You are viewing the article John Brown and Frederick Douglass Had a Complicated Friendship at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

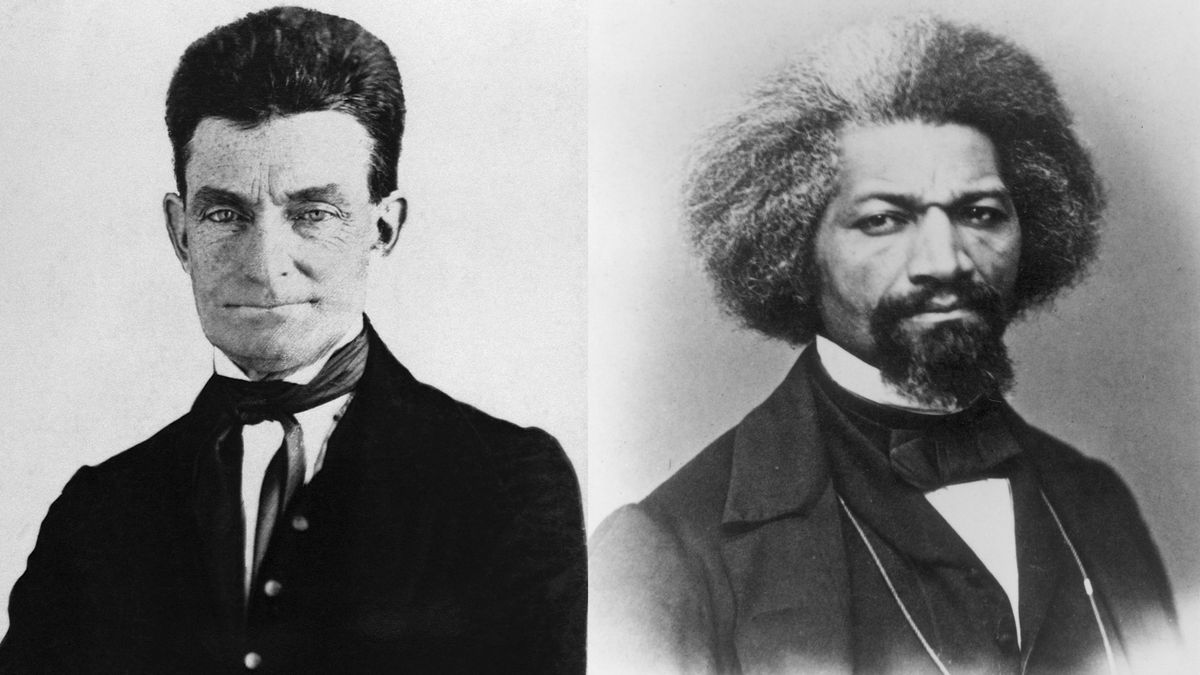

The inaugural meeting of two of the 19th century’s most famous abolitionists, Frederick Douglass and John Brown, took place at Brown’s home in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1847.

Douglass was already widely known for his enslaved upbringing and escape from captivity in the late 1830s, his account captured in 1845’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, and frequently rehashed in his public speeches.

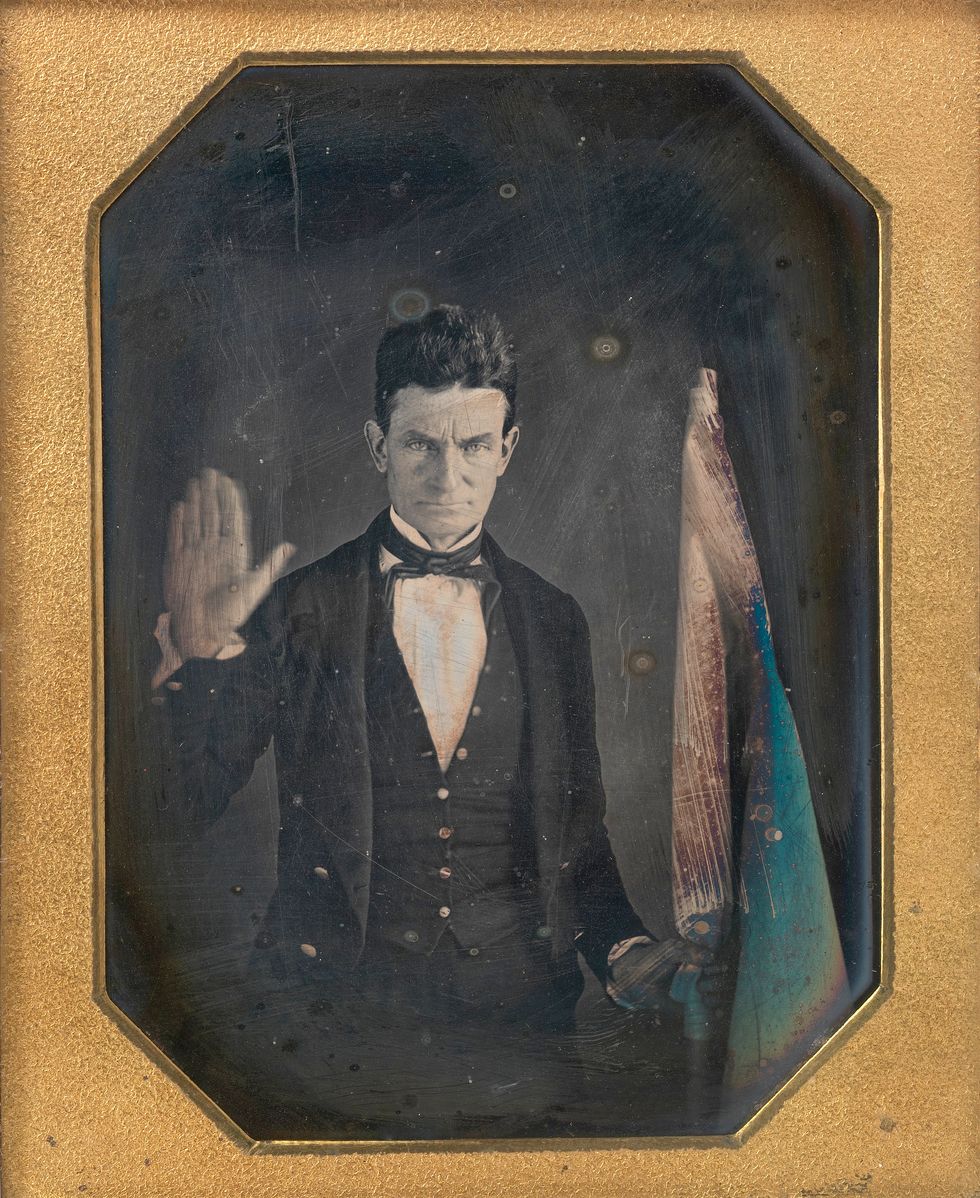

Yet it was Brown, a white man with a record of failed business interests and unyielding religious conviction, who seemingly came off as the one more determined to end the cruel institution of slavery that day.

Brown impressed Douglass with an early plan to free the enslaved

As he recalled in 1881’s Life and times of Frederick Douglass, Brown immediately impressed his guest with his “lean, strong and sinewy build” and the way “his children observed him with reverence.”

But it was Brown’s impassioned words that made the biggest mark, as he spoke of a plan to free the enslaved and squirrel them to freedom through the Alleghany Mountains.

His measured responses to Douglass’ questions showed he had given the matter careful thought. Armed men would be stationed at strategic checkpoints, he explained, from where they would slip down to towns to rally the enslaved and acquire provisions. And even if authorities managed to corner them, what better way to die than for such a noble cause?

Douglass was then a proponent of William Lloyd Garrison’s “non-resistance” form of abolitionism, but he began to reassess his beliefs after the night at Brown’s home. “While I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful of its peaceful abolition,” he wrote. “My utterances became more and more tinged by the color of this man’s strong impressions.”

Douglass frequently hosted Brown at his New York home

By the mid-1850s, Brown had become a national figure in his own right for his involvement in the violent “Bleeding Kansas” border conflicts, his actions celebrated by those who felt that slavery would only end through bloodshed. “I met him often during this struggle,” Douglass wrote, “and all I saw of him gave me a more favorable impression of the man, and inspired me with a higher respect for his character.”

Brown frequently stayed with Douglass during his trips back east to acquire money and arms during these years, one such visit captured by their joint letter to Brown’s wife in January 1858.

But despite his own heightened militancy, Douglass believed in the importance of political action to bring an end to slavery, placing him at odds with the increasing radicalism of Brown. The two men joined other abolitionist leaders at the Detroit home of William Webb in March 1859 but were unable to resolve the stalemate over their differing views.

Douglass refused to join Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid

Brown and Douglass met for the final time at a quarry near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in August 1859. This time, Brown presented the full scope of his plan to capture the federal armory at the Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and arm the enslaved for a major insurrection.

In Douglass’ recollection, Brown brushed off the warning that he was “going into a perfect steel trap” from which “he would never get out alive” and pressed forward with the attempt to recruit his friend: “When I strike the bees will begin to swarm, and I shall want you to help hive them.”

Whether it was due to “my discretion or my cowardice,” Douglass wrote, he declined to join what became the ill-fated Harpers Ferry raid on October 16, 1859 – nearly every member of the inciting party was either captured or killed, and Brown was hanged on December 2.

There is some dispute about whether Douglass’ version of events is accurate. One of Brown’s captured men, John E. Cook, claimed that the orator had backed out of a promise to bring more men to the raid. And Brown, who drew praise for refusing to implicate associates while awaiting his death sentence, reportedly complained to a friend about the “great opportunity lost” at Harpers Ferry, adding, “that we owe to the famous Mr. Frederick Douglass.”

The accusations prompted Douglass to defend himself in an October 31 letter to the Rochester Democrat and American, in which he insisted that he “never made a promise” to join the raid and that the “taking of Harpers Ferry was a measure never encouraged by my word or by my vote.” Regardless, he knew he was in a world of trouble for his public ties to a man being tried for treason, and by November he had set sail for England.

READ MORE: John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry

Douglass invoked Brown as a martyr to the cause

Returning the following summer to a country on the cusp of civil war, Douglass realized the value of invoking Brown as a martyr for anti-slavery efforts and as a recruiting tool for Union soldiers.

His mission accomplished with the Union victory, Douglass later celebrated his fallen friend through a speech delivered numerous times, including at Harpers Ferry’s Storer College in 1881, in which he depicted the armory raid as a “thunder clap” that sparked a morally decaying nation into action.

“When John Brown stretched forth his arm, the sky was cleared,” he declared in the speech’s powerful conclusion. “The time for compromises was gone, and to the armed hosts of freedom, standing above the chasm of a broken Union, was committed the decision of the sword. … and thus made her own, and not John Brown’s, the lost cause.”

Thank you for reading this post John Brown and Frederick Douglass Had a Complicated Friendship at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: