You are viewing the article W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington Had Clashing Ideologies During the Civil Rights Movement at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

No account of Black history in America is complete without an examination of the rivalry between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, which in the late 19th to early 20th centuries changed the course of the quest for equality in American society, and in the process helped give birth to the modern civil rights movement. Though Washington and Du Bois were born in the same era, both highly accomplished scholars and committed to the cause of civil rights for Black people in America, it was their differences in background and method that would have the greatest impact on the future.

Washington believed Black people should have economic independence

Born into slavery in Virginia in 1856, Washington’s early life and education did much to influence his later thinking. After the Civil War he worked in a salt mine and as a domestic for a white family and eventually attended the Hampton Institute, one of the first all-Black schools in America. After completing his education, he began teaching, and in 1881 he was selected to head the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama, a sort of vocational school that sought to give African Americans the necessary moral instruction and practical work skills to make them successful in the burgeoning Industrial Revolution.

Washington believed that it was economic independence and the ability to show themselves as productive members of society that would eventually lead Black people to true equality and that they should for the time being set aside any demands for civil rights. These ideas formed the essence of a speech he delivered to a mixed-race audience at the Cotton State and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895. There and elsewhere, his ideas were readily accepted by both Black people who believed in the practical rationality of his approach, and white people who were more than happy to defer any real discussion of social and political equality for Black people to a later date. It was, however, referred to pejoratively as the “Atlanta Compromise” by its critics. And among them was Du Bois.

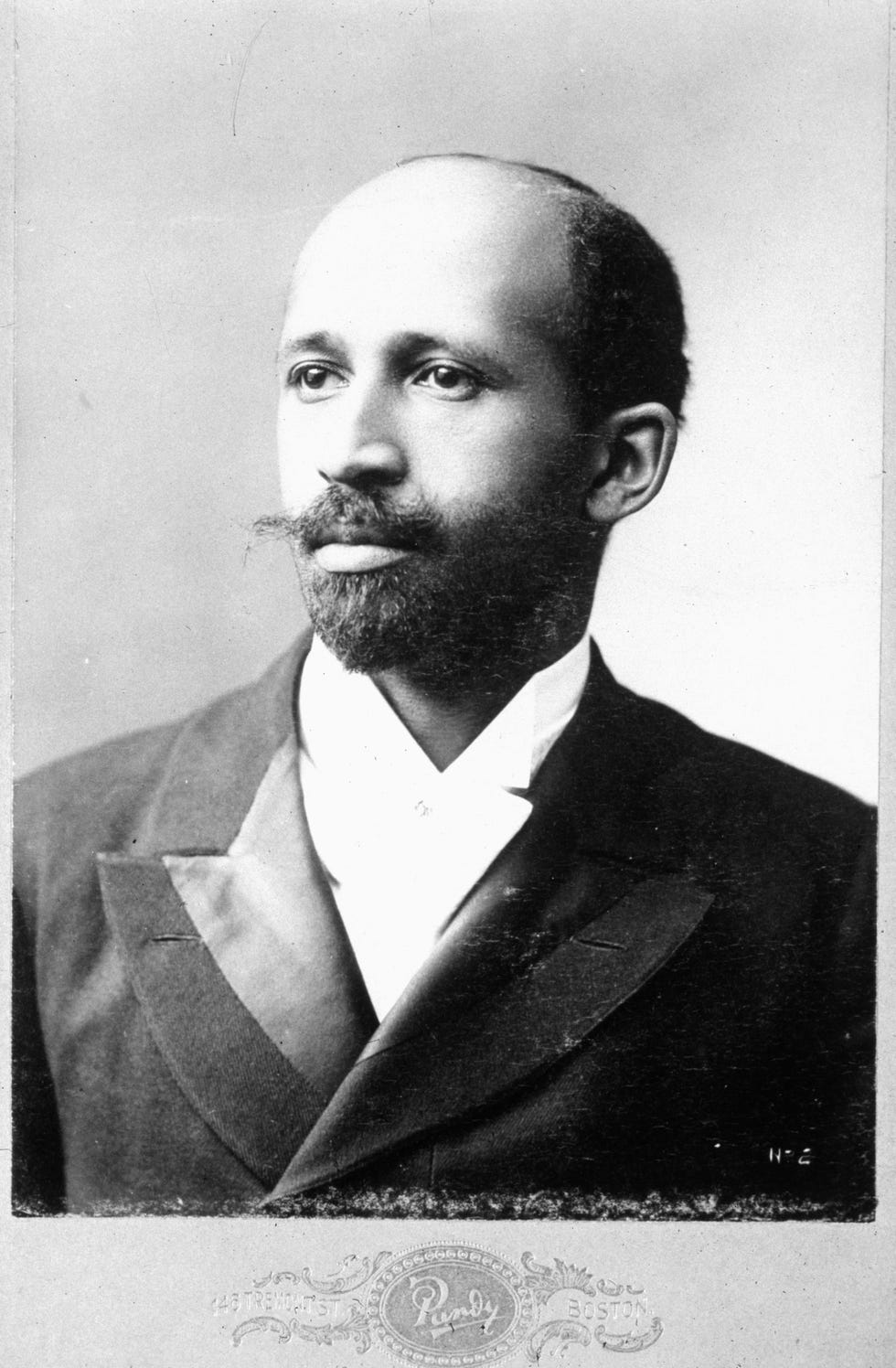

Born to a free Black family, Du Bois first experienced bigotry in college

Du Bois was born in 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, to a free Black family in a comparatively integrated community. He attended the local schools and excelled in his studies, eventually graduating as valedictorian of his class. However, when in 1885 he began attending Fisk University in Tennessee, he encountered for the first time the open bigotry and repression of the Jim Crow South, and the experience had a profound impact on his thinking. Du Bois returned to the North to further his education, with nothing less than equal rights for Black Americans being his ultimate goal. When he earned his Ph.D from Harvard University in 1895, he was the first Black man to have done so, and his dissertation, “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638–1870,” was one of the first academic works on the subject.

Washington and Du Bois’ ideologies clashed

By the early 20th century, Washington and Du Bois were the two most influential Black men in the country. Washington’s conciliatory approach to civil rights had made him adept at fundraising for his Tuskegee Institute, as well as for other Black organizations, and had also endeared him to the white establishment, including President Theodore Roosevelt, who often consulted him regarding all matters about Black people.

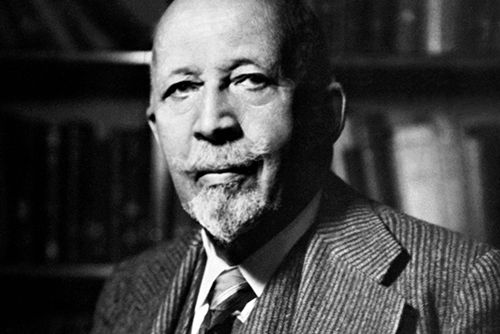

On the other hand, Du Bois had by that time become the country’s foremost Black intellectual, having published numerous influential works on the conditions of Black Americans. In contrast to Washington, Du Bois maintained that education and civil rights were the only way to equality and that conceding their pursuit would simply serve to reinforce the notion of Black people as second-class citizens. Following a series of articles in which the two men expounded on their ideologies, their differences finally came to a head when, in 1903, Du Bois published a work titled The Souls of Black Folks, in which he directly criticized Washington and his approach and went on to demand full civil rights for Black people.

More than just deepening the personal dislike between Washington and Du Bois, this ideological rift would in time prove to be one of the most important in the history of the struggle for civil rights. Believing that political action and agitation were the only way to achieve equality, in 1905 Du Bois and other Black intellectuals founded a political group called Niagara, which was dedicated to the cause. Though the group eventually dissolved a few years later, in 1909 several of its members and many of its aims were incorporated into a new organization — the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). For the next 25 years, Du Bois would serve as its director of publicity, as well as the editor of its journal, Crisis, which became the mouthpiece for the organization, for Du Bois and for Black America in general.

READ MORE: How W.E.B. Du Bois Helped Create the NAACP

When President Woodrow Wilson assumed office in 1913, he immediately segregated the federal government, and Washington consequently lost the political influence he had enjoyed for the previous decade. Washington died in Tuskegee, Alabama, on November 14, 1915.

Du Bois eventually split from the NAACP, but he continued to champion the cause of civil rights for both African Americans and the African diaspora around the world. After joining the American Communist Party in 1961, Du Bois repatriated to Ghana and became a naturalized citizen. He died in Ghana on August 27, 1963, at the age of 95. Martin Luther King Jr. led the March on Washington the next day.

Thank you for reading this post W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington Had Clashing Ideologies During the Civil Rights Movement at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

_Associated_Press_Wikimedia_Commons?resize=980:*)