You are viewing the article The Secret Relationship That Charles Dickens Tried to Hide at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

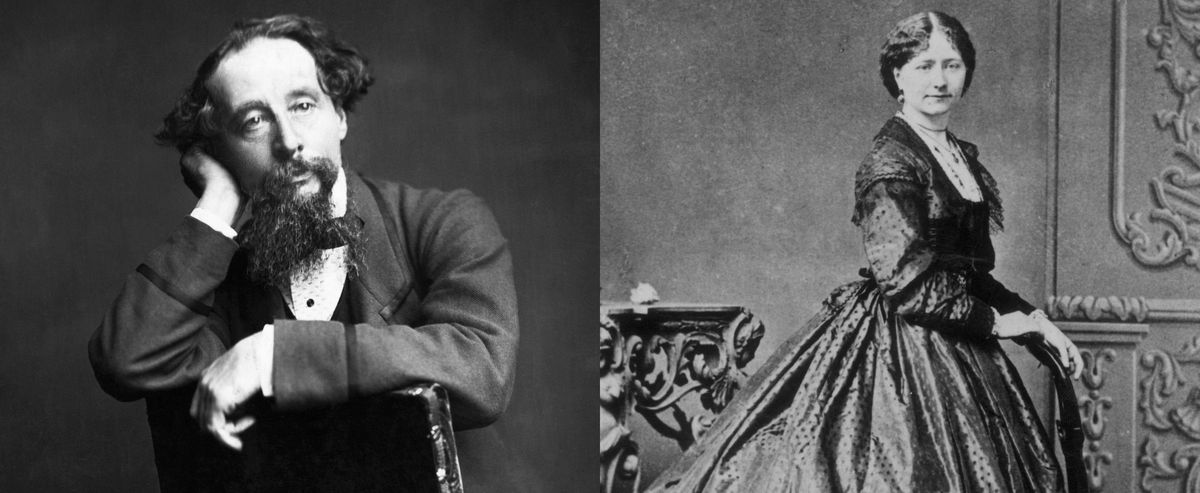

By 1857, when Charles Dickens met the young actress Ellen Ternan, he had been one of England’s most famous men for the past two decades.

To his legions of fans, who gobbled up best-selling serialized novels like The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and A Christmas Carol, Dickens seemed like the ultimate Victorian-era family man. Born poor, he had lifted himself up through hard work and was living out his professed ideals of domesticity and moral rectitude with his wife, Catherine, and their large brood of children.

But the truth, as always, turned out to be more complicated. Within a year, Dickens’ infatuation with the then-18-year-old Ternan — known as Nelly — would lead to the messy breakup of his marriage, and launch a relationship that would last the remainder of his life.

Dickens first met Ternan when he cast her in a play

Indulging his lifelong passion for theater and acting, Dickens was appearing in an amateur production of his friend Wilkie Collins’ play The Frozen Deep during that summer of 1857, when he decided to enlist professional actresses to take on the roles previously played by his friends and family. Through a theater friend, he hired Mrs. Fanny Ternan (née Jarman), who had been an acclaimed leading lady in England, Ireland, Scotland, and the United States in her younger days, and two of her three daughters, Maria and Nelly, to appear in the production.

Nelly had acted since was a child, but always in the shadow of her oldest sister, Fanny, who had been considered a prodigy. In her book The Invisible Woman, Claire Tomalin described the blonde, blue-eyed Nelly as she appeared at the time, just a few months before she met Dickens: “Everything about her signaled innocence and vulnerability. In her neat little dresses and ringlets, she could have stepped out of a fairy story.”

READ MORE: Charles Dickens Wrote A Christmas Carol in Only Six Weeks

He had a nasty breakup with his wife

By the mid-1850s, Dickens seems to have already been unhappy in his marriage, according to letters he wrote at the time. In 1855, he began writing to his first love, Maria Beadnell, whom he had courted unsuccessfully before meeting his wife, Catherine. But when the two met in person, she failed to live up to his romantic memories; he later wrote to an admirer that she had grown “extremely fat.”

After he met Nelly, things deteriorated quickly between Dickens and Catherine. They separated in May 1858, and Catherine moved out of both of the family’s houses. Dickens even used his paternal right to sole custody to cut off contact between her and their younger children. Catherine’s younger sister Georgina Hogarth, who had long lived with the family, took Dickens’ side, claiming that Catherine had neglected her own children.

As rumors flew that Dickens had left his wife for a younger woman (or even an incestuous love affair with Georgina), the novelist attempted some damage control. “Some domestic trouble of mine, of long-standing, on which I will make no further remark than that it claims to be respected, as being of a sacredly private nature, has lately been brought to an arrangement,” Dickens wrote in a statement published in the Times. “By some means…this trouble has been made the occasion of misrepresentations, most grossly false, most monstrous, and most cruel.”

In 2012, a long-lost letter surfaced that confirmed Dickens’ attitude toward Catherine at the end of their marriage, as well as his eagerness to get out of the situation and move on. In it, he instructs his lawyer to provide Catherine with £600 per year, or the equivalent of some £25,000 today. As biographer Michael Slater told the Telegraph at the time, “The tone of [the letter] is a man just desperate to get this separation business finished at almost any price and as fast as possible. It was generating bad publicity for him and he clearly found the marriage intolerable.”

Dickens and Teran had a 13-year relationship

Much of the gossip surrounding his marriage drama soon died down, thanks to Dickens’ determined efforts to hide Nelly’s growing importance in his life. In 1859, she moved into a London townhouse bought in her sisters’ names, presumably by Dickens. Nelly soon retired from acting and would remain largely isolated, aside from her mother and sisters, for the length of her relationship with Dickens. (Her father, also an actor, had died in an insane asylum when Nelly was young, possibly leaving her with a need for a father figure that Dickens, then in his mid-40s, fulfilled.)

As Dickens continued his prolific writing career in the 1860s, including his novels A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend, Nelly disappeared almost completely from view for several years. According to Tomalin, the evidence suggests she lived in France during this period, and may even have given birth to a child around 1862 to 1863, but that child died in infancy.

When she returned to England after 1865, Dickens installed Nelly in Slough, a town outside London, and saw her frequently between work and time at his family home in Gad’s Hill. Historians have pieced together clues to his complicated comings-and-goings from a pocket diary kept by Dickens for much of 1867 that was lost during his tour of the United States later that year.

Dickens’ veiled references to personal unhappiness in his correspondence near the end of his life led Tomalin to speculate that Nelly was unsatisfied with her life as the much-younger, secret mistress of the great man, even as she might have been financially (and otherwise) dependent upon him. Even if this was so, they remained attached until Dickens died in 1870, at the age of 58.

Even after Dickens’ death, his affair was kept a secret

Georgina became the chief protector of her brother-in-law’s legacy and took care to keep his secret. It helped that Nelly launched a new life after Dickens’ death, shaving more than a decade off her age and marrying a much younger man, George Wharton Robinson, with whom she had two children.

Nelly and Dickens apparently destroyed all correspondence between them, and though rumors resurfaced in the 1890s, more definitive evidence of their relationship didn’t come out until long after her death in 1914. Dickens’ daughter Katey confided the truth about her parents’ separation to a friend, Gladys Storey, who published her book Dickens and Daughter in 1939 after Katey and all of Dickens’ children had died.

Even as more historians and biographers investigated the relationship between Dickens and Nelly Ternan in the 1950s and beyond, others continued to argue that it was platonic, or merely an infatuation on Dickens’ part. But with the publication of Tomalin’s 1990 book and its film adaptation, released in 2013, Nelly Ternan’s story has grabbed the spotlight again, revealing the real woman at the heart of a Victorian icon’s scandalous private life.

Thank you for reading this post The Secret Relationship That Charles Dickens Tried to Hide at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: