You are viewing the article Tim McGraw Didn’t Meet His Dad Tug Until He Was 11. Inside Their Complicated Relationship at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

It was like something out of a country-music song: Two young adults, one a 21-year-old professional baseball pitcher, the other an 18-year-old aspiring dancer, meeting in a steamy Florida summer amid good times by the pool. Nine months after their summer fling, the dancer gives birth to a son. With the father wanting no part of the child, he turned his back on the baby and his mother to chase dreams of baseball stardom.

But this was no honky-tonk tune about unwanted souls and unfair lives. This is the true story of baseball star Tug McGraw and his first son, country music giant Tim McGraw. And despite the inauspicious beginnings, the two managed to close what could have been an unbridgeable gap and even grow tight before Tug’s fatal illness ended their time together.

Tim his father’s identity after finding his birth certificate

Tim grew up in Start, Louisiana, believing his name was Tim Smith. His mother, Betty, was married to a truck driver named Horace Smith, who installed in Tim a love for country music before their difficult marriage ended in divorce a few years later.

Meanwhile, Tug had emerged as one of the premier relief pitchers in Major League Baseball, celebrated for his hard-to-hit “screwball” and rallying slogan of “Ya gotta believe!” that became the catchphrase of the 1973 Mets. He was also known as something of a screwball himself – his wacky personality earning a legion of young fans that included Tim Smith, who pinned a baseball card of the pitcher to his wall.

As described in Tug’s posthumous memoir, an 11-year-old Tim was rummaging through his mom’s closet for Christmas gifts when he came upon his birth certificate with a scribbled-out section that mentioned a baseball-playing father. He called his mom, who confessed that Tug, now a pitcher for the Philadelphia Phillies, was his father.

Tug agreed to meet but would not acknowledge paternity

Betty then called Tug for the first time since their summer fling and told him what had happened. Anticipating the call, though he had doubts about being the father, Tug agreed to meet when the Phillies traveled to Houston.

Sharing lunch at a hotel bar, Tug recalled Tim as “very shy” and “well mannered,” and although the boy was likeable, the ballplayer was now married with two other children and had no interest in welcoming another into his life. He told Tim to consider him a “buddy,” not his father, and later suggested to Betty that it would be best if they kept their lives separate.

Ignoring his request, Betty tried to get them all to meet again in Houston the following year. Tug left tickets but refused to partake in any private get-together and ignored Tim when the 12-year-old called out to him from the stands.

They forged a relationship by the end of Tim’s high school years

While Betty gave up hope, Tim continued to send his father letters, even as they failed to generate responses. And as he matured into his teen years, his mother struggling to adequately feed and shelter her three children, he began musing on the disconnect between his absent father’s success and the rest of his family’s difficulties.

The resentment didn’t affect him in high school, as he became a star multi-sport athlete and class salutatorian, though the lack of finances threatened to limit his college options. In early 1985, after Tug announced his retirement, Tim suggested to his mom that it was time for his dad to step in and help. Betty agreed, and she soon caught Tug’s attention with a letter from the State of Louisiana demanding $350,000 in back child support.

Tug’s lawyer and Betty negotiated a figure of $42,000 for undergraduate and law school, but as part of the deal – which would finally include a paternity test to settle the matter – Tim would have to cease all attempts at contacting Tug and his family. Tim said he would consider, but only if he could meet his dad face-to-face again.

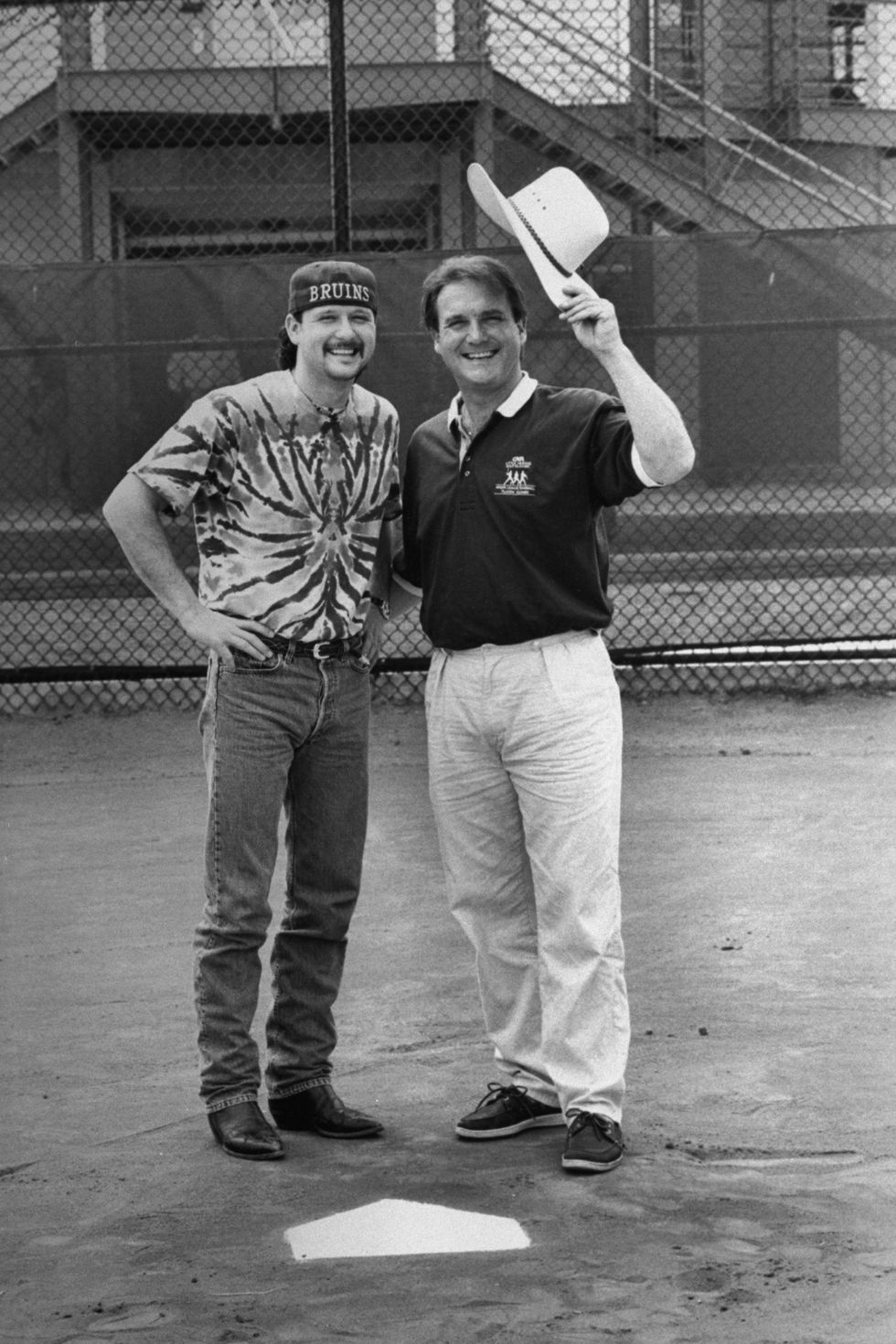

This time, according to Tug, he took one look at the 6-foot teenager ambling toward him, the facial resemblance undeniable, and said the paternity test was unnecessary. Stretching the day out of the course of lunch, tennis and dinner, the two agreed they would put their rocky past behind them and move forward as father and son.

Tug tried to pay Tim back by helping with his career

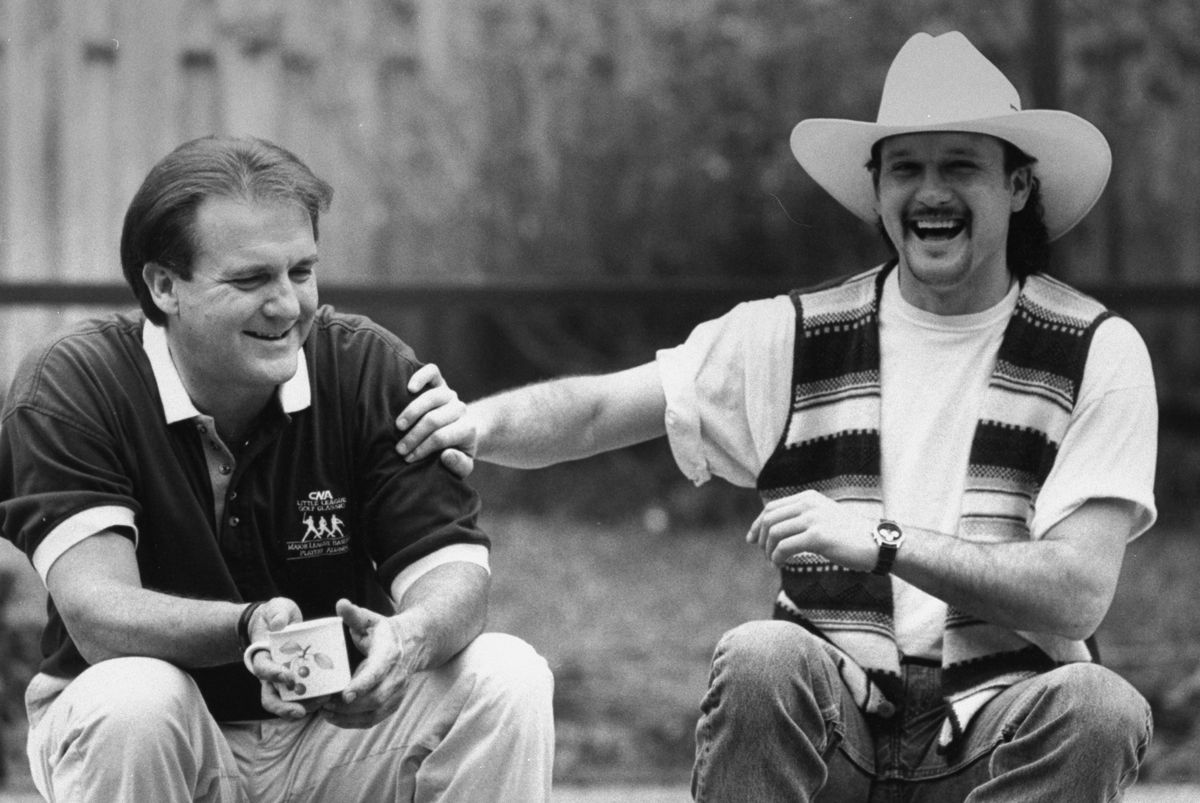

Despite the mutual understanding, the years of separation weren’t quickly overcome, with Tug noting they still seemed to be at “arm’s length” when partying at Mardi Gras together during Tim’s sophomore year of college. Tug attempted to give fatherly advice once, in an attempt to discourage Tim from dropping out to pursue a music career, though his argument fell apart when it was pointed out he had also left school to become a baseball player.

But Tim acknowledged the ties by formally changing his last name to McGraw, while Tug realized he could pay his son back a little for all those years of denial. During a 1990 team party for the Phillies, he met an executive from Nashville’s Curb Records, who listened to Tim’s demo tape on the ride home. The younger McGraw soon had a deal with the record label. Tug also bought Tim a van to fit his eight-member band and helped find suitable venues for their performances.

Within a few years, Tim no longer needed his dad’s financial support, as his breakout 1994 album Not a Moment Too Soon and 1996 marriage to fellow country crooner Faith Hill cemented his place as an industry star. Ironically, after years of refusing to accept that Tim McGraw was his son, the elder was now known to a large share of the population as Tim McGraw’s dad.

Tim saw his dad through brain cancer treatment

The final act in their shared story came in 2003, after a wobbly Tug was found to have tumors growing in his brain. Told his dad had three weeks to live, Tim declared that outlook “unacceptable” and had him transferred to the Moffit Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, for an operation and treatment. He found Tug a nice home for recuperation in Tampa and then another back in Philadelphia, checking in with phone calls delivered live from a concert stage.

Later that year, when it became clear that they were running out of options at the Moffitt Center, the McGraws found another facility at Duke Medical Center, with Tim giving the go-ahead for the $5,800-per-month experimental drug. He also bought a motor home for Tug, his brother and two friends to drive across the country.

His health failing, Tug requested to spend his final days at Tim’s cabin outside Nashville. He died there on January 5, 2004, alongside his son with the rest of his family. Tim’s presence was a testament to his own persistence in reaching out to an indifferent father for all those years, as well as to the genuine bond that developed between the two men despite the rough beginnings that could easily have torpedoed any hope of redemption.

Thank you for reading this post Tim McGraw Didn’t Meet His Dad Tug Until He Was 11. Inside Their Complicated Relationship at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: