You are viewing the article The Final Years of Vincent van Gogh at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

On July 27, 1890, Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh shot himself with a 7mm revolver in Auvers-sur-Oise, a village less than an hour north of Paris. He died two days later, at age 37. Van Gogh had come to Auvers some 10 weeks earlier after two years in the South of France, where a mental breakdown resulted in a lengthy stint in an asylum. Van Gogh hoped his new surroundings would restore his frail psyche, to no avail. But his painful last years and final days would also see him create much of the art that made him a legend.

Van Gogh and his brother were devoted to each other

Born in March 1853, van Gogh was the eldest of five surviving children born to Anna and Theodorus, a Protestant minister. He had a peripatetic early career, working for an art dealer in the Netherlands and London, as a missionary to a poor community in Belgium and briefly (but seriously) considering becoming a minister himself.

Throughout his life, van Gogh experienced periods of psychological and physical isolation, instability and depression. He was often malnourished and in ill health, and he suffered a series of thwarted romantic relationships with women. It was only in his late 20s that he fully turned to art, encouraged in part by his younger brother Theo, a Paris-based art dealer. The two were devoted to each other. Theo provided emotional and financial support for Vincent, and the brothers exchanged hundreds of letters.

Van Gogh moved to Paris in 1886. Theo had little success in marketing his brother’s work (van Gogh sold just one painting during his lifetime), but he did introduce Vincent to the flourishing avant-garde French art scene, including painters Georges Seurat, Camille Pissarro and Paul Gaugin. Van Gogh and Gaugin became close friends. When van Gogh decided to move to Arles in February 1888, he hoped to entice Gaugin and others to join him in establishing an artist’s colony there.

He cut off his left earlobe after a fight with another artist

The landscape and unique light of southern France unleashed van Gogh’s creativity, and his paintings and palette took on new depths of color and emotion. He worked quickly and constantly, churning out 300 oil paintings, drawings and watercolors. He rented rooms in a local building, the Yellow House, using it as a studio for several months while he lived in a series of inns nearby. He painted portraits of his landlords, acquaintances and the town’s residents, who looked upon him as talented, but volatile, high-strung and unusual.

In October 1888, Gaugin finally arrived in Arles. The two artists lived and worked together at the Yellow House, but their differing temperaments clashed, and the friendship soon soured. Gaugin’s arrogance and domineering personality unsettled van Gogh, fostering a deep sense of inadequacy and a fear of abandonment.

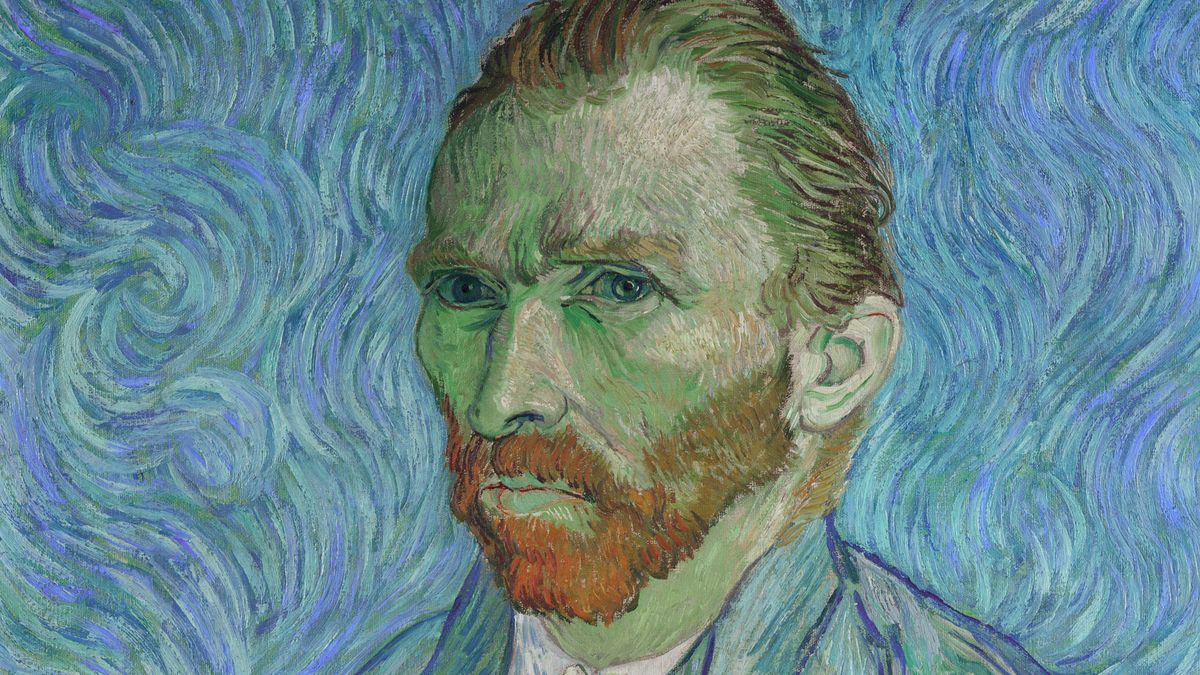

Things came to a head on December 23. Gaugin would later claim that van Gogh attacked him with a knife. But what is certain is that van Gogh violently turned the knife on himself, cutting off his left earlobe. He wrapped the bloody ear in paper and delivered it to a woman at a local brothel, before passing out in his room. When he was discovered the next day, he had no memory of his self-mutilation, likely a sign of a complete psychotic breakdown. Gaugin quickly fled Arles, and the two men never saw each other again. Van Gogh later captured the aftermath of the event in a series of self-portraits with his bandaged ear.

Van Gogh spent the next several months in and out of hospitals, as his condition worsened. Many of the residents of Arles turned on him. Some referred to him as “le fou roux” (the redheaded madman), and dozens signed a petition demanding he be forced to leave the town.

READ MORE: How Vincent van Gogh’s Tumultuous Friendship with Paul Gauguin Drove Him to Cut Off His Ear

Van Gogh checked himself into an asylum

In May 1889, van Gogh voluntarily entered the Saint-Paul asylum in nearby Saint-Rémy. More than a century after his death, scientists and historians continue to debate the cause of his mental instability. The most widely-accepted diagnosis is bipolar disorder, given his “manic” outbursts of energy and creativity followed by long, debilitating depressions. Félix Ray, van Gogh’s doctor in Arles, diagnosed him with epilepsy, though that has been dismissed by many modern scholars, as has an alternate theory that he suffered from advanced porphyria.

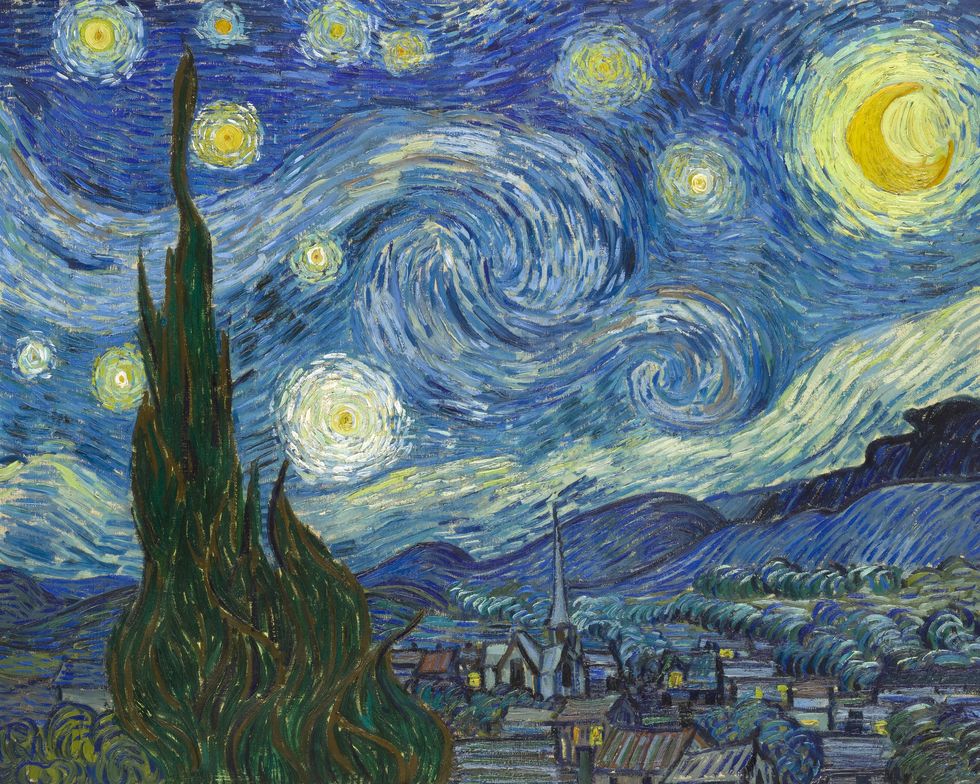

Van Gogh was initially allowed to work outside the asylum under supervision, and his condition briefly improved, before worsening. Unable to visit his beloved landscapes, he was reduced to painting from memory or depicting his immediate surroundings. Despite these limitations, he produced notable works during this period, including the legendary “The Starry Night,” which shows the view from his asylum window.

Feeling lonely and isolated, van Gogh committed suicide

Increasingly discouraged and fatalistic about his chances of recovery while in Saint-Rémy, van Gogh discharged himself in May 1890. Eager to be closer to Theo, and desperate for a new beginning, he moved north. He settled in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, taking a room at the Auberge Ravoux. He also began seeing Dr. Paul Gachet, who had previously treated Camille Pisarro, Auguste Renoir and others. Gachet, who specialized in nervous disorders and natural medicine, was an amateur artist himself, and Theo hoped that his sensitive nature would be beneficial to Vincent. In the century since, many have criticized Gachet’s unconventional treatment of van Gogh, but the two men quickly developed a close bond.

Van Gogh’s output during his 10 weeks in Auvers was astounding. He may have completed 70 works in as many days, as he was once again inspired by his new environment. But much of his work from this final period is also wild and dramatic, as the brilliant intensity — and instability — within poured out on his canvases. One of his final paintings, “Wheatfield With Crows,” depicts an isolated, windswept field and a flock of crows — birds are often used to depict death and rebirth.

Van Gogh wrote openly to Theo and others of his loneliness and isolation, although he also expressed hope for both a mental recovery and artistic and financial success. His work was increasingly being shown in Paris and elsewhere around Europe, as his reputation slowly grew. But he also ignored much of Dr. Gachet’s advice, continuing to incessantly smoke and drink. His mood worsened when he learned that Theo, already under duress due to his financial support of his brother, had suffered a setback at his job.

Historians do not know if there was a final impetus for van Gogh’s suicide, but on July 27, he likely walked to a nearby field or barn and shot himself. The bullet missed his vital organs but lodged so deeply in his body doctors were unable to remove it. Van Gogh was able to walk to the Auberge Ravoux, where an innkeeper found him. Dr. Gachet and others were summoned. Theo soon arrived and was with van Gogh when he died from an infection on July 29.

Theo never recovered his brother’s death and died just months later. His body was later reinterred beside his beloved brother in the municipal cemetery at Auvers. In the decades after the brothers’ deaths, it was Theo’s widow, Johanna, who worked tirelessly to posthumously promote van Gogh’s work, eventually helping to make him one of the most famous and well-respected painters in history.

Thank you for reading this post The Final Years of Vincent van Gogh at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: