You are viewing the article Why Bob Dole Was Often Seen Clutching a Pen at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Just like hosting town hall meetings and kissing babies, shaking hands is a must for politicians on the campaign trail. But that last part was tricky for Bob Dole.

The veteran lawmaker who spent eight years serving Kansas in the U.S. House of Representatives and 27 years in the Senate, suffered severe injuries, including a debilitating one to his right hand, during his service in World War II, forcing him to find a way to avoid using it.

Dole’s platoon came under attack and he didn’t know if he was going to survive

Dole, who enlisted in the Army in 1942, was called up in 1943, and, fresh out of officer candidate school, was shipped out for an unknown destination in December 1944, was assigned to a camp of replacement officers outside Rome, Italy.

“The army assigned me to the front in the Apennine Mountains, to take over a platoon, replacing an officer who had been with the 10th Mountain Division,” Dole writes in his autobiography, One Soldier’s Story.

At age 21, on April 14, 1945, two days after the death of President Franklin Roosevelt and just a few weeks before the Nazi surrender, Dole’s platoon came under attack by the Germans, and, trying to take out Nazi machine gunners, he was hit in the back. “As the mortar round, exploding shell, or machine gun blast — whatever it was, I’ll never know —ripped into my body, I recoiled, lifted off the ground a bit, twisted in the air, and fell face down in the dirt,” he writes.

“For a long moment I didn’t know if I was dead or alive. I sensed the dirt in my mouth more than I tasted it. I wanted to get up, to lift my face off the ground, to spit the dirt and blood out of my moth, but I couldn’t move. I lay facedown in the dirt, unable to feel my arms. Then the horror hit me — I can’t feel anything below my neck! I didn’t know it at the time, but whatever it was that hit me had ripped apart my shoulder, breaking my collarbone and my right arm, smashing down into my vertebrae, and damaging my spinal cord.”

He held a pen in his right hand to make the ‘hand appear normal’

Eventually rescued by medics, Dole’s injuries were grave, requiring multiple operations over three years, including several by Dr. Hampar Kelikian, an Armenian refugee and pioneer in the surgical restoration of arms and legs, who refused to take money for his services but was able to relieve most of the pain and return some function to Dole’s arms.

Dole slowly regained mobility, but much of the damage to his arms and hands was irreversible.

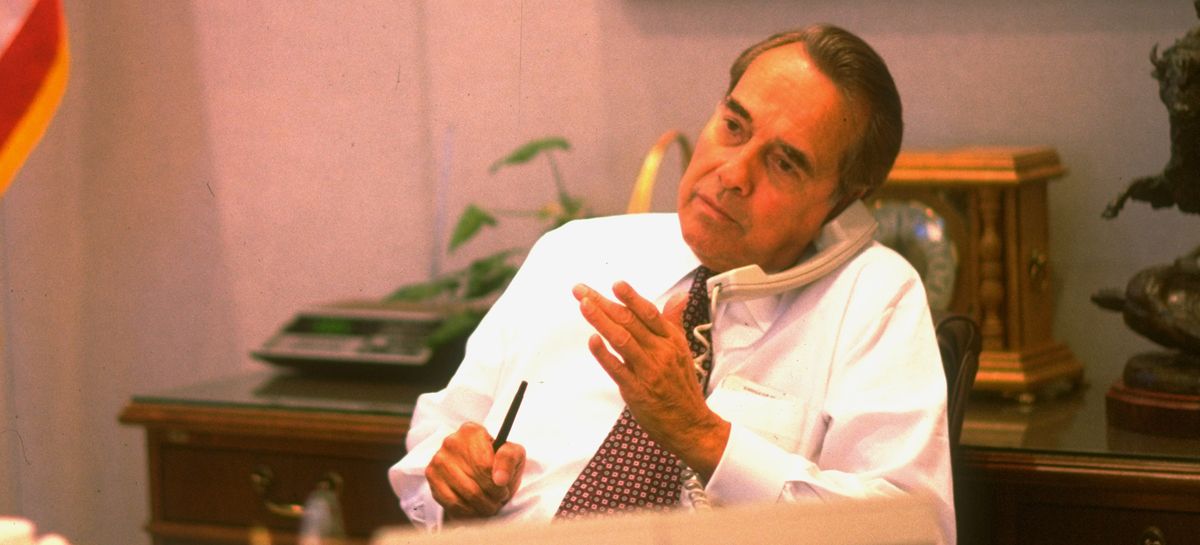

“His right hand was basically unusable and, as a person running for office, he found everybody was trying to shake his right hand and it would cause him pain,” says Bill Lacy, director of the Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics at the University of Kansas. “And so he started putting a pen or a pencil in his hand so people wouldn’t grab it.”

During his recovery, increasingly, Dole writes, the fingers on his right hand would close into a ball. But he found that if he could wrap them around a rolled-up piece of paper, it would slow people from rushing to shake his hand.

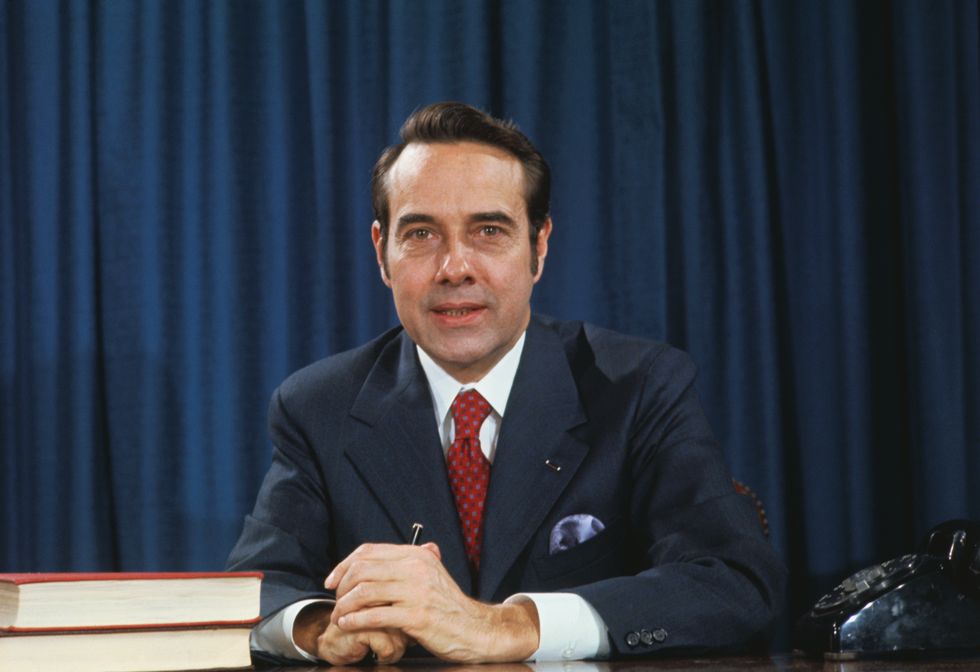

“I eventually discovered that by holding a pen in the hand, grasping it between my thumb and forefinger and wrapping the remaining three fingers around the shaft of the pen, I made the hand appear normal,” he writes. “For nearly six decades now, if you’ve seen me on the political campaign trail, in the U.S. Senate, in an interview, joking with Jay Leno on television, in a commercial, visiting with our troops, or anywhere, you’ve perhaps noticed that the pen is always there. It has become a part of my right arm.”

Lacy says the injury also meant Dole had to sign everything with his non-dominant left hand.

“He got better at it through the years, but you couldn’t really read a lot of what he wrote,” he says. “There were some people in his office who were very valuable because they could read his writing.”

And while Dole does shake with his left hand, that’s not without effort, either.

“To this day, one of the best-kept secrets regarding my war wounds has been the damage to my left arm and hand,” Dole writes. “Over the years, I’ve shaken hands with so many people using my left hand that most people assumed that the hand is fine. Actually, I have no more feeling in those fingers today than I did in June 1945, and the left hand is extremely sensitive. After shaking hands with a few too many folks, my left hand starts turning black and blue, much as it did sixty years ago.”

Dole’s injury fueled his desire to enter politics and help the less fortunate

Dole’s military experience had an enormous impact on his political career, Lacy says.

“Here is a man who, effectively left for dead on the battlefield, survives, undergoes multiple surgeries and comes back from the war with his body shattered,” he says. “But his spirit is obviously very, very strong, and he basically willed himself back to health.”

Eventually returning to Kansas, Dole, who was a basketball and track athlete at Kansas University before the Army, enrolled at Washburn University near Topeka where he finished his degree and graduated from law school before winning his first seat in public office in 1950.

“I think, more than anything, that what happened to him in the military showed him that he was capable of overcoming anything,” Lacy says. “It showed him something he had never thought much about before, which is that there are people going through life who have disadvantages that are no fault of their own.”

Lacy says Dole’s injuries also fundamentally change his outlook on life.

“If you look at his legacy and his career, even though he was a fairly staunch conservative, he has always been very much focused on helping those who can’t help themselves — looking after veterans, looking after senior citizens, helping African Americans to be able to exercise their right to vote with fewer restrictions and civil rights laws,” he says. “And he looked after animals who can’t defend themselves — he had a very strong legacy and record on animal welfare.”

Years later, Dole writes in his book, someone asked Kelikian why he never gave up on his patient.

“He would respond in his still broken English, ‘This young man…had the faith to endure,’” Dole writes. “To me, Dr. Kelikian’s comment was one of the greatest honors I’ve received in my life.”

Thank you for reading this post Why Bob Dole Was Often Seen Clutching a Pen at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: