You are viewing the article The Unlikely Friendship of Mark Twain and Ulysses S. Grant at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

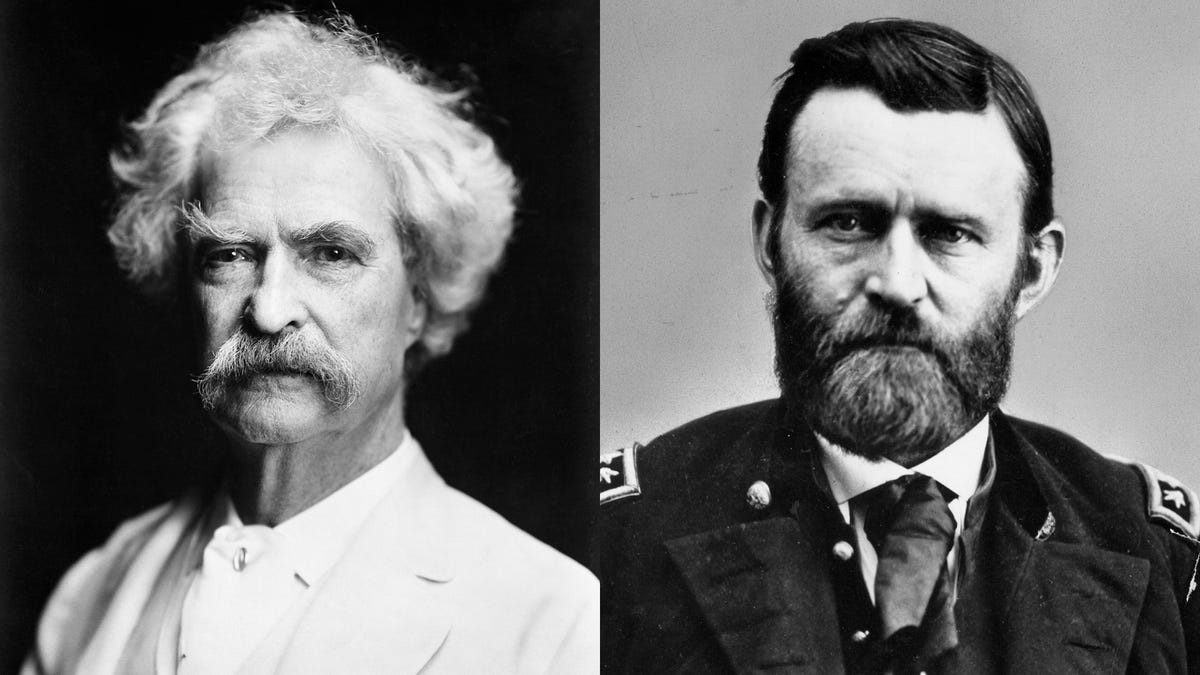

Two of the most famous Americans of the 19 century, Mark Twain and Ulysses S. Grant’s formed a surprising friendship. On paper, the outgoing, personable author and the quiet, reserved general-turned-president couldn’t be more different, but their close bond led to the publication of a landmark work of autobiography — with both men racing against the clock as Grant neared death.

The two first met years before Twain was famous

Like many other Americans, Twain had long admired Grant. They were both from the Midwest – Grant from Ohio and Twain from Missouri. And both had endured difficult early careers (Grant had once named a soon-to-fail farm “Hardscrabble”). Grant’s success as a general during the American Civil War had captured the North’s attention, and Twain reportedly carried a copy of Grant’s infamous letter to Confederate General Simon Buckner during the Battle of Fort Donelson in his wallet as a keepsake.

But their first meetings hardly portended the friendship that was to follow. In 1867, Twain, still an unknown journalist, traveled to Washington D.C., to act as private secretary to a Nevada senator. In December of that year, he briefly met Grant, then still in the U.S. Army, at a party. After leaving his position, Twain returned to D.C. to lobby for the passage of a bill in 1870. His first book had recently been published, but he was not yet a household name, and when his former boss brought him to the White House to meet now-President Grant, Twain recognized the power imbalance between the two, later writing to his wife about the encounter: “I shook hands and then there was a pause and silence. I couldn’t think of anything to say. So I merely looked into the General’s grim, immovable countenance a moment or two, in silence, and then I said: ‘Mr. President, I am embarrassed – are you?’”

READ MORE: How Ulysses S. Grant Earned the Nickname “Unconditional Surrender Grant”

They grew closer after Twain roasted Grant at a celebratory dinner

Following that inauspicious White House meeting, their paths didn’t cross again for almost a decade. In November 1879, Twain was invited to a dinner in Grant’s honor in Chicago. After the meal, a series of speakers rained endless praise on Grant well into the night. Twain, the evening’s final speaker, didn’t take the floor until well after midnight. Rather than follow suit with an obsequious toast to Grant’s talents, Twain proceeded to poke fun at the esteemed guest of honor.

Fearful that he had offended Grant, Twain waited for a reaction. The group of men seemed shocked, but not Grant. He was the first to laugh, and when he was re-introduced to Twain at the end of the night, Grant clearly recalled their first meeting, responding, “Mr. Clemens, I am not embarrassed, are you?” The two quickly became close friends.

Their friendship developed during the most difficult periods of Grant’s life

After leaving office in early 1877, Grant, not yet 60, was restless. He and his wife, Julia, took an extended worldwide vacation which left them financially taxed. An unsuccessful run at the Republican presidential nomination in 1880 further dampened his spirits. Grant had never been a good businessman and had experienced a number of financial failures before his military rise during the Civil War. Ever anxious to provide for his family, in 1881 he agreed to join his son Ulysses S. Grant Jr, nicknamed “Buck,” in his investment company, Grant and Ward.

Buck’s partner was a young, ingratiating financier named Ferdinand Ward, perceived to be so talented that he had earned the nickname the “Napoleon of finance.” Ward and the elder Grant quickly bonded, and Grant had soon invested the bulk of his money in the firm, taking an office in their New York headquarters. Grant family members, as well as other prominent figures of the time, including artist Thomas Nast, followed his lead, and money soon poured into Grant and Ward’s coffers.

But Ward’s outer charm hid a dark secret. The company was little more than a Ponzi scheme, with Ward pocketing the capital while paying out dividends. He was able to keep up the pretense for several years, but an economic downturn worsened the company’s financial state. Grant was forced to borrow $150,000 from friend William Henry Vanderbilt to prop up the company. But in 1884 Ward’s embezzlement was exposed and the company collapsed.

Ward was eventually sentenced to 10 years in prison for his role. But the Grant family was financially ruined, forcing them to curtail the lavish lifestyle Ward’s trickery had funded. Although neither Grant was aware of the swindle scheme, the elder Grant was once again faced with the prospect of poverty.

Twain came to Grant’s rescue during his time of need

Twain was by now a regular visitor to Grant’s New York home and saw his friend’s distress firsthand. Several years earlier he had suggested that Grant write his memoirs, but Grant had demurred, convinced he was no writer.

Twain wasn’t the only one who wanted Grant to write his autobiography. The editors of Century Magazine, one of America’s most-read journals, asked Grant to write a series of articles on the Civil War battles that had bought him fame. With no other source of income on the horizon, he reluctantly agreed, working out of the New Jersey home he and Julia were temporarily forced to move to due to lack of funds. His first articles were terse and unexciting. But he quickly improved, discovering a literary talent that few would have expected. The editors asked Grant to expand the articles into a memoir, but he remained reluctant.

But yet another blow forced Grant to reconsider. Just months after the collapse of Grant and Ward, Grant’s health worsened. After ignoring lingering throat pain for months, he was finally diagnosed with cancer, likely caused by his decades-long, constant cigar smoking. The diagnosis was a death sentence, and a despondent Grant was now left to worry about the future financial prospects of his beloved wife. Grant told the Century editors that he would write the book after all. They offered him a standard 10 percent royalty on expected sales, and a contract was prepared.

When Twain learned of the deal, he was appalled at the low sum they had offered Grant. Twain and Grant may have had very different personalities, but they both had experience as bad businessmen. Like Grant, Twain had gone into business with a family member, starting a publishing company Charles L. Webster and Company with a nephew. Despite Twain’s literary fame, the business was on the brink of collapse. Twain now saw an opportunity to help his friend — and himself.

He offered Grant a remarkably generous contract, including 70 percent of any possible royalties, an upfront advance and living expenses. The ever-loyal Grant was initially reluctant to renege on his deal with the Century and worried about the effects on his friendship with Twain if the book was a failure. But he finally agreed to Twain’s terms.

Twain developed an ingenious marketing campaign for Grant’s book

Despite constant pain that often left him unable to eat, drink or even sleep, Grant spent hours each day working on the book. Wrapped in layers of clothing to keep his rapidly-shrinking frame warm, he churned out page after page, all while newspaper headlines blared the latest updates about his impending death.

While Grant raced to finish the book, Twain set about promoting it. The book would be sold as a subscription of two volumes. Capitalizing on Grant’s continued popularity in the North, he recruited a 10,000-strong sales team. Comprised primarily of former Union soldiers (many dressed in their old uniforms), the agents traveled from door-to-door, using a 37-page sales pitch Twain himself wrote.

Early sales predictions were promising, providing Grant with the mental fortitude to continue. Tucked away in a home in the more welcoming climate of the Adirondack Mountains, he was eventually forced to dictate some of the memoir to an assistant when he was unable to write. Twain was a frequent visitor, consoling his friend and revising the manuscript with Grant, sometimes passing notes back and forth when Grant was eventually unable to even speak.

Grant’s memoirs were a runaway success

Grant finally finished the 336,000-word manuscript in mid-July 1885. He died a week later, aged 63. More than 1.5 million people attended his funeral in New York City.

The first volume of the memoirs was published later that year and was an overnight sensation. Still considered one of the finest military autobiographies ever written, it exceeded all expectations. Thanks to Twain’s ingenious idea to include what appeared to be a handwritten note from Grant in each book, the first run of 350,000 quickly sold out.

Julia would eventually earn some $450,000 (more than $11 million in today’s money) from sales of the book. Grant had feared he would leave her penniless, instead, Twain’s deal made her one of America’s richest women.

But Twain’s generous support for a dying friend didn’t help him in the long run. Despite earning millions publishing both Grant’s memoirs and Twain’s own Huckleberry Finn, Charles L. Webster and Company proved unsuccessful. Although Twain wound later bounce back and become rich once again later in life, his publishing company went bankrupt less than 10 years after Grant’s death.

Thank you for reading this post The Unlikely Friendship of Mark Twain and Ulysses S. Grant at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: