You are viewing the article Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” Speech May Not Have Contained That Famous Phrase at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

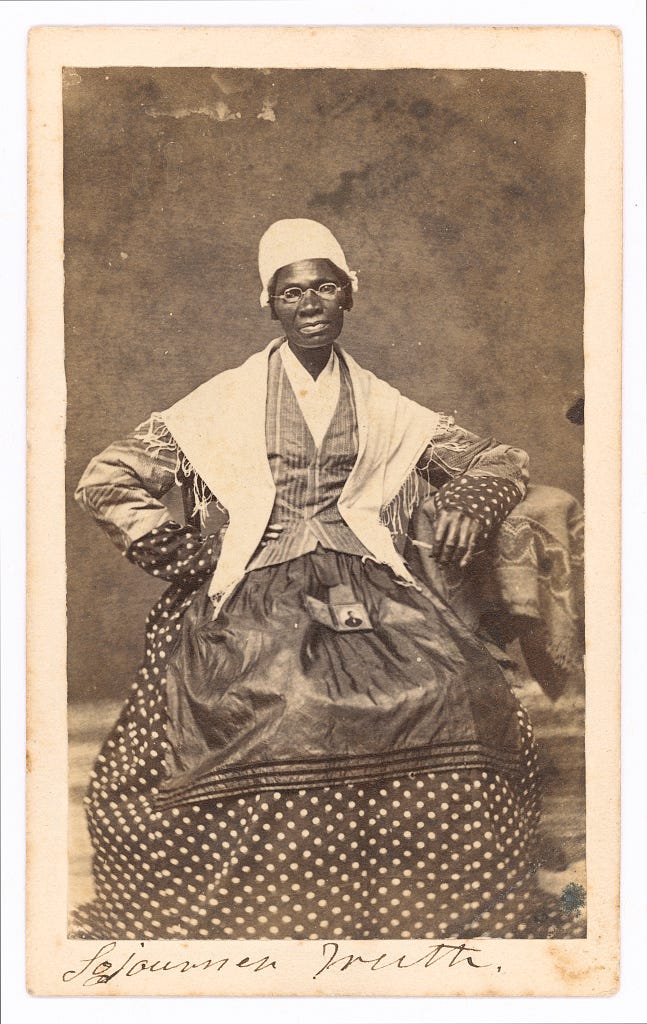

During Sojourner Truth’s famous 1851 speech at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, she used the phrase “Ain’t I a Woman?” four times to emphasize the need to fight for equal rights for African American women.

Or says a transcript of the speech that was published 12 years later.

Fellow abolitionist Frances Gage published Truth’s speech in the New York Independentin 1863, but little of it lines up with the transcript published a month after the convention by Reverend Marius Robinson in Anti-Slavery Bugle in 1851.

To this day, the accuracy of both transcripts is constantly being debated, with the two versions being pitted against each other side by side by experts, including the Sojourner Truth Project.

But one thing’s for certain: Whatever her syntax that day, the words Truth spoke were powerful and will forever be remembered as one of the greatest speeches of the women’s abolitionist movement.

Born into slavery, Truth was sold a few times as a child

Truth was born Isabella Baumfree around 1797 (records of the enslaved children’s births weren’t kept), in Swartekill, New York, to an enslaved father, James, who was captured in Ghana and a mother, Elizabeth, who was the daughter of enslaved people from Guinea.

Owned by Colonel Hardenbergh in Esopus, New York, which was under Dutch control, Truth grew up speaking Dutch. After both the colonel and his son died, Truth was sold off along with a flock of sheep for $100. Also known as Belle, the nine-year-old was eventually sold a couple more times and came to learn English under her owner John Dumont who lived in West Park, New York.

Reportedly “inspired by her conversations with God, which she held alone in the woods,” Truth escaped to freedom in 1826 with her young daughter, Sophia. While Dumont accused her of running away, she stated boldly, “I did not run away, I walked away by daylight.”

She changed her name to Sojourner Truth after a ‘religious conversation’

By 1828, Truth had settled in New York City and became a preacher. She started speaking out about her experience as an enslaved person and advocating for abolitionism and feminism, while quickly gaining a reputation as a powerful speaker.

But it wasn’t until 1843 when she had a “religious conversion” and was “called in spirit” to “travel up and down the land” as a lecturer that she adopted the name Sojourner Truth. In 1844, she joined Northampton Association of Education and Industry, which also included William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass. Truth continued speaking wherever she went — and also selling her book The Narrative of Sojourner Truth — winning over audiences with her artful persuasion.

In 1850, by the time she stepped up to the podium at the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts she was already one of the most influential voices of the movement.

There are several accounts of what Truth said in her speech

The following year, the Women’s Rights Convention moved to Akron on May 29, 1851. “Everything seemed to go wrong with the meeting,” according to the New Republic. “A number of ministers had invaded the hall uninvited and monopolized the discussion, quoting biblical texts to the effect that women should eschew all activities except those of child-bearing, homemaking and subservience to their husbands.”

Taking place at High Street’s Old Stone Church, the gifted speaker didn’t outrightly prepare anything. But when she heard these comments, she couldn’t sit still. Truth stepped up and spoke out extemporaneously, or as the New Republic says, “Suddenly she boomed out of the hushed audience.”

And the words she said are now what’s so hotly debated by historians, even today.

The version that was printed by Robinson a month later, starts out, “May I say a few words? I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights.”

That final sentence is as close as it gets to the phrasing “Ain’t I a Woman,” which we know the speech as today.

In the second version — printed a dozen years later — “Ain’t I a Woman” is used four times, and even detailed by some historians as “Ar’n’t I a woman?”

The newer version weaves the phrase throughout poetically, showing the hardships women face.

The iconic section reads: “That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man — when I could get it — and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?”

While there are similarities in essence, the disputed transcripts hardly line up, making the debate over accuracy still rage today.

Some researchers point to the fact that some of the statements in Gage’s version simply aren’t true. For instance, Truth only had five children — not 13 — an inaccuracy that immediately pokes holes in the later version.

That said, Gage herself was a poet and may have taken artistic license to embellish and emphasize the statements — or perhaps she simply meant them to be a fictionalized representation the plight of all women.

The dialect differences between the two versions also raise potential issues, with some saying the latter captures Truth’s Afro-Dutch dialect more accurately.

Modern interpretations favor Gage’s version

Many readings of Truth’s famous speech have been recorded, including some by notable actresses like Kerry Washington and Alfre Woodward, as well The Color Purple author Alice Walker. All three readings follow the latter transcript containing the “Ain’t I a Woman” phrasing — with audiences laughing knowingly throughout the speech.

Whether or not those words were used, Truth’s sentiment was considered extreme at the time as she advocated for political equality for all women. And more than a century since her speech, Truth’s words continue to resonate with generations, being taught in schools and “Ain’t I a Woman” emblazoned on t-shirts, posters, pins and more.

Truth continued speaking throughout the rest of her life, advocating for women’s rights, equality and suffrage — until her death in Battle Creek, Michigan in 1883.

Thank you for reading this post Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” Speech May Not Have Contained That Famous Phrase at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: