You are viewing the article Ruby Bridges at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

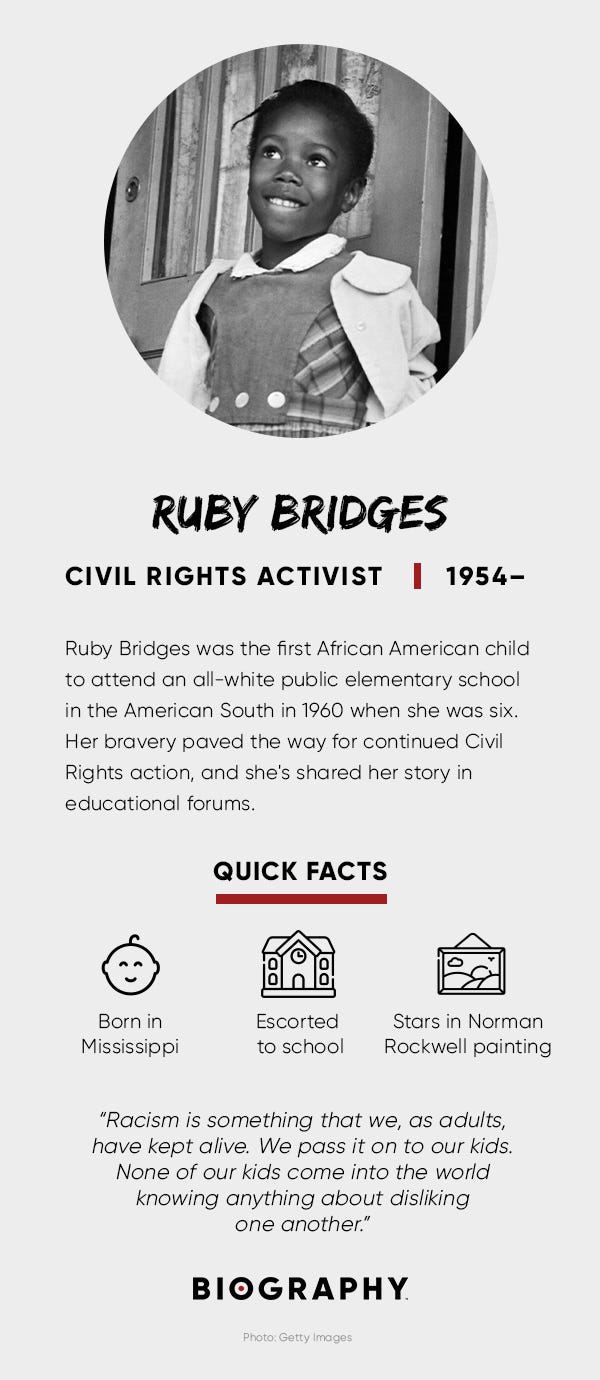

Ruby Bridges is an iconic figure in American civil rights history, renowned for her bravery and determination as she became the first African American child to attend a white elementary school in the segregated South. Born in 1954, Bridges was just six years old when she entered the William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1960. Her unwavering commitment to education and her indomitable spirit in the face of adversity not only transformed her own life, but also served as a catalyst for the desegregation of public schools across the United States. This introduction will explore the remarkable journey of Ruby Bridges and shed light on the lasting impact she has had on the civil rights movement.

(1954-)

Who Is Ruby Bridges?

Ruby Bridges was six when she became the first African American child to integrate a white Southern elementary school. On November 14, 1960, she was escorted to class by her mother and U.S. marshals due to violent mobs. Bridges’ brave act was a milestone in the civil rights movement, and she’s shared her story with future generations in educational forums.

Early Life

Ruby Nell Bridges was born on September 8, 1954, in Tylertown, Mississippi. She grew up on the farm her parents and grandparents sharecropped in Mississippi.

When she was four years old, her parents, Abon and Lucille Bridges, moved to New Orleans, hoping for a better life in a bigger city.

Her father got a job as a gas station attendant and her mother took night jobs to help support their growing family. Soon, young Bridges had two younger brothers and a younger sister.

Education and Facts

The fact that Bridges was born the same year that the Supreme Court handed down its Brown v. Board of Education decision desegregating schools is a notable coincidence in her early journey into civil rights activism.

When Bridges was in kindergarten, she was one of many African American students in New Orleans who were chosen to take a test determining whether or not she could attend a white school. It is said the test was written to be especially difficult so that students would have a hard time passing. The idea was that if all the African American children failed the test, New Orleans schools might be able to stay segregated for a while longer.

Bridges lived a mere five blocks from an all-white school, but she attended kindergarten several miles away, at an all-Black segregated school. Bridges’ father was averse to his daughter taking the test, believing that if she passed and was allowed to go to the white school, there would be trouble. However, her mother, Lucille, pressed the issue, believing that Bridges would get a better education at a white school. She was eventually able to convince Bridges’ father to let her take the test

In 1960, Bridges’ parents were informed by officials from the NAACP that she was one of only six African American students to pass the test. Bridges would be the only African American student to attend the William Frantz School, near her home, and the first Black child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South.

School Desegregation

When the first day of school rolled around in September, Bridges was still at her old school. All through the summer and early fall, the Louisiana State Legislature had found ways to fight the federal court order and slow the integration process. After exhausting all stalling tactics, the Legislature had to relent, and the designated schools were to be integrated that November.

Fearing there might be some civil disturbances, the federal district court judge requested the U.S. government send federal marshals to New Orleans to protect the children. On the morning of November 14, 1960, federal marshals drove Bridges and her mother five blocks to her new school. While in the car, one of the men explained that when they arrived at the school, two marshals would walk in front of Bridges and two would be behind her.

When Bridges and the federal marshals arrived at the school, large crowds of people were gathered in front yelling and throwing objects. There were barricades set up, and policemen were everywhere.

Bridges, in her innocence, first believed it was like a Mardi Gras celebration. When she entered the school under the protection of the federal marshals, she was immediately escorted to the principal’s office and spent the entire day there. The chaos outside, and the fact that nearly all the white parents at the school had kept their children home, meant classes weren’t going to be held at all that day.

Ostracized at Elementary School

On her second day, the circumstances were much the same as the first, and for a while, it looked like Bridges wouldn’t be able to attend class. Only one teacher, Barbara Henry, agreed to teach Bridges. She was from Boston and a new teacher to the school. “Mrs. Henry,” as Bridges would call her even as an adult, greeted her with open arms.

Bridges was the only student in Henry’s class because parents pulled or threatened to pull their children from Bridges’ class and send them to other schools. For a full year, Henry and Bridges sat side by side at two desks, working on Bridges’ lessons. Henry was loving and supportive of Bridges, helping her not only with her studies but also with the difficult experience of being ostracized.

Bridges’ first few weeks at Frantz School were not easy ones. Several times she was confronted with blatant racism in full view of her federal escorts. On her second day of school, a woman threatened to poison her. After this, the federal marshals allowed her to only eat food from home. On another day, she was “greeted” by a woman displaying a Black doll in a wooden coffin.

Bridges’ mother kept encouraging her to be strong and pray while entering the school, which Bridges discovered reduced the vehemence of the insults yelled at her and gave her courage. She spent her entire day, every day, in Mrs. Henry’s classroom, not allowed to go to the cafeteria or out to recess to be with other students in the school. When she had to go to the restroom, the federal marshals walked her down the hall.

Several years later, federal marshal Charles Burks, one of her escorts, commented with some pride that Bridges showed a lot of courage. She never cried or whimpered, Burks said, “She just marched along like a little soldier.”

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY’S RUBY BRIDGES’ FACT CARD

Effect on the Bridges Family

The abuse wasn’t limited to only Bridges; her family suffered as well. Her father lost his job at the filling station, and her grandparents were sent off the land they had sharecropped for over 25 years. The grocery store where the family shopped banned them from entering. However, many others in the community, both Black and white, began to show support in a variety of ways. Gradually, many families began to send their children back to the school and the protests and civil disturbances seemed to subside as the year went on.

A neighbor provided Bridges’ father with a job, while others volunteered to babysit the four children, watch the house as protectors, and walk behind the federal marshals on the trips to school.

Signs of Stress

After winter break, Bridges began to show signs of stress. She experienced nightmares and would wake her mother in the middle of the night seeking comfort.For a time, she stopped eating lunch in her classroom, which she usually ate alone. Wanting to be with the other students, she would not eat the sandwiches her mother packed for her, but instead hid them in a storage cabinet in the classroom.

Soon, a janitor discovered the mice and cockroaches who had found the sandwiches. The incident led Mrs. Henry to lunch with Bridges in the classroom.Bridges started seeing child psychologist Dr. Robert Coles, who volunteered to provide counseling during her first year at Frantz School. He was very concerned about how such a young girl would handle the pressure. He saw Bridges once a week either at school or at her home.

During these sessions, he would just let her talk about what she was experiencing. Sometimes his wife came too and, like Dr. Coles, she was very caring toward Bridges. Coles later wrote a series of articles for Atlantic Monthly and eventually a series of books on how children handle change, including a children’s book on Bridges’ experience.

Overcoming Obstacles

Near the end of the first year, things began to settle down. A few white children in Bridges’ grade returned to the school. Occasionally, Bridges got a chance to visit with them. By her own recollection many years later, Bridges was not that aware of the extent of the racism that erupted over her attending the school. But when another child rejected Bridges’ friendship because of her race, she began to slowly understand.

By Bridges’ second year at Frantz School, it seemed everything had changed. Mrs. Henry’s contract wasn’t renewed, and so she and her husband returned to Boston. There were also no more federal marshals; Bridges walked to school every day by herself. There were other students in her second-grade class, and the school began to see full enrollment again. No one talked about the past year. It seemed everyone wanted to put the experience behind them.

Bridges finished grade school and graduated from the integrated Francis T. Nicholls High School in New Orleans. She then studied travel and tourism at the Kansas City business school and worked for American Express as a world travel agent.

Husband and Children

In 1984, Bridges married Malcolm Hall in New Orleans. She later became a full-time parent to their four sons.

Norman Rockwell Painting

In 1963, painter Norman Rockwell recreated Bridges’ monumental first day at school in the painting, “The Problem We All Live With.” The image of this small Black girl being escorted to school by four large white men graced the cover of Look magazine on January 14, 1964.

The Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, now owns the painting as part of its permanent collection. In 2011, the museum loaned the work to be displayed in the West Wing of the White House for four months upon the request of President Barack Obama.

Book and Movie

‘The Story of Ruby Bridges’

In 1995, Robert Coles, Bridges’ child psychologist and a Pulitzer-Prize winning author, published The Story of Ruby Bridges, a children’s picture book depicting her courageous story.

Soon after, Barbara Henry, her teacher that first year at Frantz School, contacted Bridges and they were reunited on TheOprah WinfreyShow.

‘Ruby Bridges’

“Ruby Bridges” is a Disney TV movie, written by Toni Ann Johnson, about Bridges’ experience as the first Black child to integrate an all-white Southern elementary school.

The two-hour film, shot entirely in Wilmington, North Carolina, first aired on January 18, 1998, and was introduced by President Bill Clinton and Disney CEO Michael Eisner in the Cabinet Room of the White House.

Ruby Bridges Foundation

In 1999, Bridges formed the Ruby Bridges Foundation, headquartered in New Orleans. Bridges was inspired following the murder of her youngest brother, Malcolm Bridges, in a drug-related killing in 1993 — which brought her back to her former elementary school.

For a time, Bridges looked after Malcolm’s four children, who attended William Frantz School. She soon began to volunteer there three days a week and soon became a parent-community liaison.

With Bridges’ experience as a liaison at the school and her reconnection with influential people in her past, she began to see a need for bringing parents back into the schools to take a more active role in their children’s education.

Bridges launched her foundation to promote the values of tolerance, respect and appreciation of differences. Through education and inspiration, the foundation seeks to end racism and prejudice. As its motto goes, “Racism is a grown-up disease, and we must stop using our children to spread it.”

In 2007, the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis unveiled a new exhibition documenting Bridges’ life, along with the lives of Anne Frank and Ryan White.

QUICK FACTS

- Birth Year: 1954

- Birth date: September 8, 1954

- Birth State: Mississippi

- Birth City: Tylertown

- Birth Country: United States

- Best Known For: Ruby Bridges was the first African American child to integrate an all-white public elementary school in the South. She later became a civil rights activist.

- Industries

- Civil Rights

- Education and Academia

- Astrological Sign: Virgo

- Schools

- William Frantz Elementary School

- Interesting Facts

- In 1960, Ruby Bridges became the first African American child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South.

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn’t look right,contact us!

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Ruby Bridges Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/activists/ruby-bridges

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: February 23, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

QUOTES

- My message is really that racism has no place in the hearts and minds of our children.

- I’ve been told that my ideas are grandiose. Yes, they are. However, so were the ideas that marched me through screaming crowds and up the stairs of William Frantz Elementary more than 50 years ago.

- In order to truly make lasting positive change—to keep Dr. King’s dream moving forward—we need to think big and act big.

- That first morning I remember mom saying as I got dressed in my new outfit, ‘Now, I want you to behave yourself today, Ruby, and don’t be afraid. There might be a lot of people outside this new school, but I’ll be with you.’

- I wish there were enough marshals to walk with every child as they faced the hatred and racism today, and to support, encourage them the way these federal marshals did for me.

- My mother said to me, ‘Ruby, if I’m not with you and you’re afraid, then always say your prayers.’

- There were lots of people outside, and they were screaming and shouting and the police officers. But I thought it was Mardi Gras, you know, I didn’t know that all of that was because of me.

- Racism is something that we, as adults, have kept alive. We pass it on to our kids. None of our kids come into the world knowing anything about disliking one another.

- I believe that history should be taught in a different way. History definitely should be taught the way it happened—good, bad or ugly. History is sacred. For me history is a foundation and the truth.

- [My teacher Mrs. Henry] taught me what Dr. King tried to teach all of us. We should never judge a person by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. That was the lesson I learned at 6 years old.

In conclusion, Ruby Bridges is a powerful symbol of bravery, resilience, and the fight for equality. Through her own determination and the support of her family and community, she became a trailblazer in the civil rights movement. Despite facing immense opposition and hatred, Ruby remained strong, setting an example for future generations that change is possible even in the face of adversity. Her legacy extends far beyond her own personal story, inspiring countless others to stand up against injustice and pursue equal opportunities for all. Ruby Bridges serves as a reminder that each individual has the power to make a difference and change the world for the better.

Thank you for reading this post Ruby Bridges at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. Ruby Bridges – Who is she and what is her story?

2. Ruby Bridges – How did she become the first African American child to attend an all-white school?

3. Ruby Bridges – What challenges did she face during her integration of William Frantz Elementary School?

4. Ruby Bridges – What impact did her bravery have on the Civil Rights Movement?

5. Ruby Bridges – Are there any books or documentaries about her life?

6. Ruby Bridges – Where is she today and what is she doing?

7. Ruby Bridges – Did she receive any recognition or awards for her efforts?

8. Ruby Bridges – How did her experience as a child activist shape her advocacy work later in life?

9. Ruby Bridges – Did she face any backlash or threats during her time at the all-white school?

10. Ruby Bridges – What lessons can we learn from her story and apply to modern-day racial equality issues?