You are viewing the article Roald Dahl Wrote ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ During the ‘Most Difficult Years of His Life’ at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

The thrill of the Golden Ticket, the wonderment of a chocolate factory and the whimsy of the Oompa-Loompas: The sugary sweet world imagined in Roald Dahl’s book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has made it one of the most beloved tales in children’s literature.

With at least 20 million copies sold globally in 55 different languages, the 1964 book continues to lure readers of all ages in with its rags-to-riches tale of a young boy Charlie Bucket whose life changes when he finds that coveted shiny ticket in his chocolate bar wrapper.

But for Dahl, the story was the result of decades of an idea marinating in his head mixed with a period of family tragedy. “It starts always with a tiny little seed of an idea, a little germ, and that even doesn’t come very easily,” the British author told Scholastic of his story ideas. But ultimately it was his love for childlike fun that helped create a universal story with such iconic characters. “My lucky thing is I laugh at exactly the same jokes that children laugh at.”

As a child, Dahl imagined working at a Cadbury chocolate factory

At the age of 13, Dahl left his first British boarding school of St. Peter’s in Weston-super-Mare in 1929 and moved to Repton School in South Derbyshire. And his new school came with an unexpected perk: free chocolate!

The Cadbury chocolate company would send samples to the students in nondescript packaging to get their thoughts as a test audience. Dahl’s experience as a teenage chocolate taster got his wheels spinning about what the candy-making process must be like.

“It was then I realized that inside this great Cadbury’s chocolate factory there must be an inventing room, a secret place where fully-grown men and women in white overalls spent all their time playing around with sticky boiling messes, sugar and chocs, and mixing them up and trying to invent something new and fantastic,” he wrote in a speech.

And soon he imagined himself in that scenario, coming up with the perfect chocolate treat. “I would rush out into the corridor, clutching my new invention and go bursting straight into the office of the great Mr. Cadbury himself,” he continued, adding that the candy man’s face would “light up,” and he’d make him a director and give him two Rolls-Royces. “I used to lie in bed at night at that boarding school, dreaming up more and more fantastic successes that I had with Mr. Cadbury in his factory.”

C.S. Forester motivated Dahl to start writing

Those teenage dreams were set aside as he sought his own real-life adventures. After an expedition to Newfoundland, he started working for Shell Oil in 1934 in London before transferring to the office in Dar-es-Salaam, in what is now Tanzania. World War II cut short his time there, so he joined the Royal Air Force in 1939 in Nairobi. After stints in Libya and Greece, he ended up in Washington, D.C., as an assistant air attaché for the British Embassy in 1942. It was in the U.S. capital that he met British novelist C.S Forester, who encouraged him to start writing.

Dahl quickly found success and had a variety of genres of published work under his belt: a Walt Disney/Random House book The Gremlins in 1943, a short story collection in 1946, a dystopian adult novel Some Time Never in 1948 and a stage play The Honeys in 1955 — plus his stories started appearing on Alfred Hitchcock Presents in 1957.

READ MORE: Roald Dahl Was a WW II Spy and Fighter Pilot Before Becoming a Beloved Children’s Book Author

Dahl put his writing on hold after his baby son’s tragic accident

As he was honing his writing skills, Dahl never forgot about his chocolate factory fantasy. And it was after the joy he felt from writing James and the Giant Peach, which was published in 1961, that he resurrected the idea and started writing what was called at the time Charlie’s Chocolate Boy in 1960.

Along with the professional fulfillment came a personal one too: the birth of his first and only son Theo — with American actress Patricia Neal — in 1960. But what should have been a joyous time for the family turned tragic when the family’s nanny Susan Denson was pushing the 4-month-old in a stroller in New York City and it was hit by a cab.

The child suffered unimaginable injuries: his skull “shattered” and he was diagnosed with “neurological deficit.” Dahl had been in his apartment writing — likely working on Charlie — when the accident occurred.

His priorities shifted immediately as he became fully focused on this infant son’s care. Even after nine surgeries to treat the baby’s head trauma, excess fluid kept filling his brain and threatening his eyesight. But the author stopped at nothing. He eventually asked a toymaker acquaintance Stanley Wade to help build a device.

“Dahl gave up writing for 18 months or more, and devoted himself to inventing a shunt which would help save his son’s life,” Dahl official biographer Donald Sturrock, who he met in 1985, told Vanity Fair. Eventually, he helped come up with the Dahl-Wade-Till (DWT) valve. While Theo was already on his way to recovery by the time it was complete, the device did end up helping 3,000 other children.

He paused writing ‘Charlie’ after his daughter contracted measles and passed away

For a fresh start, the family returned to England in 1961 — and settled into a nice routine. His wife was away filming Hud with Paul Newman in 1962 and he started working on Charlie again — until one day his oldest daughter, 7-year-old Olivia, came home from school with measles.

“As the illness took its usual course, I can remember reading to her often in bed and not feeling particularly alarmed about it,” Dahl wrote in 1986. “Then one morning, when she was well on the road to recovery, I was sitting on her bed, showing her how to fashion little animals out of colored pipe cleaners, and when it came to her turns to make one herself, I noticed that her fingers and her mind were not working together.”

The young girl told her father she just felt sleepy. “In an hour, she was unconscious. In 12 hours, she was dead,” he wrote.

Needless to say, her death stunned him completely. “Dahl went into the greatest depression of his life after his daughter’s death,” Sturrock told Vanity Fair.

READ MORE: Roald Dahl’s Daughter Tragically Died From Measles at Seven Years Old

Dahl poured his emotions into his writing and finished ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’

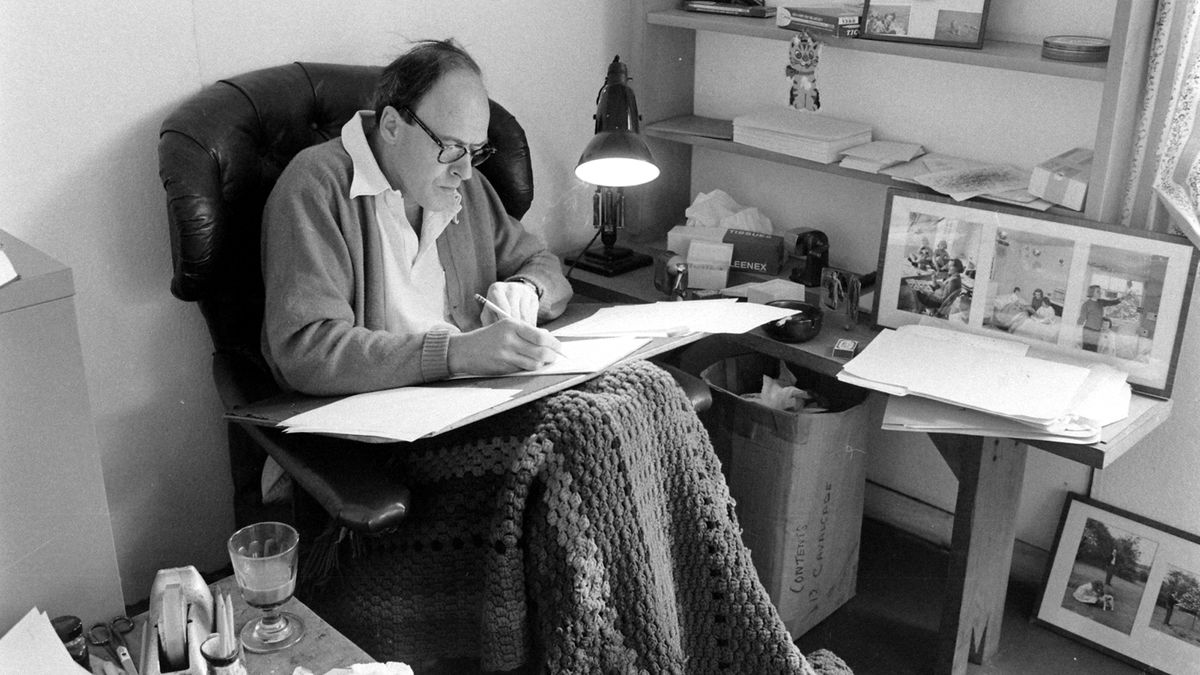

To escape the tragic heartbreaks, he eventually channeled his emotions into his writing, which evolved into the book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, published in 1964. “He wrote it over the four most difficult years of his life, between 1960 and 1964,” Sturrock said. But perhaps it was those feelings of helplessness that helped bring the tales — which he could control — to life.

“This sense of the magic, the genius of the inventor, I think is very clear in Wonka and also that sense of a really strong, dominant personality who could overcome anything,” Sturrock continued. “I think he poured himself into Wonka, and the more you know about the difficult circumstances of his own private life as he was writing the book, the more sympathetic and extraordinary Wonka becomes.”

In a show of its true lasting magic, the success of the book led to the opportunity for Dahl to write the screenplay for the 1971 film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory starring Gene Wilder. While Dahl died in 1990 of an infection at the age of 74, his sweetest story continues to charm audiences, like in the 2005 film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory starring Johnny Depp, the 2010 opera The Golden Ticket and the 2013 West End musical, which later made it to Broadway in 2017. And the story continues to grab headlines, like when Dahl’s widow Felicity told the BBC in 2017 that Charlie was originally meant to be African American.

But the greatest inspiration for Charlie and the Chocolate Factory may actually be found in what appears to be a cannonball that sat on the table of Dahl’s writing space, next to where he wrote the book. Upon closer inspection, it’s actually a wad of hundreds of chocolate foil wrappers, proving just how passionate he was about chocolate.

Thank you for reading this post Roald Dahl Wrote ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ During the ‘Most Difficult Years of His Life’ at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: