You are viewing the article The Unlikely Marriage of Alexander Hamilton and His Wife, Eliza at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Alexander Hamilton and his wife, Eliza Schuyler, were an unlikely couple whose marriage defied societal norms and expectations. Born into different worlds, they came together in a union filled with love, passion, and resilience. Their story is one of two individuals from contrasting backgrounds, joining forces to create a lasting partnership that would shape not only their personal lives but also the course of American history. As we delve into the details of their uncommon marriage, we uncover the many layers of their relationship, the challenges they faced, and the profound impact they had on each other’s lives. Through their shared journey, we gain a deeper understanding of the complexities of love, devotion, and the enduring power of a seemingly unlikely union.

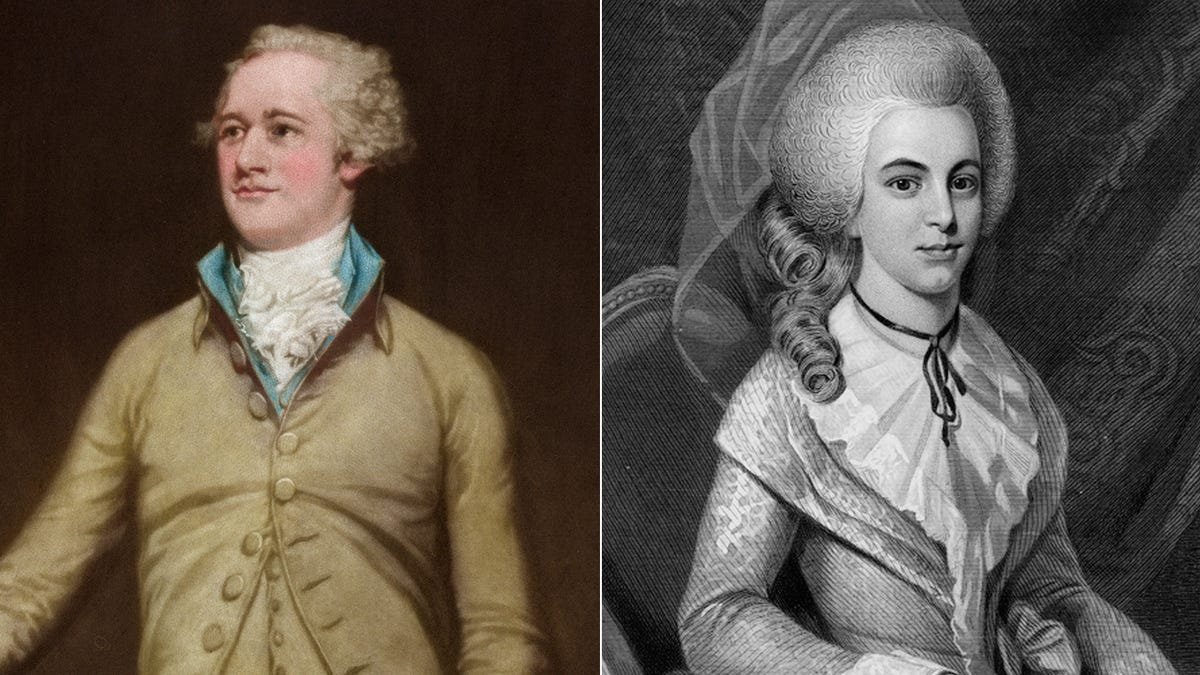

When Elizabeth “Eliza” Schuyler married Alexander Hamilton in December 1780, the pair would have seemed like a great mismatch on paper. She was rich, he was poor. She came from a well-established, highly-regarded family, he was an orphaned immigrant. But despite these differences, the pair formed a lasting bond that has been the subject of numerous books and the award-winning musical, Hamilton.

Eliza descended from some of America’s most prominent early families

Born in August 1757, she was one of eight surviving children of Philip Schuyler and Catherine Van Rensselaer. Catherine, also known as Kitty, was the daughter of one of New York State’s oldest, richest and most prominent Dutch families. A noted beauty, she was a bright star on the social scene of Albany before and after her marriage.

Philip also hailed from a prominent family and he commanded a militia during the French and Indian War of the 1750s. He eventually became a prominent landowner, with tens of thousands of acres in the Albany area. He served several stints in the Continental Congress and was involved in planning a number of notable Revolutionary War battles, including the surprising Colonial victory at Saratoga in 1777, the first widespread British defeat and a turning point of the war. After the war he was active in both local and national politics, even serving as a U.S. senator from New York from 1789 to 1791 — losing his seat to none other than Aaron Burr (who would eventually kill his future son-in-law Alexander in a duel).

Eliza had pedigree, money and status while Hamilton had none

Hamilton’s prospects were far less promising. He was born c. 1755 on the island of Nevis, in the British West Indies. His mother, Rachel Faucette, had been born there to British and French Huguenot parents. He was born out of wedlock, a status that his political opponents would later seize on. Because his mother had never divorced her first husband, Hamilton’s father, James, abandoned the family, likely to prevent Rachel from being charged with bigamy. A single mother, Rachel struggled to provide for Alexander and his brother before she died in 1768, leaving him an orphan.

But while Hamilton came from an impoverished background, he had two key traits that would help propel him to the top — intelligence and ambition. He found work at a local import-export firm, where he quickly impressed his bosses. A lifelong reader who was largely self-educated, he soon set his sights far beyond his tiny island home. In 1772, after writing a powerful essay describing the devastation inflicted on Nevis by a recent hurricane, a group of local businessmen took up a collection to send young Hamilton to America to continue his education.

Hamilton and Eliza came of age on the eve of a Revolution

Hamilton attended King’s College, now Columbia University, and dived headfirst into the political debate and heady atmosphere that was pre-war New York City. Just a teenager, he made a name for himself writing pamphlets and articles supporting the Revolutionary cause. But while his brilliance was apparent to those who met him, Hamilton was eager to prove himself on the field, not just with the pen. In the early months of the war, he formed an artillery company and later served at the battles of White Plains, Trenton and Princeton. By early 1777, he’d made enough of a name for himself that several Colonial generals asked him to join their staffs. Still eager to find glory in battle, he turned them all down. But when George Washington asked him to become his aide-de-camp, Hamilton embarked on what was, arguably, the second most important relationship of his life. The two became extremely close. The orphaned immigrant had found a father figure, and Hamilton became like a son to the future president.

Thanks to her father’s role in the war and her family’s social status, these years were a time of excitement for Eliza as well. Largely educated at home, she was bright and good-natured. Attractive, if not beautiful. Prominent military and political figures made frequent visits to the Schuyler homes, including a young officer named Alexander Hamilton, who briefly stayed with the family while traveling through Albany.

Despite their differences, the pair quickly bonded

Some two years after their brief meeting in Albany, Eliza and Hamilton met again at a party given for Washington’s staff by Eliza’s aunt in the winter of 1780, near Morristown, New Jersey. Hamilton was surely aware of Eliza’s wealth and connections, which likely played a role in his initial attraction to her. And Eliza knew enough about his impoverished background to give cause for concern. But she was immediately smitten with the brilliant, charming young man, and the two quickly started up a correspondence.

Eliza’s initial fears that her family would disapprove of the relationship were soon eased. The entire Schuyler family seemed as taken with Hamilton as she was. Oldest sister Angelica formed a deep friendship with Hamilton, and the two would exchange political and personal advice until Hamilton’s death. Philip Schuyler shared similar politics with Hamilton, and, like Eliza and others, realized that Hamilton’s star was on the rise — thanks in no small part to his role at Washington’s side.

Their married life was tumultuous

Unlike two of Eliza’s sisters (including Angelica) who had eloped due to family doubts about their husbands, Eliza received her father’s blessing. On December 14, 1780, the couple wed at the family home in Albany.

Theirs would be a loving marriage, though not without heartbreak and pain. They would raise a large family but see their eldest son killed in a duel while defending his father’s honor. Hamilton would reach the heights of government and power but be tripped up by his own arrogance, ambition and hubris. Eliza would weather a storm of pain and embarrassment following very public revelations of Hamilton’s adultery.

But she remained steadfastly loyal to him, and after his death in 1804, it was Eliza who would ensure Hamilton’s contributions to the founding of America were never left out of the history books. She died aged 97, in 1854.

In conclusion, the marriage between Alexander Hamilton and his wife, Eliza, was indeed an unlikely union. Despite their contrasting backgrounds and the challenges they faced throughout their relationship, they were able to build a strong and enduring bond. Alexander, an ambitious and intellectual statesman, found in Eliza a loyal and supportive partner who played an essential role in his personal and political life. Eliza, on the other hand, defied societal expectations by standing by her husband’s side through political scandals and personal tragedies. Together, their love and partnership not only sustained them through their own struggles but also contributed to the shaping of American history. The unlikely marriage of Alexander Hamilton and Eliza serves as a reminder that true love and compatibility can transcend differences in background, social status, and adversity. Their story exemplifies the power of love and resilience in overcoming the odds and leaving a lasting impact on both their own lives and the history of a nation.

Thank you for reading this post The Unlikely Marriage of Alexander Hamilton and His Wife, Eliza at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. How did Alexander Hamilton and Eliza meet?

2. What were the circumstances of Alexander Hamilton and Eliza’s marriage?

3. What was the age difference between Alexander Hamilton and Eliza?

4. Were Alexander Hamilton and Eliza’s parents supportive of their marriage?

5. Did Alexander Hamilton and Eliza face any challenges in their marriage?

6. How did Eliza handle Alexander Hamilton’s infidelity?

7. What role did Eliza play in Alexander Hamilton’s political career?

8. How did Alexander Hamilton and Eliza’s marriage influence their children?

9. Did Alexander Hamilton and Eliza have a happy marriage?

10. What was the impact of Eliza’s death on Alexander Hamilton?