You are viewing the article Is a dog crate really a den? How this very American practice took off — WHYY at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Is a dog crate really a den? How this very American practice took off

Dog crating has become a normal part of pet ownership. But how did the idea that dogs see them as dens get started and where’s the science? How long is too long in a crate?

Listen 14:49

Studio shot of chocolate labrador in cage. (Photo by: Tetra Images/AP Images)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

I’ve wanted a dog for a long time. But first parents stood in the way, then roommates. Now that I have my own place — the only thing giving me pause is the dog crate.

I grew up in West Virginia, where dogs could have the run of a big yard or a whole house. It wasn’t until I moved to the city — Philadelphia in this case — that I first heard of a dog crate.

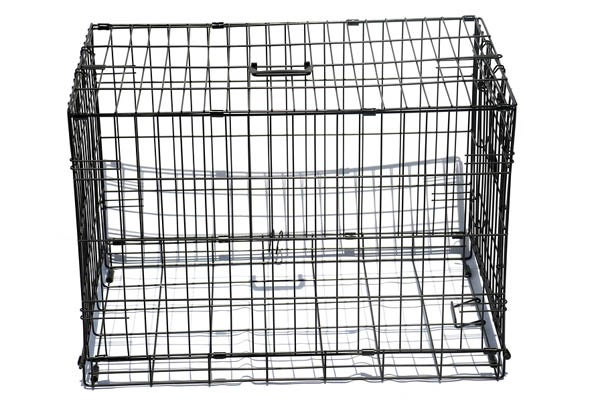

Dog ownership is different in the city, homes are smaller — we have alleyways instead of yards. And a lot of urban dog owners would look to these crates — essentially, wire cages big enough for the dog to stand and turn around in — to keep them from tearing up their living rooms.

JR Rogers at the Morris Animal Refuge tells me it’s a normal part of dog ownership here, but things don’t always go smoothly.

“Sometimes they may not be used to being crate trained,” he said. “They may try to hurt themselves — abuse themselves by biting the wires of the cage and cutting their gums because they’ve never been crate trained before.”

Most of the dogs at the shelter, he tells me, have been adopted and returned — some of them multiple times. Some bite, some hate the cat, or the kids. Another big reason: the dog doesn’t take to the dog crate.

Crate training

Crate training at its most basic, means keeping a puppy in one of these things for house breaking. The idea is they’ll learn to hold it rather than soil a confined space. But crating is also widely used with adult dogs basically to keep them from destroying stuff when left alone.

Annalise Curtin knows about all this. She’s worked as a dog trainer for a major chain. She says the crate is good for both the owner, and for the dog.

“It’s the first thing we teach, and [that’s] regardless of how old the dog is because you need the crate because it’s their safe space,” she said.

But all the guidelines I could find about how long to use a crate were vague. Basically, no more than four hours for a puppy, less than all day and night for an adult. But I know folks that use them when they’re at work or at school. So I ask Curtin about 8-hours, a full work day, is that ok?

“It’s totally fine,” she said. “As long as the crate is introduced properly. If they had separation anxiety and were freaking out in the crate, then they need to see a trainer because you have a risk of the dog injuring itself.”

I called a bunch of other trainers as well, they all told me this exact same thing: with proper training even an 8-hour work day is fine. The crate is actually calming, tapping into something natural for dogs.

“They’re den animals. It allows them to just relax and feel safe. It’s somewhere for them to go,” Curtin said. “Wild wolves hung out in caves and dens, it’s just in them.”

She’s referring to what’s typically called a “denning instinct.”

It’s the idea that dogs seek out confined spaces and make dens out of them, like their wolf ancestors. The denning instinct pops up all over. Popular trainers on TV and online talk about it all the time. It’s in the very first line of The Humane Society’s dog crating page in the U.S.

But the strange thing is, even though I kept running into it, I could never nail down where the denning instinct idea comes from, what study, whose research?

Dog vs. wolf

Carlo Siracusa, a veterinarian and behaviorist at the University of Pennsylvania, hesitated to answer when I asked him.

He told me it’s true wolves have a denning instinct. But the idea that dogs have one too? He says that comes from pretty flawed science — old observational studies.

“The majority of them were done in the 70s or earlier. They studied dogs and wolves in captivity, starting from the assumption that because they are closely related species and one is the ancestor of the other, they were in some way comparable,” he said.

Researchers noticed something big. There was constant aggressive, competition, it appeared to be the defining behavior in both in wolves and in dogs.

“Aggression [seemed to be] part of their regular way of communicating, so the whole dominance thing came out,” he said.

If you’ve ever heard a dog expert talk about alpha dogs or pack leader or whatever, this is where that comes from.

This competitive aggression, was the common thread that tied dogs and wolves together in the minds of some researchers and trainers. They figured if dogs and wolves shared this core trait— they probably shared a bunch of other behaviors. Denning — being one of them.

But all this aggression wasn’t actually natural. Siracusa says it was just the result of the stress of captivity.

“It’s like looking at the show ‘Big Brother’ to study human behavior,” Siracusa said.

“Big Brother”is a reality show where contestants are confined to a house, filmed 24/7 — with lots of drama and fights.

“But of course this doesn’t happen if you can just leave,” Siracusa said.

Wolf packs in nature are actually fairly peaceful, he said, because they’re usually family, blood related.

“So first off what we thought we knew about wolves was wrong,” he said.

And with more research on feral and semi-feral dog populations, the gulf between wolf and dog behavior grew much wider, in the 80s and 90s.

“We learned that they are two different species,” he said. “They don’t do the same thing and they actually don’t do the same thing well.”

That’s true for denning. Dogs don’t do it on a regular basis. Mama dogs will den briefly only right after pups are born, and male dogs just can’t be bothered at all.

“They are like, ‘I did my job, I’m out of here,” said Siracusa.

But by the time all this was coming out, the older, flawed ideas of wolf-dog similarities and denning were already widespread.

A trash bin becomes a dog crate

Media mentions of denning first start cropping up in the 80s — in a syndicated newspaper column called “The Family Pet.”

It recommends dog crates for behavior issues. One column has instructions to write to an education fund for more info. It looks like it’s linked to a poodle breeding group. They put out this pamphlet called “A Pet Owners Guide To The Dog Crate.”

It’s unclear who actually funded it, the author passed away. It reads:

“CRUELTY – OR KINDNESS? As The Pet Owner Sees It: “It’s like a jail – it’s cruel – I’d never put MY dog in a cage like that!” If this is your first reaction to using a crate, you are a very typical pet owner.”

And you’d be wrong typical pet owner in the 80s, the pamphlet reads, because:

“If your dog could talk, He would tell you that the crate helps to satisfy the “den instinct” from his den dwelling ancestors and relatives, and that he is not afraid or frustrated when closed in. He would further admit that he is actually much happier and more secure having his life controlled and structured by human beings – and would far rather be prevented from causing trouble than be punished for it later.”

This pamphlet talks about dog crating as already long trusted by breeders and dog pros. It could be part of the seed that got typical dog owners to start using them at home. Pet training professionalized in the 90s, and early 2000s — some big names used crates — some on TV, and later online.

I spoke with Ian Dunbar, one veterinarian and big name in early training circles, who advocated for crate training. But, he says, the modern hours-long crating of adult dogs is never what he intended. He says crate training is useful as a tool “mainly to teach household manners to young puppies with the idea that they then get to enjoy full run of the house and garden … for life.”

I also talked to a big crate maker, Midwest Homes For Pets, to track when sales started taking off. They actually started as a metal works company.

Tara Whitehead, a spokesperson, says they also used to make wire rubbish bins for trash burning. Then In the 50s, the company caught wind some guy in Detroit was buying these bins in bulk, using them to keep dogs.

“I’m not sure what his industry was,” she said. “I don’t know if he was you know, a breeder, or rescue, or just a guy that had a lot of dogs.”

The company tweaked the design of their bin, made it into a crate. The Sears catalogue picked it up in the 60s. By the mid 80s they were selling so many they created a separate crate-focused business.

And today?

“We’re doing more and more sales year over year,” she said. “It’s not falling down. It doesn’t get affected by recession.”

Their most recommended product is an adult-sized crate with dividers you remove as the dog grows from puppy into old age.

Only in America

Market analysts tell me about more than a third of all dog owners have a dog crate. Or more specify, a third of all American dog owners.

Another reason I wanted to talk to Carlo Siracusa is because he’s from Sicily. He read me a recently adopted Italian animal welfare law.

“It says that the space that an animal must have, it’s a minimum of 20 square meters,” he said.

That’s 215 square feet — the size of a large living room. A dog crate just has to be big enough for the animal to stand, and turn around.

“The difference is huge,” he said.

And it’s not just Italians. Siracusa has worked as a veterinarian all over Europe. He says crating just wasn’t a thing. This is true also in Australia. In Sweden, it’s actually outlawed.

Emma Almquist is a Swedish trainer. She recalls only ever reading about it in American pet books.

“I read in those books that you could teach your dog to go in a crate and, feel happy in the crate and sleep in the crate. And I was like, ‘yeah, okay. I guess, uh, that’s nice, but why?” she said.

The whole idea was baffling. She says owners in Sweden are expected to devout months to puppy proofing their homes and training instead of looking to a crate.

“So I didn’t really understand why?” she said.

Dog crating is nearly uniquely American, at least as a routine part of dog ownership.

Siracusa says he thinks part of it is convenience, and this American idea that if you want a dog, it’s your right to have one.

“Here it’s far less common for someone to tell another person: ‘Maybe you should not have a dog,’ Right? Many people will get offended, will say you are being judgmental,” he said. “But it’s very common in Europe that people will say ‘I don’t think you can get a dog. Like you have a crazy life.’”

He says even if you make them cozy, these crates are not dens. They come with locks.

“Let’s say a dog is afraid of noises, right? And there is a sudden noise and they get scared, then they cannot run away,” he said. “Or even something as simple as not just running and hiding, but just running around to dissipate your anxiety. It’s something that we do continuously. We humans, we pace when we are nervous. Some dogs like to do the same.”

He says not having control over your environment can be a big source of stress for dogs, just like for humans.

But he doesn’t say never use a crate. Or even never leave a dog in a crate when you go to work. Instead, he says you have to always interrogate, ‘are you doing this for your dog or for you? How is this member of your family experiencing all this?’

Love is not enough, dogs need our presence

“Our love to animals is not enough,” he said. “We might love animals, but if our condition is not enough, we might think is my love enough for that creature? [It] probably is not.”

He tells me I can really and truly love my pet with all heart, “but this love does not necessarily correspond to empathy.”

Siracusa stresses something else about the crate and dog ownership.

He says the crate, shouldn’t be the rule, the norm, and that’s not just because it’s small. You can leave a dog alone in a huge backyard or give it the run of the house. But more than space, dogs need our presence. They need us.

“What we have done with selection, we have twisted this sociability of dogs and oriented towards humans,” he said.

Through purposeful domestication. We chose dogs that loved us the most, that wanted to be near us the most, generation after generation, for thousands of years.

“We have created an animal that is very dependent on us, [depends on us] to pee, to poop, to eat, to do anything,” he said.

Dogs need us, humans, we made sure of that. Some studies show they prefer us, even over other dogs.

Siracusa says with this in mind there’s a danger the crate can become an excuse: To stay out later, to take your time getting home from this errand or that. I can end up tricking myself into thinking ‘my dog’s in a crate, it’s his den, he likes it, and, well, it’s locked. Not like he can tear up the couch.’

‘Just don’t put the dog down’

I took all this to Annalise Curtin, the trainer I spoke with earlier. I told her none of this is real, denning, alpha pack leader. I told her about Italy and Sweden.

But she tells me there’s something else at stake.

“A lot of the dogs I trained were going to be put down,” Curtain said.

Vets and trainers would tell owners their troublesome pets were out of options.

“And they’re like, ‘oh, there’s nothing else you can do. You have to put this dog down.’ So I was working with dogs who, literally, I was their last resort,” she said.

Some dogs just didn’t learn with treats or clicker training. In these cases the crate was the only thing that kept them from destroying the house — the only thing that worked.

“My main thing is just don’t put the dog down if it doesn’t want the treat,” she said. “I mean that’s just what kills me.”

Curtin doesn’t train anymore, part of it, she says, it got too heartbreaking. One owner admitted to her, he wished he could get rid of his dog, just start over with a new one that was less of a hassle.

So maybe the crate can do some good, make dogs easier for us, and maybe that keeps some from getting returned to Rogers at the Morris Animal Refuge, or worse, to an overflowing kill shelter.

I still really want a dog, but crate or no crate, what’s clear now is a dog is a bigger commitment than I thought, maybe more than a lot of us think. And I’m not there yet.

Back at the Morris Animal Refuge, I did linger a bit in the cat room on my way out.

I may just head back for another look.

Editor’s note: In a previous version of this article Carlo Siracusa’s name was misspelled. It has since been corrected.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Thank you for reading this post Is a dog crate really a den? How this very American practice took off — WHYY at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: