You are viewing the article The Real Story of South Florida Rapper XXXTentacion at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

or…

Click this link to read “XXXTentacion: An Annotated Timeline of Miami New Times Coverage”

Editor’s note, November 1, 2022: In late May of 2018, Miami New Times intern Tarpley Hitt pulled off a journalistic coup: She walked up to the posh, Tuscan-style residence of Miami hip-hop star XXXTentacion, knocked on the door, and talked her way inside, where the uncharacteristically candid rapper (real name Jahseh Dwayne Onfroy) consented to an interview.

Published on June 5, Hitt’s profile set off a seismic wave that rumbled across the U.S. pop-culture landscape. XXXTentacion’s fans and detractors alike were aware of the heinous and widely publicized domestic-abuse charges that had Onfroy confined to his Parkland manse under house arrest, but Hitt’s story laid them bare in the context of a troubled childhood which was itself marked by a litany of horrifyingly violent offenses — often described or addressed by Onfroy in his own words.

Even more stunning: Hitt also managed to score an interview with the young woman prosecutors claimed was the victim of Onfroy’s alleged abuse. The woman, 22-year-old Geneva Ayala, had mostly eluded the media spotlight but agreed to talk on the record with Hitt.

As it turned out, Hitt’s story contained XXXTentacion’s last public comments about his predicament and the path that had led him there. Thirteen days after New Times published the profile, Onfroy was shot to death in broad daylight at a Broward County motorcycle dealership in an apparent robbery gone wrong.

Jahseh Onfroy died instantly, but the grim final tableau guaranteed XXXTentacion perpetual notoriety. In the ensuing years, even as his four alleged assailants continue to await trial, the rapper’s rise and fall inspired a biography and a Hulu documentary.

Those versions of Jahseh Onfroy’s life were composed with the benefit of hindsight, but also its burden. Neither was able to duplicate the feat pulled off by a New Times intern in the spring of 2018.

Tarpley Hitt’s feature, “The Real Story of Rapper XXXTentacion,” is below:

One: XXXTentacion Answers the Door

The corner house on a rich but unremarkable street in Parkland, about four miles from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, belongs to a scrawny 20-year-old with a tree tattoo in the middle of his forehead. He stands about five feet six inches tall and weighs 125 pounds with shoes on. The kid bought the house in November, moved in shortly after, and made the place his own, decorating in the sparse, halfhearted way you’d expect from a teen homeowner but with occasional high-end touches, like an industry-grade recording studio on the first floor.

Today two cars — a black BMW and a colossal van — are parked out front in one of those circular driveways that are popular in the suburbs. A team of landscapers dots the edges of the property, ensuring the shrubs stay pruned. There are a half-dozen Wi-Fi networks to choose from, all named variants of “Theworldwithin.”

The $1.4 million Tuscan-style home has no doorbell, but a rotating cast of kids routinely answers knocks on the door. Around noon on a recent Thursday, it’s a blond boy with a peach-fuzz mustache and a cursive face tattoo. When the owner is requested, Peach Fuzz grumbles something inaudible and disappears behind the wooden door. He returns trailing his five-foot-six friend, who is shirtless, barefoot, and a little angry.

In real life, the homeowner is strikingly pretty, with huge irises and a jolt of blue hair pulled into two french braids. He’s covered in tattoos: Most prominent are an elephant head on his throat, “17” on his temple, and “Cleopatra,” his mother’s name, scrawled on his chest. He is charismatic, quick to laugh, and slightly condescending. When a visitor, who found the place from a stray speeding ticket, says she’s surprised he came outside, he says, “The word would be ‘dumbfounded.’”

In the past six months, this guy has rarely left his house. That’s partly because he was working on an album that, when it dropped this past March 16, debuted at number one on the Billboard 200. But it’s mostly due to the fact he’s on what his lawyer calls “modified house arrest” while awaiting trial for a disturbing list of criminal charges, including domestic battery by strangulation, false imprisonment, and aggravated battery of a pregnant woman.

He denies the charges, saying in a September 2017 Instagram video: “Everybody that called me a domestic abuser, I’m going to domestically abuse y’all little sisters’ pussy from the back.”

“I’m going to domestically abuse y’all little sisters’ p**** from the back.”

tweet this

But today, after some back-and-forth, the homeowner — whose real name is Jahseh Dwayne Onfroy but whom the world knows as the polarizing SoundCloud artist XXXTentacion — lets the door swing open and leads the way to his blue-lit studio. “Take off your shoes,” he says.

For the next two hours, Onfroy sits cross-legged on a comfy chair and talks openly about astral projection (he’s for it), feminism (he’s against it), and systemic oppression (it’s over, apparently) while declining to address or reflect upon the criminal reasons he’s unable to leave his house. “Would I change anything about my journey?” he says at one point. “Fuck, no.”

The controversial rapper emerged onto the public stage in early 2017, when a single he uploaded to SoundCloud burst out of underground music circles and into the mainstream. The track was short, distorted like most of his songs, and named an imperative “Look at Me!” But as listeners and media took his instruction to heart, they uncovered details about Onfroy’s past, including the brutal allegations of domestic abuse.

When the claims surfaced, the singer joined a lineup of controversial male figures, from Chris Brown to Harvey Weinstein, whose accusations of abuse have spurred a national conversation about an age-old question: Can great art be separated from problematic artists? But unlike Brown, Weinstein, or many of their peers, whose work was well known before it became controversial, Onfroy’s celebrity and extreme criminal charges are closely tied. As the singer’s friend and fellow rapper Denzel Curry once said in an interview with HotNewHipHop: “The thing with X is, when he got into trouble, that’s what blew him up.”

In many ways, Onfroy’s continued commercial viability is a testament to what accused assailants can still get away within the court of public opinion, especially when their victims — like Onfroy’s — are low-income and women of color.

But after a review of hundreds of pages of court documents, a two-hour talk with the singer, and interviews with his alleged victim, old friends, collaborators, fans, and foes, what emerges is not a portrait of a supervillain. Instead, it’s a grim picture of a banal, unglamorous, half-likable kind of figure whom women around the world encounter every day — someone who isn’t profoundly addled as much as pathetically insecure, obsessed with power, and incapable of following one essential directive of human conduct: “It’s so simple,” his accuser says. “Just don’t hit anybody.”

Two: Violence Begets Violence Begets… Performance

Once, when Onfroy attended the beige strip of concrete buildings called Margate Middle School, a classmate had a crush on him. In the idiom of preteen infatuation, she showed it by hitting him. The boy asked his mother if he could hit back. Her answer: Give the girl three warnings; if she keeps hitting, you have to handle it.

Onfroy took those words to heart. When the girl next bothered him, he says, he “slapped the shit out of her and kneed her.”

His mom was surprised. “[She] realized how serious I took her,” Onfroy says. “Her word was my bond.”

Onfroy’s tumultuous but intensely close relationship with his mother, Cleopatra Bernard, was one of the defining aspects of his early life and tied to the pattern of fighting that characterized his adolescence. He didn’t live with her while growing up; she was 17 or 18 when she had him and in a hard spot financially. “Raising a kid was, honestly, one of her last priorities,” the singer says. He spent the first decade of his life cycling through the homes of friends, family, and babysitters.

“From what I can remember, I’ve never seen Jahseh living with [his mom],” his half-sister Ariana Onfroy, a recent Howard University graduate with a burgeoning YouTube presence, says in a video she posted in April. “He was always living with other people.”

Separation from his mother, whom Onfroy describes as “exactly like me, but probably more pretty,” affected him as a kid. When she was around, she’d buy him gifts: clothes from the prep staple Abercrombie & Fitch and the phones of the moment: first the Kyocera slide-up and then the Motorola Razr. When Bernard was gone, the void rattled Onfroy’s self-esteem. “My mom was the one who dressed me,” he told an interviewer in 2016. “My mom was the one who told me that I looked nice this morning or that I needed to go take a shower.”

Onfroy picked fights with other students to get his mother’s attention. “I chased her,” he says. “I used to beat kids at school just to get her to talk to me, yell at me.” After he was expelled from middle school for fighting, Bernard moved him to a residential program for troubled youth, Sheridan House Family Ministries, where he happily stayed for a few months. (“I’ve heard Jahseh is something of a rap star now,” says one administrator, who declined to give his name.) But after he turned 12, Onfroy most consistently lived with his grandmother, Collette Jones, in a Lauderhill gated community. “My grandma really feels like my mom,” he says. “My mom almost feels like more of a sister.”

“I used to beat kids at school just to get her to talk to me, yell at me.”

tweet this

Soon after starting school at Piper High in 2012, Onfroy graduated to more serious offenses, including armed robbery, burglary, possession of a firearm, resisting arrest, and possession of oxycodone, according to a 2016 interview with the underground hip-hop podcast No Jumper. He made it to his sophomore year at Piper before leaving for a stint in juvenile hall. Though short, still tatt-less, and with an “Iamsu! Afro” and a Wiz Khalifa-style patch of dyed hair, he established himself as one of the most volatile personalities in juvie, where he previewed an explosive, over-the-top machismo that would later become his brand.

In the No Jumper interview, he describes rooming with a gay inmate whom he repeatedly calls “a faggot.” He says he told a guard: “If he does anything I disapprove of, I’m gonna kill him.” After a week or two, when his cellmate “started staring,” Onfroy responded by placing the boy’s head on a concrete slab in the cell and stomping. “I was gonna kill him,” he says, “because of what he did, because I was naked. He was staring at me. I started strangling him.”

The boy screamed. “The guard hears him, and I’ve got his blood all over my hands, all of my chest, literally… I was going crazy. I smear his blood on my face, on my hands. I got it, like, in my nails. I got it all over me. I was going fucking crazy.”

The guards opened the cell and pulled Onfroy off. “I told you I would kill him,” the rapper reports saying. He contends the guards didn’t charge him. Instead, they told him to clean up. His mother was visiting, and when she spotted blood under his fingernails, she asked what had happened. When he responded, “This nigga did some gay shit, so I had to crack his head open,” she began crying.

Onfroy first told this story two years ago, but there are no records of the incident, and he declines to discuss it now. He says he’s moving away from that version of himself (“I’m like, really, really nice”).

After juvie, Onfroy ordered a snowball microphone on eBay and — along with a goofy, slow-moving kid named Stokeley Clevon Goulbourne, who would later become known by the stage name Ski Mask the Slump God — began making music. The pair started a collective called Members Only and began working on the beginnings of two mixtapes — Members Only Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 — which would come out the following year.

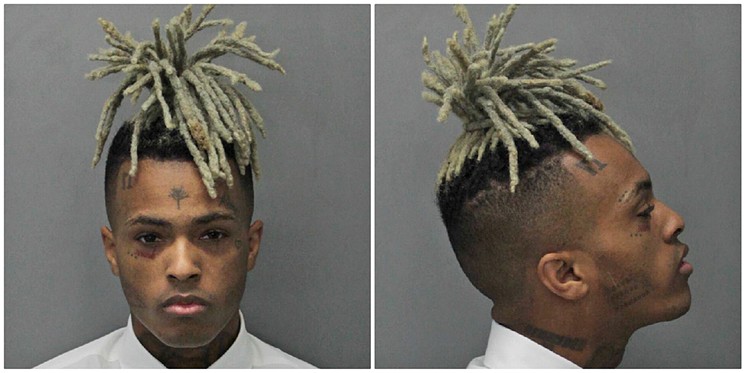

XXXTentacion posed for mug shots in 2017 after being charged with witness tampering.

Photos via Miami-Dade Corrections

In August 2014, for example, South Florida videographer Daniel Calle was booking a show of local acts at a venue in Hollywood, Florida. Calle, who has a hip-hop-Seth Rogan vibe, recalls Onfroy reached out to him and said he would perform.

“It was like, ‘My bad, dude, I can’t get you on this show,’” Calle recalls. “But he shows up anyway. He’s like, ‘I’m performing.’” Calle tried to stop him. Despite his size, Onfroy had a way of making things happen. “You have to understand,” Calle says, “he’s very sure. He’s very absolute.”

Three: Enter Geneva Ayala… and Abuse

In late May 2016, Onfroy was preparing to perform at an impromptu venue next to a thrift store in Oakland Park. As concertgoers crowded in, Onfroy spotted a girl from across the room. She had a model’s frame, dark eyeliner, inch-long acrylic nails, and a head of short, loose curls. Onfroy beelined for her. “He locked eyes with me,” the girl says. Then he grabbed her by the throat. “He made it seem sexy.”

The girl, Geneva Ayala, knew Onfroy a little and was about two years older. (She has rarely spoken to the media but agreed to talk on the record with New Times in part because #MeToo has changed the atmosphere for abuse survivors.) Although she hadn’t seen him in ages, they had been loosely flirting over social media for more than a year. “Me and you are going to be together before I’m famous,” he had once messaged her.

He was right. Two years later, after the pair had been dating for five months, Ayala would come forward and accuse Onfroy of the unrelenting, torturous domestic abuse that would send him to jail, to house arrest, and to jail again, then launch him meteorically into the spotlight.

Like Onfroy, Ayala had a chaotic home life. Her mother wasn’t interested in kids, she says; her father was busy with 13 others. At the age of 4, Ayala moved in with her grandmother in Miami, where she cycled through grade schools to escape bullying. At the age of 12, she returned to her mom. Though their relationship was rocky, Ayala didn’t want to leave: “You can almost be in love with your mother. That’s how I was.”

But when Ayala was 16 years old, her mother stopped paying for the electricity, then the water. At the end of the month, she ordered Ayala to move out. Her mother was pregnant, moving in with her boyfriend, and leaving her daughter behind. “She told her that they had a shelter in Homestead that she could go to,” one witness later recalled to state prosecutors, who would spend months investigating Ayala’s abuse claims.

After that, Ayala home-hopped. She stayed with neighbors for a while, occasionally at a motel her uncle owns in Hollywood, with her grandmother, and in parks when necessary. She worked overtime at a Pizza Hut to pay for food and incidentals.

When Ayala met Onfroy in November 2014, she had been living with her high-school boyfriend. Their relationship was strained. They fought often, and after a particularly bad argument, the boyfriend took to Twitter and posted an illicit picture of Ayala, exposing her without consent.

Onfroy, who saw the photo, messaged her and insisted on fighting the boyfriend. Ayala didn’t know Onfroy at all, but he was emphatic. “He was like, ‘Your boyfriend’s not supposed to be doing shit like this,’” she says. He set a date and time. The day of the fight, she met Onfroy with two friends at a Coral Springs movie theater, but her boyfriend never showed. The group hung out instead. Onfroy intimated that he liked Ayala and at one point pulled her onto his lap in a surprising but not off-putting way. “I liked him too,” she says. “I thought, He’s cute. He seems intelligent.”

When he dropped her off later that night, she forgot her phone in the car. She and Onfroy made arrangements to meet at a McDonald’s the next day, but the exchange soon slid into a hangout. “There’s a Vine from that day,” she says. “I’ve got the short, curly hair and he’s making weird noises, like Doodlebop noises.”

They spent the next three days hanging out constantly, walking around neighborhoods, taking the bus to far-flung stops, smoking cigarettes. One day it rained, so they stopped at the motel Ayala’s uncle owns and spent hours spilling their life stories. Onfroy bought her gifts — thoughtful ones, not the standard bracelet or teddy bear. “He got me a pillow,” Ayala says. A pillow? “Well, I didn’t have one.”

On the fourth day, the two separated and fell out of touch. They didn’t see each other for 18 months, until he grabbed her by the throat at his Oakland Park show. After that gesture, he held her for a moment and then disappeared. They saw each other briefly during the performance and hugged, Ayala remembers. He was sweaty.

Later, Onfroy invited her and a friend to an afterparty at the North Miami home of a hardcore porn star, Bruno Dickemz, who happened to moonlight as the singer’s manager. The girls agreed.

At the party, Onfroy and Ayala found themselves in a corner, catching up. Ayala was still living with her boyfriend, but their relationship had soured. On the spot, Onfroy offered to let her live with him. He said he liked her and had always pictured them together. She agreed to think about it. The next morning, she started packing.

Ayala moved into Dickemz’ house with Onfroy that day and almost immediately noticed something was off. According to her deposition and an interview, two weeks after moving in, Ayala admired a childhood friend’s new grills in a Snapchat video she posted. It prompted Onfroy to grab her iPhone 6S, smash it on the floor, and strike her hard in the face. He later fixed the phone, but Ayala was stunned. “I got slapped for no reason,” she says, “and he kept acting like everything was cool.”

“Stop believing the rumors. I did not beat that bitch; she got jumped.”

tweet this

Later that day, Ayala says, Onfroy hit her again. “I was really lightheaded, because the slap was so hard,” she recalls. “It was one of those slaps where you hear ringing.” She sat for a second in a daze. Onfroy told her to wait and then left the room. He returned holding a long-handled barbecue fork and a wire barbecue brush. “He was like, ‘Which one do you want me to use?’”

Ayala was confused. “Like, use for what?” In a deposition given seven months later, she recounts to a prosecutor: “He told me to pick between the two, because he was going to put one of them up my vagina.” She chose the fork. Then, Onfroy began pulling up her black-and-white striped dress. He lightly dragged the fork against the skin of her thigh. Ayala passed out.

“When I came to, I remember just thinking, I cannot let this happen to me,” she says. “This, right here, cannot happen to me.”

Ayala wanted to leave. But it was clear Onfroy wouldn’t “be comfortable” with that, she says in the deposition. She hadn’t broached the subject of leaving either because, according to the deposition, she “felt scared to be open with him.” When she did talk, he’d say she sounded stupid. “I barely spoke,” Ayala says.

So when Onfroy moved to Orlando in late June 2016, Ayala went with him. The depositions detail a pattern of regular, torturous abuse that summer, with daily verbal attacks and physical incidents every three or four days. According to Ayala’s statement, he beat her at times, choked her, broke clothes hangers on her legs, threatened to chop off her hair or cut out her tongue, pressed knives or scissors to her face, and held her head underwater in their bathroom while promising to drown her.

“His favorite thing was to just backhand my mouth,” Ayala says. “That always left welts inside my lips.” Onfroy would also try to guilt her with near-attempts at suicide, she says. He would fill a bathtub, dangle a microwave over the water, and threaten to let go.

Onfroy’s triggers were, in some ways, predictable — usually jealousy — but also erratic. Small things could set him off: like her humming another rapper’s verse or asking a friend what music he was playing.

“Once, we were all in the car, and my ex made a joke,” says Talyssa Lee, who was dating one of Onfroy’s producers in 2016. “[Ayala] just laughed as a reaction… When we got in the house, [Onfroy] walked into the other room and started beating on her.”

Lee, who didn’t know Ayala or Onfroy before the week of the car ride, noticed marks on Ayala’s body within hours of meeting her. “It was very clear that [Onfroy] was avoiding her face,” she says. “He was hitting her under the chin, on her back — her ribs were all bruised up.”

Almost as disturbing as the overt abuse, Lee says, was the lack of response from anyone around the pair. “All the boys around him, they witnessed that shit,” she says. “I can’t just sit here and hear a girl screaming in the next room… her voice gurgling because she’s being held underwater.”

On July 14, 2016, Onfroy was arrested in Orlando for allegedly stabbing his new manager, a guy nicknamed “Table,” who the singer claimed had been stealing from him. He bonded out only days later, but returned to jail in Broward County shortly after for earlier charges of armed home invasion and aggravated battery.

While Onfroy was in custody, Lee and a few other friends helped Ayala escape. Shortly thereafter, she moved to Texas, safely far from Onfroy.

But by August, the two were talking again. In September, when Onfroy was released on $50,000 bond and placed under house arrest, they decided to move in together. They found a place in Sweetwater: an apartment complex near Florida International University where three friends were living.

Soon, Onfroy learned she had been with someone else. Though they made up, the perceived transgression left Onfroy with a hysterical paranoia that she was hiding something, Ayala says.

On one occasion, he woke her in the middle of the night, took her outside where two of his friends were waiting, smashed a glass bottle, told her to tell him about the other man or he would “fuck [her] up,” and beat her while the others watched, according to her deposition. On another, he threatened suicide by dangling himself from a 12th-story balcony, holding onto the railing with only his legs.

These episodes could erupt out of nothing. When Onfroy wasn’t angry, Ayala says, they got along. They were trying to have a baby, and when a pregnancy test returned positive, Onfroy was happy, she says.

But the morning of October 6, 2016, while their roommates were out and Ayala was lying on Onfroy’s chest, he snapped. “He’s like, ‘You need to tell me the truth right now or I’ll kill you and this jit,’” Ayala says in her deposition, “the jit meaning child.”

For the next 15 minutes, she claims, Onfroy punched, slapped, elbowed, strangled, and head-butted her with unprecedented force.

When Ayala saw herself in the mirror, she says, her temples were swollen, her eyes were leaking, and she felt as if her head were “going to pop.” Around that time, she began to lose vision. She vomited. According to the deposition, Onfroy was still hitting her when their roommates walked in.

Ayala says she begged the onlookers to take her to the hospital. But Onfroy forbade it. The roommates placed tea bags on her eyes and antibiotic ointment on her cuts. Onfroy dressed her in a pink hoodie and sunglasses and drove her to North Miami, where he confiscated her phone and left her in Dickemz’ back room for two days.

The next morning, Sweetwater Police arrested Onfroy and later charged him with aggravated battery on a pregnant victim, domestic battery by strangulation, false imprisonment, and witness tampering. He pleaded not guilty and bonded out for $10,000 but was soon detained by Broward County officials for violating his house arrest.

Weeks later, Onfroy’s single “Look at Me!” which had been online for nearly a year, began to climb the charts.

Four: Introducing the Notorious XXXTentacion

It’s relatively rare that a song becomes popular years after its release. But when it happens, the track is usually buoyed by something else — maybe a movie or a commercial — that thrusts it into the public consciousness. For Louis Armstrong’s once-overlooked single “What a Wonderful World,” it was a feature in Good Morning Vietnam. For the Proclaimers’ “500 Miles,” it was the cult classic Benny & Joon. For Onfroy, it was likely his arrest.

The rapper had originally recorded “Look at Me!” in December 2015 with two South Florida producers, Jimmy Duval and a guy named Rojas who calls himself “The Underground DJ Khaled.” The song was posted to Rojas’ SoundCloud account, but received little reaction. The track was grainy and gleefully crude (“I’m like, bitch who is your mans/Can’t keep my dick in my pants”), with an earworm of a hook. It attracted a few diehard fans.

Then, more than a year later, in January 2017, the heavily distorted single — a far cry from the polished production of most mainstream hits — exploded onto the charts, attracting an endorsement from rapper A$AP Rocky and prompting Adam Grandmaison, a tattooed former BMX biker and hip-hop tastemaker, to sign on as Onfroy’s manager. There was so much hype that when Drake previewed a similar-sounding song January 28, fans accused him of plagiarism, which compounded Onfroy’s fame.

Throughout all of this, the rapper maintained his innocence to the domestic abuse charges. His attorney David Bogenschutz declined New Times’ request for comment on the defense, and his management has made no official public statement rebutting the allegations. But in a recorded call from jail that was widely shared on social media, Onfroy claimed Ayala had cheated on him and then blackmailed him. She had been hit by someone else, he said. “Geneva fucked my homeboy… She tried to bribe me and my mother and my people for $3,000,” he says, laughing. “Stop believing the motherfucking rumors. I did not beat that bitch; she got jumped. Bye.”

“Stop believing the rumors. I did not beat that bitch; she got jumped.”

tweet this

In another call that also was passed around social media, he claimed Ayala had never been pregnant: “For all you dumb fuck ass niggas that thought this stupid bitch was pregnant, I’ve got the paperwork signifying that she wasn’t pregnant. So when I get out, I’ll fuck all your little sisters in the fucking throat hole.”

As Onfroy sat behind bars, media began to question whether the controversy had fueled his fame. In February 2017, Pitchfork published the 2,200-word piece “XXXTentacion Is Blowing Up Behind Bars, but Should He Be?” and a March Washington Post article about “Look at Me!” wondered whether Onfroy’s rise had “more to do with the public’s ghoulish interest in the repugnant crimes he may have committed.”

Nearly six months after his arrest, Onfroy left Broward County Jail after pleading no contest to his 2015 charges of armed home invasion, robbery, and aggravated battery with a firearm. He got out March 26 and, just days later, announced a surprise show in downtown Miami. The rapper barely promoted the event, but by 9:30 p.m. April 7, a massive line had formed outside the venue.

One attendee, Sebastian Alsina, estimated in a blog post that more than 350 people crowded into the small warehouse. But before Onfroy could perform, a squadron of cops in full tactical gear crashed the party and pushed their way to the front. They called for the venue’s managers and insisted everyone leave. Instead, the crowd rioted. “The streets were flooded,” Alsina wrote. “Cars were being jumped on, people were being trampled, bottles being shattered just to get a sight of X.”

The surprise show foreshadowed the next year of extreme commercial success and sinister developments in the rapper’s criminal case. Onfroy would soon drop two mixtapes and embark upon a nearly sold-out tour. He joined the ranks of hip-hop magazine XXL’s 2017 “Freshman Class,” a major list of up-and-coming artists. (“He really won by a landslide as far as the #1 pick,” XXL editor in chief Vanessa Satten told the morning talk show The Breakfast Club.) In August, “Look at Me!” went certified platinum, and Onfroy released his first album, 17, which debuted at number two on the Billboard albums chart. Weeks later, Onfroy signed a reported $6 million record deal with Caroline, a subsidiary of Capitol Records.

Though his fame grew, Onfroy’s reputation soured. After he appeared in the XXL list, many publications criticized the magazine. “XXXTentacion should not be on this cover,” Tom Breihan wrote in a June article on Stereogum, a music website. “We should not continue to make him famous.” The same month, the Outline, another website, published the article “Do Not Co-Sign XXXTentacion.” In September 2017, Pitchfork published new details of Ayala’s alleged abuse, prompting more publications to pull back from covering him.

The rapper tried to repair the damage. In October, he announced plans to donate more than $100,000 to a domestic abuse charity. Then, in December, he planned an “anti-rape” event during Art Basel Miami Beach. But neither effort bore fruit: The anti-rape event was canceled after one of his fans vandalized the venue, and Onfroy says he never donated to any abuse charities, electing instead to contribute to several children’s causes.

On November 27, 2017, Onfroy’s attorneys submitted a document signed by Ayala, stating she would not testify against him in court. Ayala now says she signed it at the rapper’s request, knowing that prosecutors, not victims, decide whether to pursue domestic abuse charges. “And I was scared,” she says. “He always invited all his fans to go to every court appearance… When I walk out of the courtroom and onto the street, what are people going to do?”

Suspecting coercion, prosecutors over the next few weeks charged Onfroy with 15 counts of witness tampering and harassment relating to both the domestic abuse charges and earlier alleged crimes. As evidence, they submitted recordings of 213 phone calls the singer made from jail to friends and witnesses including Ayala. When New Times requested to hear the calls under Florida’s Sunshine Law, Onfroy’s lawyers objected, claiming among other things that the audio was exempt because it amounted to a “confession.” A judge granted an emergency hearing in private and then sealed the records until this September.

XXXTentacion crowd-surfing at Rolling Loud 2017 in Bayfront Park in downtown Miami

Photo by Alex Markow

The new charges affirmed the media’s distaste for Onfroy but didn’t deter fans. When his second album, ?, dropped in March 2018, it quickly garnered enough sales and streams to hit the top of the Billboard charts. Its success placed Onfroy in the league of top chart staples such as Drake, J. Cole, and Kendrick Lamar.

The 18-track, 37-minute album is an exercise in breaking down genre barriers, jumping between trap, alt-rock, metal, and reggaeton — an explicit effort to please everyone. “I was trying to appeal to every market,” Onfroy said in an April interview. “Even if there’s someone who doesn’t like the entire album, you have to like at least one song.”

The question of how to treat Onfroy’s music remains tricky. Just last month, the streaming platform Spotify announced a new “hateful conduct” policy that prohibited the music of Onfroy and accused sexual predator R. Kelly on its playlists. Many applauded the gesture. But, as a spokesperson for Onfroy pointed out on Twitter, the new policy excluded many other alleged — largely white — abusers, including David Bowie and Gene Simmons of Kiss. Just two weeks later, Spotify reversed its policy, reportedly because several artists, including Kendrick Lamar, threatened to pull their music from the platform. (For more on the Spotify banning and reinstatement, click here.) The question of ethical listening will likely come up again soon, however, because Onfroy has intimated a new album might drop in June.

Five: Violence, Power, and Harassment

Back in Parkland, in the dim recording studio of his $1.4 million home, Onfroy explains why he’s not a feminist. Feminists aren’t looking for equality, he says. They want empowerment. “Women may see or feel that they’re belittled,” he says, “but you’re only belittled if you want to be belittled.” Take, for instance, Hillary Clinton, he says. “She ran [for president] and she wasn’t killed for it. That says everything.”

In this post-#MeToo moment, when abuse allegations “can go off hearsay,” Onfroy argues, “women are almost more powerful than men.”

After coming forward with her allegations, Ayala was abandoned by many of her friends. Only Talyssa Lee, the stranger she’d met in Orlando, stood by her story publicly. Ayala received phone calls from Onfroy’s family and friends telling her to drop the charges.

Much of the harassment often came online. Ayala’s Twitter account was hacked and taken over by an impersonator, who tweets often about Onfroy. Her Instagram account was deleted after too many fans “reported” her posts.

But people tracked her in real life too. She took a job at a Dunkin’ Donuts but had been working there only a week before Onfroy’s fans found her. They began showing up every day, harassing her, taking photos of her, and trying to follow her home. Ayala quit after three weeks. “I can’t even go to the mall or Walmart without being noticed and eyed down,” she says.

Perhaps most disturbing, after he allegedly beat her in the apartment near FIU, Ayala found herself in need of surgery to repair nerve damage and a fracture near her eye. The procedure would cost around $20,000, so Ayala, who has no health insurance, set up a GoFundMe campaign to crowdsource the money. The page quickly raised several thousand dollars, including $5,000 from Onfroy himself.

But within a week, GoFundMe received reports from Onfroy’s fans claiming Ayala had misrepresented the cause of her injuries. So the website deleted her page, freezing the funds that had been raised. When New Times reached out to GoFundMe for comment, the company investigated the suspension. A spokesperson wrote back the following:

If a campaign is reported, our team looks into it to request sufficient information regarding the use of funds. In this case, the campaign was reported to us, and we reached out to the campaign organizer to collect additional information. Sufficient information was provided, and the campaign has been reactivated.Nearly two years after they first met, Ayala now rents a room in a house 20 minutes south of Onfroy’s place. It’s the first room she’s had to herself. “I’m saving up to move somewhere else,” she says, “somewhere in the country, where there aren’t any people.”

Click this link to read “XXXTentacion: An Annotated Timeline of New Times Coverage”

Thank you for reading this post The Real Story of South Florida Rapper XXXTentacion at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: