You are viewing the article The Richard and Mildred Loving Story at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

The Richard and Mildred Loving Story is a profound and inspiring tale that delves into the heart of one of the most significant civil rights cases in America’s history. It follows the lives of Richard Loving, a white construction worker, and Mildred Jeter, a woman of African American and Native American descent, as they navigate the complexities of their interracial relationship in Virginia during the 1950s. Their love for each other became the catalyst for a legal battle that ultimately challenged and dismantled the deeply rooted laws against interracial marriage in the United States. This poignant story sheds light on the injustice and discrimination faced by interracial couples, while also highlighting the power of love, resilience, and the pursuit of justice in the face of adversity. Through the lens of the Loving couple, we gain a profound understanding of the enduring legacy they left behind, forever changing the landscape of civil rights and marriage equality in America.

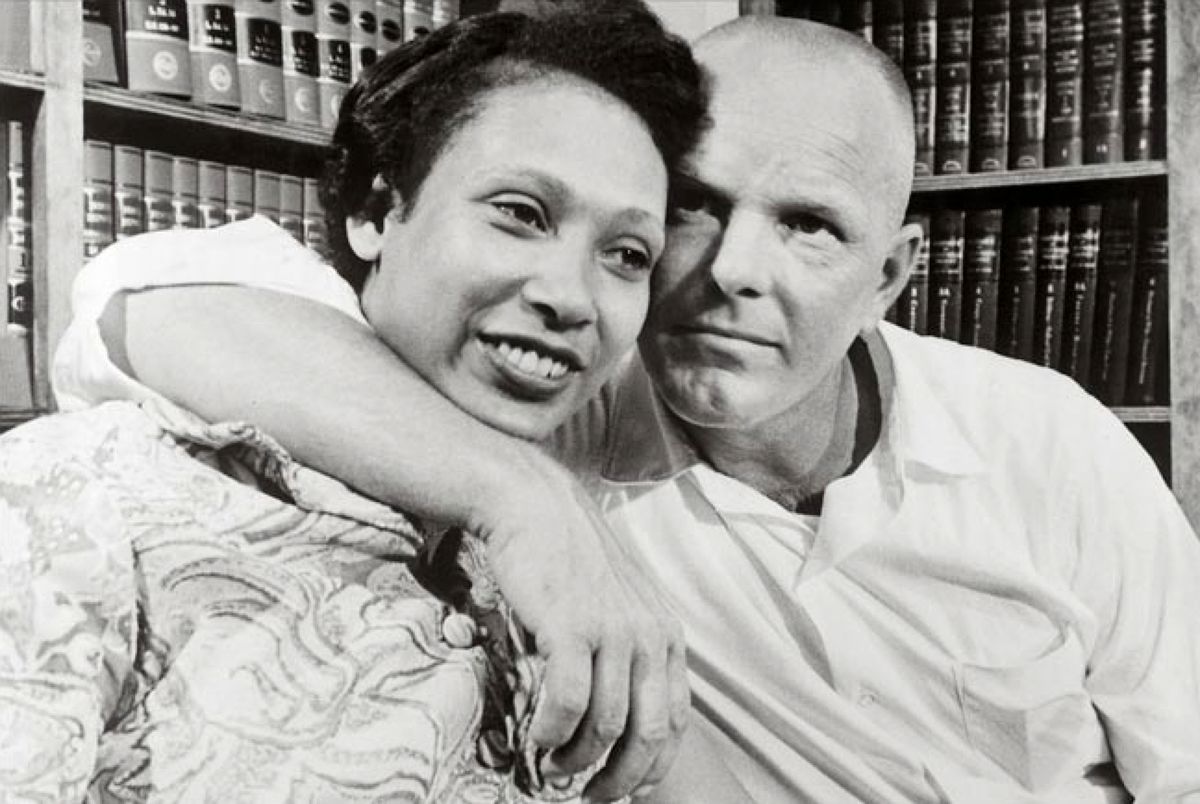

To say that Richard and Mildred Loving were reluctant heroes would be an understatement. Richard, with his platinum blonde crew cut, backwoods accent and taciturn ways, looked more like a caricature for a white supremacist. And then there was Mildred. A soft-spoken, shy woman of African and Native-American descent, she possessed a quiet charm but like her husband, had no desire to bring attention to herself.

But the attention would come, and it would change the course of American history.

The couple had to flee Virginia to avoid prison time

In 1958, the couple was jolted out of their bed in the middle of the night and arrested by local Virginia police. Their crime: violating the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which forbid interracial marriage. Although the Lovings were legally married in Washington, D.C., the state of Virginia, which the couple made their home in, was one of more than 20 states that made marriage between the races a crime.

A local judge allowed the Lovings to flee the state to avoid prison time. The couple decidedly moved to D.C., just two hours away from Virginia, but for the two of them, their whole world — along with their family and friends — was wrapped up in their tiny farming community of Central Point, Virginia. They were simple people who wanted to live a simple life, and they were determined to go back home. After living the next five years in exile and raising their three children, Mildred found an opening.

The Lovings’ case went to the Supreme Court

Feeling empowered by the Civil Rights Movement, Mildred wrote to Robert F. Kennedy in 1963 asking for counsel. Kennedy referred her to the ACLU, and it was there that their case eventually went to the Supreme Court. The judges unanimously ruled in favor of the Lovings with Chief Justice Earl Warren writing “the freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.”

The historic ruling led to the overturning of similar statutes in more than a dozen states and ultimately marked the end of segregation laws in America. But for the Lovings, the ruling was simply the freedom to go home and to continue on with their lives, this time, loving without fear.

Although Richard died in 1975 following a car accident, Mildred was able to live long enough to offer her support for gay marriage. On the 40th anniversary of the Lovings’ landmark case and a year before her death in 2008, she said in a public statement: “The older generation’s fears and prejudices have given way, and today’s young people realize that if someone loves someone, they have a right to marry.”

To look at the Lovings’ legacy (along with their improbable last name), they make the saying “love conquers all” that much more believable.

In conclusion, the Richard and Mildred Loving story is a powerful reminder of the enduring struggle for equality and justice in America. Their fight to legalize interracial marriage not only challenged discriminatory laws and societal prejudice, but it also paved the way for the recognition of love and marriage as fundamental human rights. The Lovings’ journey from a small Virginia town to the Supreme Court not only changed the lives of countless interracial couples but also shaped the legal landscape of the nation. Their unwavering determination to live as husband and wife, despite the immense challenges they faced, serves as an inspiration for all who believe in the power of love to overcome adversity. Their story continues to resonate and reminds us that love knows no boundaries, and that every individual deserves the right to marry the person they love. The legacy of the Lovings shall forever stand as a testament to the relentless pursuit of equality and the triumph of love.

Thank you for reading this post The Richard and Mildred Loving Story at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. Richard and Mildred Loving: The True Story behind the Historic Supreme Court Case

2. Interracial Marriage Laws in the United States during the 1960s

3. Loving v. Virginia: The Landmark Civil Rights Case that Legalized Interracial Marriage

4. The Love Story of Richard and Mildred Loving: A Tale of Romance and Resistance

5. Richard and Mildred Loving: Breaking Barriers and Challenging Social Norms

6. The Impact of the Loving Case on Civil Rights and Marriage Equality

7. Historical Background of Racial Segregation and Anti-Miscegenation Laws in America

8. Documentary Films and Books about the Richard and Mildred Loving Story

9. The Legacy of Richard and Mildred Loving: Pioneers of Love and Equality

10. The Loving Story: Exploring the Lives of Richard and Mildred Loving