and the International Olympic Committee unwilling to reschedule the Summer Games, the onus was on the Carter administration to get the American athletes in line.

Convening a meeting with USOC members at the White House on March 21, National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski delivered a presentation that highlighted the dangers of the Soviet invasion, including its alleged use of chemical weapons.

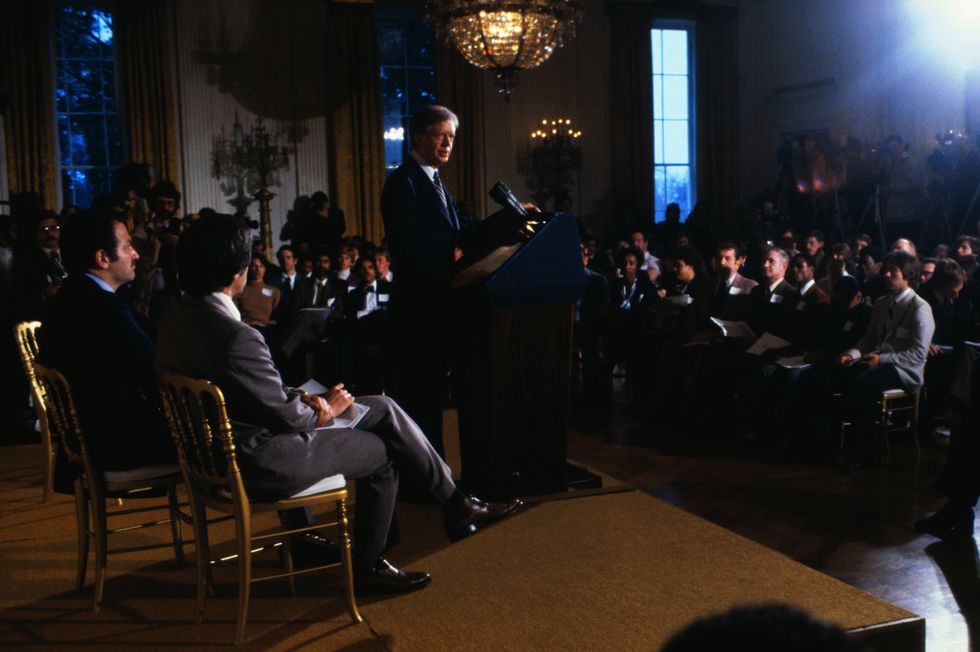

President Carter then entered the room, the news cameras capturing the tense moment as he followed through on his ultimatum. “I can’t say at this moment what other nations will not go to the Summer Olympics in Moscow. Ours will not go,” he stated. “I say that not with any equivocation; the decision has been made.”

Still, the decision wouldn’t be set in stone until the USOC endorsed the boycott. Following impassioned speeches from Vice President Walter Mondale and former treasury secretary William Simon, the USOC voted on April 12 to forego the competition, though several members grumbled about having no choice in the matter.

Ultimately, 64 countries joined the U.S. in boycotting the Summer Games that August, with another 80 heading to Moscow—including American ally Great Britain, which elected to let its athletes decide for themselves whether to participate.

American Athletes Remain Bitter over the Loss of Olympic Opportunity

Carter attempted to make amends with the U.S. Olympians by awarding each of them a congressional gold medal that summer. The administration also followed through on promises to stage alternate events, such as the Liberty Bell Track and Field Classic held in Philadelphia.

But the question of whether the president made the right call remains open for debate. The boycott didn’t help him politically, as Ronald Reagan unseated Carter from the White House at the end of the year. It also seemingly had little effect on policy, with the Soviets returning the favor by boycotting the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles and retaining a military presence in Afghanistan until 1989.

Carter has since publicly defended his decision, but the fallout was felt most acutely by those athletes who had nothing to show for years of intense training for Olympic glory. Rower Anita DeFrantz, who led a failed lawsuit against the USOC in 1980, later referred to the boycott as “a pointless exercise and a shameful part of U.S. history.”

And runner Steve Paige, a strong contender for a medal in the 800 meters, recalled the heartbreak he felt in a 2012 interview with CNN, before adding, “I got my revenge—I became a Republican that year.”

Thank you for reading this post Why Jimmy Carter Ordered the U.S. to Boycott the 1980 Olympics at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: