You are viewing the article Joseph Stalin at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

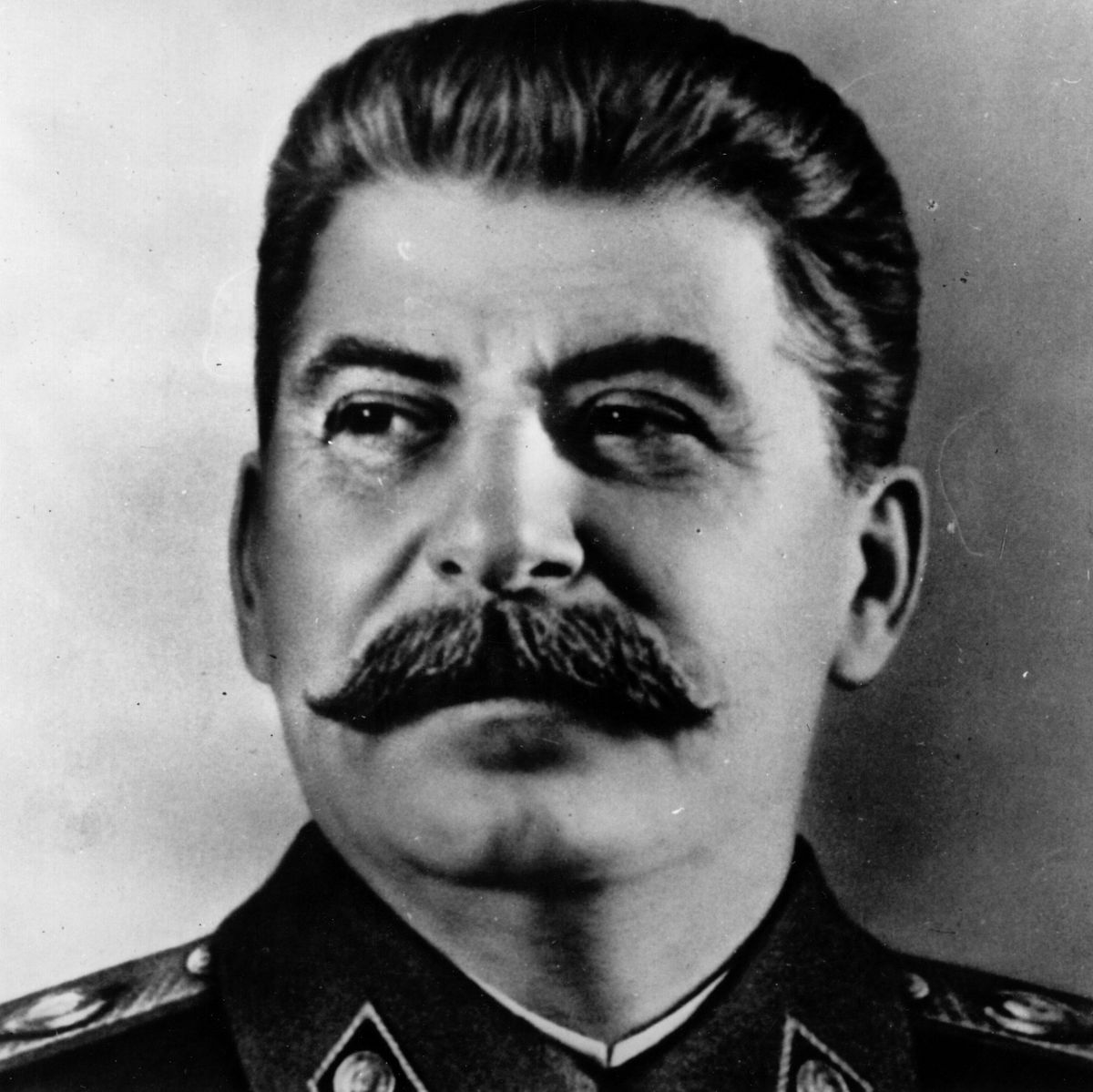

Joseph Stalin, born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili, was a Soviet politician and dictator who led the Soviet Union from the mid-1920s until his death in 1953. As one of the most influential and controversial figures of the 20th century, Stalin left an indelible mark on world history through his ruthless tactics, economic policies, and oppressive regime. Despite his notable role in transforming the Soviet Union into a global superpower, Stalin’s reign was characterized by violence, human rights abuses, and the deaths of millions of people. This introduction aims to provide a glimpse into the life and impact of Joseph Stalin, delving into his rise to power, policies, and the lasting consequences of his leadership.

(1878-1953)

Who Was Joseph Stalin?

Joseph Stalin rose to power as General Secretary of the Communist Party in Russia, becoming a Soviet dictator after the death of Vladimir Lenin. Stalin forced rapid industrialization and the collectivization of agricultural land, resulting in millions dying from famine while others were sent to labor camps. His Red Army helped defeat Nazi Germany during World War II.

Early Life

On December 18, 1879, in the Russian peasant village of Gori, Georgia, Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili – later known as Joseph Stalin – was born.

The son of Besarion Jughashvili, a cobbler, and Ketevan Geladze, a washerwoman, Stalin was a frail child. At age 7, he contracted smallpox, leaving his face scarred.

A few years later he was injured in a carriage accident which left arm slightly deformed (some accounts state his arm trouble was a result of blood poisoning from the injury).

The other village children treated him cruelly, instilling in him a sense of inferiority. Because of this, Stalin began a quest for greatness and respect. He also developed a cruel streak for those who crossed him.

Stalin’s mother, a devout Russian Orthodox Christian, wanted him to become a priest. In 1888, she managed to enroll him in church school in Gori. Stalin did well in school, and his efforts gained him a scholarship to Tiflis Theological Seminary in 1894.

A year later, Stalin came in contact with Messame Dassy, a secret organization that supported Georgian independence from Russia. Some of the members were socialists who introduced him to the writings of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin. Stalin joined the group in 1898.

Though he excelled in seminary school, Stalin left in 1899. Accounts differ as to the reason; official school records state he was unable to pay the tuition and withdrew. It’s also speculated he was asked to leave due to his political views challenging the tsarist regime of Nicholas II.

Stalin chose not to return home, but stayed in Tiflis, devoting his time to the revolutionary movement. For a time, he found work as a tutor and later as a clerk at the Tiflis Observatory. In 1901, he joined the Social Democratic Labor Party and worked full-time for the revolutionary movement.

Russian Revolution

In 1902, he was arrested for coordinating a labor strike and exiled to Siberia, the first of his many arrests and exiles in the fledgling years of the Russian Revolution. It was during this time that he adopted the name Stalin, meaning “steel” in Russian.

Though never a strong orator like Vladimir Lenin or an intellectual like Leon Trotsky, Stalin excelled in the mundane operations of the revolution, calling meetings, publishing leaflets and organizing strikes and demonstrations.

After escaping from exile, he was marked by the Okhranka, (the tsar’s secret police) as an outlaw and continued his work in hiding, raising money through robberies, kidnappings and extortion. Stalin gained infamy being associated with the 1907 Tiflis bank robbery, which resulted in several deaths and 250,000 rubles stolen (approximately $3.4 million in U.S. dollars).

In February 1917, the Russian Revolution began. By March, the tsar had abdicated the throne and was placed under house arrest. For a time, the revolutionaries supported a provisional government, believing a smooth transition of power was possible.

But in April 1917, Bolshevik leader Lenin denounced the provisional government, arguing that the people should rise up and take control by seizing land from the rich and factories from the industrialists. By October, the revolution was complete and the Bolsheviks were in control.

Communist Party Leader

The fledgling Soviet government went through a violent period after the revolution as various individuals vied for position and control.

In 1922, Stalin was appointed to the newly created office of general secretary of the Communist Party. Though not a significant post at the time, it gave Stalin control over all party member appointments, which allowed him to build his base.

He made shrewd appointments and consolidated his power so that eventually nearly all members of the central command owed their position to him. By the time anyone realized what he had done, it was too late. Even Lenin, who was gravely ill, was helpless to regain control from Stalin.

Great Purge

After Lenin’s death, in 1924, Stalin set out to destroy the old party leadership and take total control. At first, he had people removed from power through bureaucratic shuffling and denunciations.

Many were exiled abroad to Europe and the Americas, including presumed Lenin successor Leon Trotsky. However, further paranoia set in and Stalin soon conducted a vast reign of terror, having people arrested in the night and put before spectacular show trials.

Potential rivals were accused of aligning with capitalist nations, convicted of being “enemies of the people” and summarily executed. The period known as the Great Purge eventually extended beyond the party elite to local officials suspected of counter-revolutionary activities.

Reform and Famine

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Stalin reversed the Bolshevik agrarian policy by seizing land given earlier to the peasants and organizing collective farms. This essentially reduced the peasants back to serfs, as they had been during the monarchy.

Stalin believed that collectivism would accelerate food production, but the peasants resented losing their land and working for the state. Millions were killed in forced labor or starved during the ensuing famine.

Stalin also set in motion rapid industrialization that initially achieved huge successes, but over time cost millions of lives and vast damage to the environment. Any resistance was met with swift and lethal response; millions of people were exiled to the labor camps of the Gulag or were executed.

World War II

As war clouds gathered over Europe in 1939, Stalin made a seemingly brilliant move, signing a nonaggression pact with Germany’s Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party.

Stalin was convinced of Hitler’s integrity and ignored warnings from his military commanders that Germany was mobilizing armies on its eastern front. When the Nazi blitzkrieg struck in June 1941, the Soviet Army was completely unprepared and immediately suffered massive losses.

Stalin was so distraught at Hitler’s treachery that he hid in his office for several days. By the time Stalin regained his resolve, German armies occupied all of the Ukraine and Belarus, and its artillery surrounded Leningrad.

To make matters worse, the purges of the 1930s had depleted the Soviet Army and government leadership to the point where both were nearly dysfunctional. After heroic efforts on the part of the Soviet Army and the Russian people, the Germans were turned back at the Battle of Stalingrad in 1943.

By the next year, the Soviet Army was liberating countries in Eastern Europe, even before the Allies had mounted a serious challenge against Hitler at D-Day.

Stalin and the West

Stalin had been suspicious of the West since the inception of the Soviet Union, and once the Soviet Union had entered the war, Stalin had demanded the Allies open up a second front against Germany.

Both British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt argued that such an action would result in heavy casualties. This only deepened Stalin’s suspicion of the West, as millions of Russians died.

As the tide of war slowly turned in the Allies’ favor, Roosevelt and Churchill met with Stalin to discuss postwar arrangements. At the first of these meetings, in Tehran, Iran, in late 1943, the recent victory in Stalingrad put Stalin in a solid bargaining position. He demanded the Allies open a second front against Germany, which they agreed to in the spring of 1944.

In February 1945, the three leaders met again at the Yalta Conference in the Crimea. With Soviet troops liberating countries in Eastern Europe, Stalin was again in a strong position and negotiated virtually a free hand in reorganizing their governments. He also agreed to enter the war against Japan once Germany was defeated.

The situation changed at the Potsdam Conference in July 1945. Roosevelt died that April and was replaced by President Harry S. Truman. British parliamentary elections had replaced Prime Minister Churchill with Clement Attlee as Britain’s chief negotiator.

By now, the British and Americans were suspicious of Stalin’s intentions and wanted to avoid Soviet involvement in a postwar Japan. The dropping of two atomic bombs in August 1945 forced Japan’s surrender before the Soviets could mobilize.

Stalin and Foreign Relations

Convinced of the Allies’ hostility toward the Soviet Union, Stalin became obsessed with the threat of an invasion from the West. Between 1945 and 1948, he established Communist regimes in many Eastern European countries, creating a vast buffer zone between Western Europe and “Mother Russia.”

Western powers interpreted these actions as proof of Stalin’s desire to place Europe under Communist control, thus formed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to counter Soviet influence.

In 1948, Stalin ordered an economic blockade on the German city of Berlin, in hopes of gaining full control of the city. The Allies responded with the massive Berlin Airlift, supplying the city and eventually forcing Stalin to back down.

Stalin suffered another foreign policy defeat after he encouraged North Korean Communist leader Kim Il Sung to invade South Korea, believing the United States would not interfere.

Earlier, he had ordered the Soviet representative to the United Nations to boycott the Security Council because it refused to accept the newly formed Communist People’s Republic of China into the United Nations. When the resolution to support South Korea came to a vote in the Security Council, the Soviet Union was unable to use its veto.

How Many People Did Joseph Stalin Kill?

It’s estimated that Stalin killed as many as 20 million people, directly or indirectly, through famine, forced labor camps, collectivization and executions.

Some scholars have argued that Stalin’s record of killings amount to genocide and make him one of history’s most ruthless mass murderers.

Death

Though his popularity from his successes during World War II was strong, Stalin’s health began to deteriorate in the early 1950s. After an assassination plot was uncovered, he ordered the head of the secret police to instigate a new purge of the Communist Party.

Before it could be executed, however, Stalin died on March 5, 1953. He left a legacy of death and horror, even as he turned a backward Russia into a world superpower.

Stalin was eventually denounced by his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, in 1956. However, he has found a rekindled popularity among many of Russia’s young people.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Joseph Stalin

- Birth Year: 1878

- Birth date: December 18, 1878

- Birth City: Gori, Georgia

- Birth Country: Russia

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Joseph Stalin ruled the Soviet Union for more than two decades, instituting a reign of death and terror while modernizing Russia and helping to defeat Nazism.

- Industries

- War and Militaries

- World Politics

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- Schools

- Tiflis Theological Seminary

- Church school (Gori, Georgia, Russian Empire)

- Death Year: 1953

- Death date: March 5, 1953

- Death City: Moscow

- Death Country: Russia

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Joseph Stalin Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/joseph-stalin

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 4, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

QUOTES

- History shows that there are no invincible armies.

- I believe in one thing only, the power of human will.

- It is enough that the people know there was an election. The people who cast the votes decide nothing. The people who count the votes decide everything.

- In the Soviet army, it takes more courage to retreat than advance.

In conclusion, Joseph Stalin was a complex and controversial figure in history. While there is no denying his significant role in transforming the Soviet Union into a major global power, his methods and policies were often ruthless and resulted in immense suffering for millions of people. Stalin’s oppressive regime, characterized by mass purges, forced collectivization, and widespread persecution, led to the death and displacement of countless individuals. Despite his achievements in industrialization, modernization, and the defeat of Hitler in World War II, Stalin’s legacy remains marred by the authoritarian nature of his rule and the violations of human rights under his regime. The debate surrounding Stalin’s leadership and his contributions to the Soviet Union continue to this day, as historians grapple with the complexities of evaluating his actions and their long-term consequences.

Thank you for reading this post Joseph Stalin at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. “Early life and upbringing of Joseph Stalin”

2. “Political career and rise to power of Joseph Stalin”

3. “Joseph Stalin’s role in the Russian Revolution”

4. “Collectivization and industrialization under Joseph Stalin”

5. “Purges and Great Terror during Joseph Stalin’s reign”

6. “Joseph Stalin’s role in World War II”

7. “Stalin’s Five-Year Plans and their impact on the Soviet Union”

8. “Stalin’s cult of personality and propaganda”

9. “Stalin’s policies towards religion and atheism in the Soviet Union”

10. “Assessment of Joseph Stalin’s legacy and impact on the Soviet Union”