You are viewing the article Langston Hughes’ Impact on the Harlem Renaissance at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

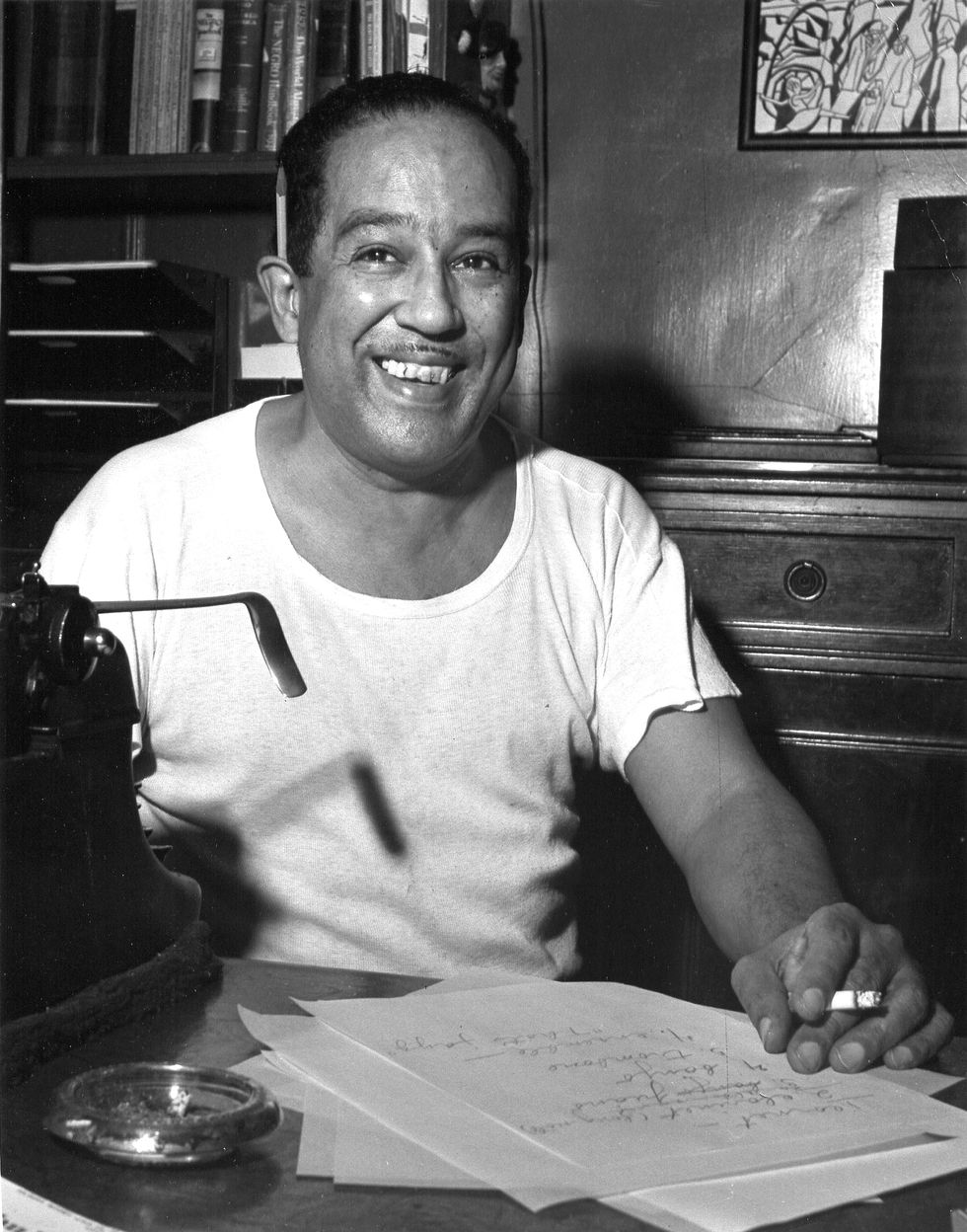

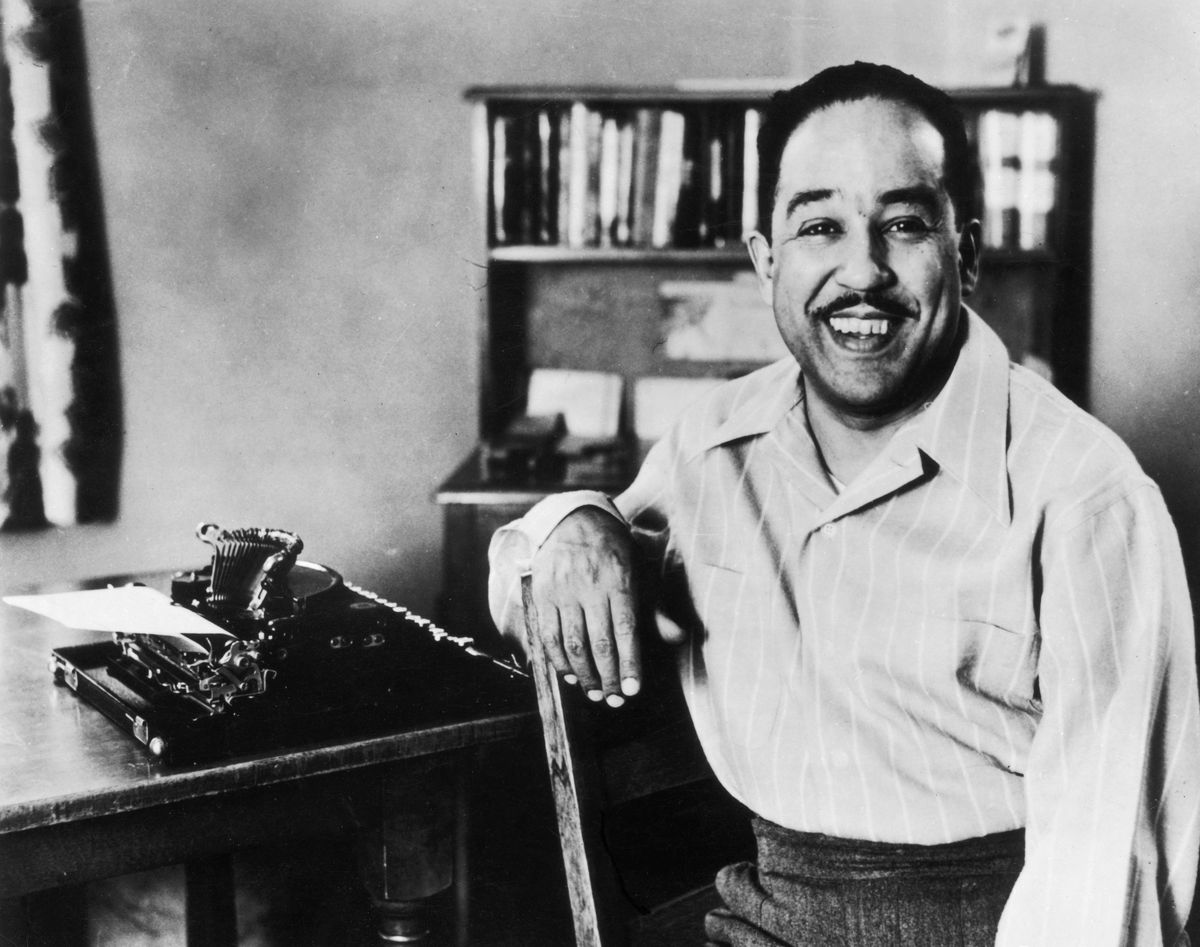

During the Harlem Renaissance, which took place roughly from the 1920s to the mid-’30s, many Black artists flourished as public interest in their work took off. One of the Renaissance’s leading lights was poet and author Langston Hughes.

Hughes not only made his mark in this artistic movement by breaking boundaries with his poetry, he drew on international experiences, found kindred spirits amongst his fellow artists, took a stand for the possibilities of Black art and influenced how the Harlem Renaissance would be remembered.

Hughes stood up for Black artists

George Schuyler, the editor of a Black paper in Pittsburgh, wrote the article “The Negro-Art Hokum” for an edition of The Nation in June 1926.

The article discounted the existence of “Negro art,” arguing that African-American artists shared European influences with their white counterparts, and were, therefore, producing the same kind of work. Spirituals and jazz, with their clear links to Black performers, were dismissed as folk art.

Invited to make a response, Hughes penned “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” In it, he described Black artists rejecting their racial identity as “the mountain standing in the way of any true Negro art in America.” But he declared that instead of ignoring their identity, “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual, dark-skinned selves without fear or shame.”

This clarion call for the importance of pursuing art from a Black perspective was not only the philosophy behind much of Hughes’ work, but it was also reflected throughout the Harlem Renaissance.

Some critics called Hughes’ poems “low-rate”

Hughes broke new ground in poetry when he began to write verse that incorporated how Black people talked and the jazz and blues music they played. He led the way in harnessing the blues form in poetry with “The Weary Blues,” which was written in 1923 and appeared in his 1926 collection The Weary Blues.

Hughes’ next poetry collection — published in February 1927 under the controversial title Fine Clothes to the Jew — featured Black lives outside the educated upper and middle classes, including drunks and prostitutes.

A preponderance of Black critics objected to what they felt were negative characterizations of African Americans — many Black characters created by whites already consisted of caricatures and stereotypes, and these critics wanted to see positive depictions instead. Some were so incensed that they attacked Hughes in print, with one calling him “the poet low-rate of Harlem.”

But Hughes believed in the worthiness of all Black people to appear in art, no matter their social status. He argued, “My poems are indelicate. But so is life.” And though many of his contemporaries might not have seen the merits, the collection came to be viewed as one of Hughes’ best. (The poet did end up agreeing that the title — a reference to selling clothes to Jewish pawnbrokers in hard times — was a bad choice.)

Hughes’ travels helped give him different perspectives

Hughes came to Harlem in 1921, but was soon traveling the world as a sailor and taking different jobs across the globe. In fact, he spent more time outside Harlem than in it during the Harlem Renaissance.

His journeys, along with the fact that he’d lived in several different places as a child and had visited his father in Mexico, allowed Hughes to bring varied perspectives and approaches to the work he created.

In 1923, when the ship he was working on visited the west coast of Africa, Hughes, who described himself as having “copper-brown skin and straight black hair,” had a member of the Kru tribe tell him he was a White man, not a Black one.

Hughes lived in Paris for part of 1924, where he eked out a living as a doorman and met Black jazz musicians. And in the fall of 1924, Hughes saw many white sailors get hired instead of him when he was desperate for a ship to take him home from Genoa, Italy. This led to his plaintive, powerful poem “I, Too,” a meditation on the day that such unequal treatment would end.

Hughes and other young Black artists formed a support group

By 1925 Hughes was back in the United States, where he was greeted with acclaim. He was soon attending Lincoln University in Pennsylvania but returned to Harlem in the summer of 1926.

There, he and other young Harlem Renaissance artists like novelist Wallace Thurman, writer Zora Neale Hurston, artist Gwendolyn Bennett and painter Aaron Douglas formed a support group together.

Hughes was part of the group’s decision to collaborate on Fire!!, a magazine intended for young Black artists like themselves. Instead of the limits on content they faced at more staid publications like the NAACP’s Crisis magazine, they aimed to tackle a broader, uncensored range of topics, including sex and race.

Unfortunately, the group only managed to put out a single issue of Fire!!. (And Hughes and Hurston had a falling out after a failed collaboration on a play called Mule Bone.) But by creating the magazine, Hughes and the others had still taken a stand for the kind of ideas they wanted to pursue going forward.

He continued to spread the word of the Harlem Renaissance long after it was over

In addition to what he wrote during the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes helped make the movement itself more well known. In 1931, he embarked on a tour to read his poetry across the South. His fee was ostensibly $50, but he would lower the amount, or forego it entirely, at places that couldn’t afford it.

His tour and willingness to deliver free programs when necessary helped many get acquainted with the Harlem Renaissance.

And in his autobiography The Big Sea (1940), Hughes provided a firsthand account of the Harlem Renaissance in a section titled “Black Renaissance.” His descriptions of the people, art and goings-on would influence how the movement was understood and remembered.

Hughes even played a part in shifting the name for the era from “Negro Renaissance” to “Harlem Renaissance,” as his book was one of the first to use the latter term.

Thank you for reading this post Langston Hughes’ Impact on the Harlem Renaissance at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: