You are viewing the article Marie Curie at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

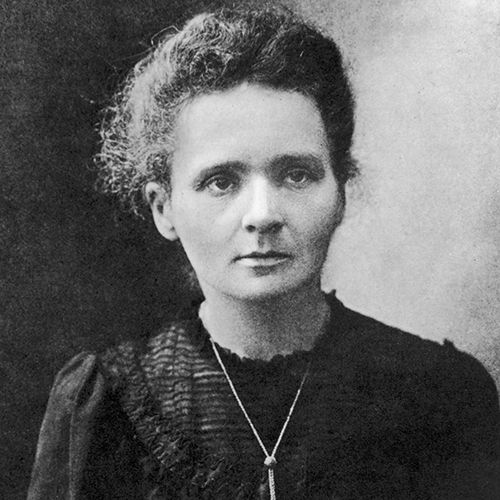

Marie Curie, one of the most revered female scientists in history, left an indelible mark on the world through her groundbreaking discoveries in the field of radioactivity. Revered for her unwavering dedication to both science and humanity, Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the only person to ever receive Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields. Her remarkable contributions not only reshaped our understanding of physics and chemistry but also altered perceptions about gender roles in academia and society at large. This introduction explores the life, achievements, and enduring legacy of Marie Curie, shedding light on her profound impact on the scientific community and the world as a whole.

(1867-1934)

Who Was Marie Curie?

Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the first person — man or woman — to win the award twice. With her husband Pierre Curie, Marie’s efforts led to the discovery of polonium and radium and, after Pierre’s death, the further development of X-rays. The famed scientist died in 1934 of aplastic anemia likely caused by exposure to radiation.

Early Life and Education

Maria Sklodowska, later known as Marie Curie, was born on November 7, 1867, in Warsaw (modern-day Poland). Curie was the youngest of five children, following siblings Zosia, Józef, Bronya and Hela.

Both of Curie’s parents were teachers. Her father, Wladyslaw, was a math and physics instructor. When she was only 10, Curie lost her mother, Bronislawa, to tuberculosis.

As a child, Curie took after her father. She had a bright and curious mind and excelled at school. But despite being a top student in her secondary school, Curie could not attend the male-only University of Warsaw. She instead continued her education in Warsaw’s “floating university,” a set of underground, informal classes held in secret.

Both Curie and her sister Bronya dreamed of going abroad to earn an official degree, but they lacked the financial resources to pay for more schooling. Undeterred, Curie worked out a deal with her sister: She would work to support Bronya while she was in school, and Bronya would return the favor after she completed her studies.

For roughly five years, Curie worked as a tutor and a governess. She used her spare time to study, reading about physics, chemistry and math.

In 1891, Curie finally made her way to Paris and enrolled at the Sorbonne. She threw herself into her studies, but this dedication had a personal cost: with little money, Curie survived on buttered bread and tea, and her health sometimes suffered because of her poor diet.

Curie completed her master’s degree in physics in 1893 and earned another degree in mathematics the following year.

Marriage to Pierre Curie

Marie married French physicist Pierre Curie on July 26, 1895. They were introduced by a colleague of Marie’s after she graduated from Sorbonne University; Marie had received a commission to perform a study on different types of steel and their magnetic properties and needed a lab for her work.

A romance developed between the brilliant pair, and they became a scientific dynamic duo who were completely devoted to one another. At first, Marie and Pierre worked on separate projects. But after Marie discovered radioactivity, Pierre put aside his own work to help her with her research.

Marie suffered a tremendous loss in 1906 when Pierre was killed in Paris after accidentally stepping in front of a horse-drawn wagon. Despite her tremendous grief, she took over his teaching post at the Sorbonne, becoming the institution’s first female professor.

In 1911, Curie’s relationship with her husband’s former student, Paul Langevin, became public. Curie was derided in the press for breaking up Langevin’s marriage, the negativity in part stemming from rising xenophobia in France.

Children

In 1897, Marie and Pierre welcomed a daughter, Irène. The couple had a second daughter, Ève, in 1904.

Irène Joliot-Curie followed in her mother’s footsteps, winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935. Joliot-Curie shared the honor with her husband, Frédéric Joliot, for their work on the synthesis of new radioactive elements.

In 1937, Ève Curie wrote the first of many biographies devoted to her famous mother, Madame Curie, which became a feature film a few years later.

Discoveries

Curie discovered radioactivity, and, together with her husband Pierre, the radioactive elements polonium and radium while working with the mineral pitchblende. She also championed the development of X-rays after Pierre’s death.

Radioactivity, Polonium and Radium

Fascinated with the work of Henri Becquerel, a French physicist who discovered that uranium casts off rays weaker than the X-rays found by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Curie took his work a few steps further.

Curie conducted her own experiments on uranium rays and discovered that they remained constant, no matter the condition or form of the uranium. The rays, she theorized, came from the element’s atomic structure. This revolutionary idea created the field of atomic physics. Curie herself coined the word “radioactivity” to describe the phenomena.

Following Curie’s discovery of radioactivity, she continued her research with her husband Pierre. Working with the mineral pitchblende, the pair discovered a new radioactive element in 1898. They named the element polonium, after Curie’s native country of Poland.

They also detected the presence of another radioactive material in the pitchblende and called that radium. In 1902, the Curies announced that they had produced a decigram of pure radium, demonstrating its existence as a unique chemical element.

Development of X-rays

When World War I broke out in 1914, Curie devoted her time and resources to help the cause. She championed the use of portable X-ray machines in the field, and these medical vehicles earned the nickname “Little Curies.”

After the war, Curie used her celebrity to advance her research. She traveled to the United States twice — in 1921 and in 1929 — to raise funds to buy radium and to establish a radium research institute in Warsaw.

Nobel Prizes

Curie won two Nobel Prizes, for physics in 1903 and for chemistry in 1911. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize as well as the first person—man or woman—to win the prestigious award twice. She remains the only person to be honored for accomplishments in two separate sciences.

Curie received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, along with her husband and Henri Becquerel, for their work on radioactivity. With their win, the Curies developed an international reputation for their scientific efforts, and they used their prize money to continue their research.

In 1911, Curie won her second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, for her discovery of radium and polonium. While she received the prize alone, she shared the honor jointly with her late husband in her acceptance lecture.

Around this time, Curie joined with other famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Max Planck, to attend the first Solvay Congress in Physics and discuss the many groundbreaking discoveries in their field.

How Did Marie Curie Die?

Curie died on July 4, 1934, of aplastic anemia, believed to be caused by prolonged exposure to radiation.

She was known to carry test tubes of radium around in the pocket of her lab coat. Her many years working with radioactive materials took a toll on her health.

Legacy

Curie made many breakthroughs in her lifetime. Remembered as a leading figure in science and a role model for women, she has received numerous posthumous honors. Several educational and research institutions and medical centers bear the Curie name, including the Curie Institute and Pierre and Marie Curie University (UPMC).

In 1995, Marie and Pierre’s remains were interred in the Panthéon in Paris, the final resting place of France’s greatest minds. Marie became the first and one of only five women to be laid to rest there. In 2017, the Panthéon hosted an exhibition to honor the 150th birthday of the pioneering scientist.

The story of the Nobel laureate was back on the big screen in 2017 with Marie Curie: The Courage of Knowledge, featuring Polish actress Karolina Gruszka. In 2018, Amazon announced the development of another biopic of Curie, with British actress Rosamund Pike in the starring role.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Marie Curie

- Birth Year: 1867

- Birth date: November 7, 1867

- Birth City: Warsaw

- Birth Country: Poland

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, in Physics, and with her later win, in Chemistry, she became the first person to claim Nobel honors twice. Her efforts with her husband Pierre led to the discovery of polonium and radium, and she championed the development of X-rays.

- Industries

- Science and Medicine

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Schools

- Sorbonne

- Nacionalities

- French

- Polish

- Interesting Facts

- In 1903 Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize.

- In 1911 Curie became the first person to win two Nobel Prizes.

- Curie’s daughter Iréne followed in her mother’s footsteps, winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935.

- Death Year: 1934

- Death date: July 4, 1934

- Death City: Passy

- Death Country: France

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn’t look right,contact us!

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Marie Curie Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scientists/marie-curie

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: October 8, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

QUOTES

- I believe that science has great beauty. A scientist in his laboratory is not a mere technician; he is also a child confronting natural phenomena that impress him as though they were fairy tales.

- One never notices what has been done; one can only see what remains to be done.

- In science, we must be interested in things, not in persons.

- All my life through, the new sights of nature made me rejoice like a child.

- In the education of children the requirement of their growth and physical evolution should be respected, and that some time should be left for their artistic culture.

- Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood.

- I was taught that the way of progress was neither swift nor easy.

- Life is not easy for any of us. But what of that? We must have perseverance and above all confidence in ourselves.

- You cannot hope to build a better world without improving the individuals.

- It is important to make a dream of life and a dream reality.

- There are sadistic scientists who hurry to hunt down errors instead of establishing the truth.

In conclusion, Marie Curie was an extraordinary scientist who made groundbreaking discoveries in the field of radioactivity. Her dedication, persistence, and intellect allowed her to overcome numerous obstacles and make significant contributions to the scientific community. Curie’s achievements not only helped advance our understanding of radioactivity but also paved the way for future scientific advancements in the fields of medicine and nuclear energy. Her determination and passion serve as an inspiration to aspiring scientists worldwide, reminding us that with the right mindset and commitment, anything is possible. Marie Curie’s impact on the world of science is undeniable, and her legacy will continue to inspire generations to come.

Thank you for reading this post Marie Curie at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. Marie Curie’s contribution to science

2. Marie Curie’s early life and education

3. Marie Curie’s discovery of radium and polonium

4. Marie Curie’s Nobel Prizes in Physics and Chemistry

5. Marie Curie’s research on radiation and its medical applications

6. Marie Curie’s role in World War I and her mobile radiography units

7. Marie Curie’s personal life and family

8. Marie Curie’s legacy and influence in the scientific community

9. Marie Curie’s struggles as a female scientist in the early twentieth century

10. Marie Curie’s research on radioactivity and its impact on modern science