You are viewing the article Mary Todd Lincoln Shut Herself in the White House for Weeks After Abraham’s Death at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

April 14, 1865, got off to a far better start than most days in the White House Mary Todd Lincoln.

For years, Abraham Lincoln’s wife had been attacked in the press for her profligate spending, unladylike behavior and alleged Southern sympathies during the Civil War, with her misery compounded by the loss of her 11-year-old son, Willie, to typhoid fever in 1862. Now, the first lady’s burden clearly lifted by the recent surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, the Lincolns were able to enjoy a relaxing, romantic carriage ride before heading out for an evening at Ford’s Theatre.

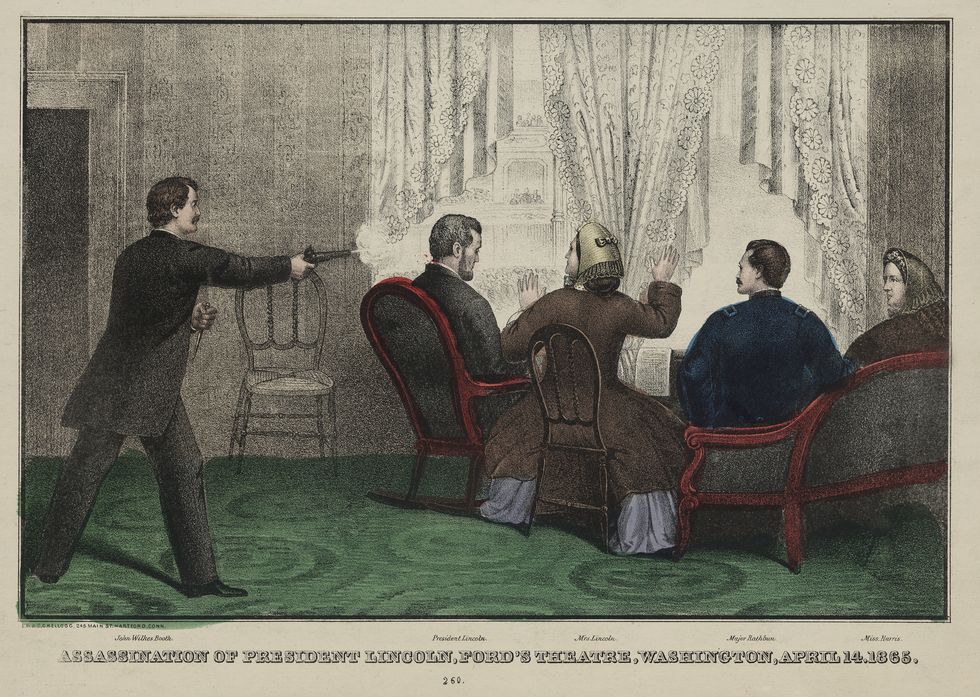

Sadly, it would be an all-too-brief moment of happiness before the day ended in unimaginable fashion, with Mary wailing over Abraham’s body following a point-blank gunshot to the back of the head by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth.

The first lady disturbed visitors with her despondency

The events that transpired that long night gave an indication of the grief that Mary was largely to endure alone. As the president lay dying in the Peterson House, Mary’s visible anguish proved too disturbing for the stoic, mostly male circle of advisers gathered, and Secretary of War William Stanton ordered her out of the room, denying her the chance to be with her husband in his final moments.

Upon returning to the White House a few hours later, Mary was unable to enter most of the mansion’s rooms without painful reminders of the man who walked its halls. She finally collapsed in a small spare bedroom and commenced what her dressmaker and confidante Elizabeth Keckly described as “the wails of a broken heart, the unearthly shrieks, the terrible convulsions.”

Mary did not surface for a viewing of the president’s coffin on April 18 nor for funeral services the following day, one of the few signs of life from behind her door coming when she sent word that the hammering of nails on the coffin platform reminded her of gunshots.

The select few allowed access to the widow included her sons Robert and Tad, close friends like Keckly and Dr. Anson Henry and the spiritualists who had provided consolation since Willie’s death a few years earlier. However, those who entered were alarmed by her condition, with one visitor describing her as “more dead than alive – broken by the horrors of that dreadful night as well as worn down by body sickness.”

Despite mourning her husband, Mary continued to be forceful with others

Amid her grief, Mary rediscovered her characteristic assertiveness upon learning that officials of the Lincolns’ former hometown of Springfield, Illinois, planned to bury Abraham in a cemetery in the middle of the city, his resting spot marked by a towering monument.

Mary quickly sent word of her insistence on a family plot in the quiet Springfield suburb of Oak Ridge, the sort of pastoral setting her husband would have preferred. The Springfield officials balked, as they had already sunk a considerable investment into the city plot, though they relented after she threatened to have the president’s body moved to a vault in Washington, D.C.

Mary also saved some of her ire for her husband’s successor. Sworn in shortly after Abraham’s death, Andrew Johnson gave the grieving widow space by setting up shop in the Treasury building. But he also neglected to pay a courtesy visit or send a note of sympathy, an affront Mary found inexcusable, and possibly fueled her accusation that he was somehow involved in the assassination.

READ MORE: What Abraham Lincoln Was Carrying in His Pockets the Night He Was Killed

She refused to consider moving to her old home in Springfield

In the meantime, the first lady’s mourning period in a home that was no longer hers stretched from days to weeks, her inertia in part stemming to her belief that she had nowhere to go.

This wasn’t entirely true: She remained the legal owner of the family’s old house in Springfield, and both her son Robert and Supreme Court Justice David Davis, administrator of Abraham’s estate, advised her that she lacked the finances to live anywhere else.

But Mary had already burned bridges in Springfield, her fight with city officials underscoring what was sure to be an unwelcome reception, and she didn’t want to be someplace where she would again be bombarded by memories her deceased husband. Against her advisers’ wishes, she settled on Chicago as the locale for post-White House life.

On May 23, five weeks after Abraham’s death and the same day a parade of veterans commemorated the Union victory in the nation’s capital, Mary finally departed the White House and boarded a train with Robert, Tad, Keckly and two guards. Clad in black, as she would be for the remaining 17 years of her life, she prepared for the 54-hour journey that lay ahead, hopeful that a new life in Chicago would somehow bring a respite from the pain.

Thank you for reading this post Mary Todd Lincoln Shut Herself in the White House for Weeks After Abraham’s Death at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: