You are viewing the article Inside the Long-Forgotten JFK Inaugural Gala at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

On the night before John F. Kennedy made history as America’s youngest elected president — as well as its first Catholic one — a star-studded bash, hosted by Frank Sinatra, helped usher in what many hoped would be a new era in American history. But the event also revealed the deep racial divisions that still gripped much of the nation.

The Kennedy family had a long fascination with Hollywood

The family patriarch, Joseph Kennedy Sr., made his fortune in banking and on Wall Street, where his business acumen and ruthlessness saw him frequently skirting lax laws to his benefit.

By the mid-1920s, the East Coast-based Joseph had turned his attention West, drawn to the glamour — and business opportunities — of the film industry. In 1926 he led a group of investors who purchased FBO studios, setting out to become a media mogul. But within a few years, Joseph’s L.A. sojourn was over, and while many of those he had advised were left deeply in debt, Joseph had pocketed millions of dollars, which helped fund the next stage in his endlessly ambitious journey — politics.

Joseph’s Hollywood years, however, left a deep impression on his children, who like many other Americans harbored an infatuation with entertainers. His daughter, Patricia, married British-born actor Peter Lawford. And as his son John’s political star began to rise, he became close with a number of entertainers, many of whom he met through Lawford, including a rumored affair with Marilyn Monroe and a friendship with one of America’s most popular singers and actors — Sinatra.

READ MORE: Inside John F. Kennedy and Frank Sinatra’s Powerful Friendship

Sinatra was as fascinated with politics and power as the Kennedys were with Hollywood and glamour

A lifelong Democrat, Sinatra had been an ardent campaigner dating back to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidency, and he eagerly threw himself into getting young John elected.

John’s intelligence, wealth, good looks and cool demeanor, along with his energetic and attractive family, garnered him support throughout much of the entertainment industry, who, along with Sinatra, threw fundraisers, performed at rallies and helped organize for the Kennedy campaign. And while Joseph had a checkered history when it came to race, both Black and white entertainers lined up to support his son, including many who hoped John would tread a far more liberal path with regards to civil rights.

They were elated when John defeated Vice President Richard Nixon in November 1960. Sinatra, who rightly assumed that he had played an important role in JFK’s victory, hatched a plan to bring the worlds of politics and entertainment together by creating an inaugural gala to be held on the eve of John’s inauguration.

Sammy Davis Jr.’s relationship with a white woman proved politically problematic for the Kennedys

Like Sinatra and the rest of his Hollywood pals, Sammy Davis Jr. threw his support behind JFK. A singer, actor and dancer who’d got his start in show business when he was a toddler, Davis succeeded during an era of deep racial prejudice and discrimination, bristling at how white audiences openly adored him while he was on the stage. However, Davis was also criticized by many in the Black community for his willingness to play to what they considered racist stereotypes.

Throughout the 1960 campaign, Davis’ personal life was in the headlines, thanks to his romance with white actress May Britt. When the couple announced their engagement in June, the reaction was vicious. In an era when interracial marriages were legally prohibited in dozens of states (the Loving v. Virginia U.S. Supreme Court decision striking down these laws was still several years away), Davis and Britt were pilloried. Britt’s studio contract was canceled and the couple received death threats.

When Davis appeared alongside other entertainers at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles that summer, he was loudly booed — and deeply wounded. The Kennedy campaign, largely funded and closely controlled by Joseph, grew fearful of the impact Davis’ notoriety might have on the campaign, thanks in large part to the racist, anti-segregationist, anti-miscegenation views of a large swath of Southern Democrats, without which JFK would lose the election. Davis was reportedly pressured to delay his marriage until after the election, and the couple finally wed in mid-November, just days after JFK’s victory.

Davis was invited — and then disinvited — from Sinatra’s gala event

Sinatra pulled together the cream of the crop for the bash. It was a curious mix of pop culture luminaries, featuring a mix of entertainers from Broadway, Hollywood and beyond, including Bette Davis, Laurence Olivier, Milton Berle, Gene Kelly, Jimmy Durante, Ethel Merman (despite her avowed support for the Republican Party) and many others. Conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein led the orchestra.

There were also a number of Blacks slated to perform, including Mahalia Jackson, Sidney Poitier, Ella Fitzgerald, Harry Belafonte and Nat King Cole. Davis, one of Sinatra’s closest friends at the time, made plans to attend. But just days before, he was told he was out. It’s believed it was Joseph, who was bankrolling the gala, who made the brutal call (despite the fact that Cole, who had also married a white woman, was allowed to perform).

Davis was crushed by the slight, and the slight upset the other Black performers, including Belafonte, who told Vanity Fair magazine, “ It was one of those moments where not only was Frank not happy about it, the rest of us were put up against a moment where [we thought], How do we let this slide?… And Sammy not being there was a loss.”

The gala almost didn’t happen

As the nation’s capital filled with dignitaries and honored guests, Sinatra’s crew was rehearsing at the National Armory. But as the slate of inaugural events began, a fierce winter storm descended, paralyzing much of the city. Performers who had returned to their hotel to change for the gala found themselves stranded in snowed-in cars, while others, like Merman, performed in the plain clothes they’d rehearsed in.

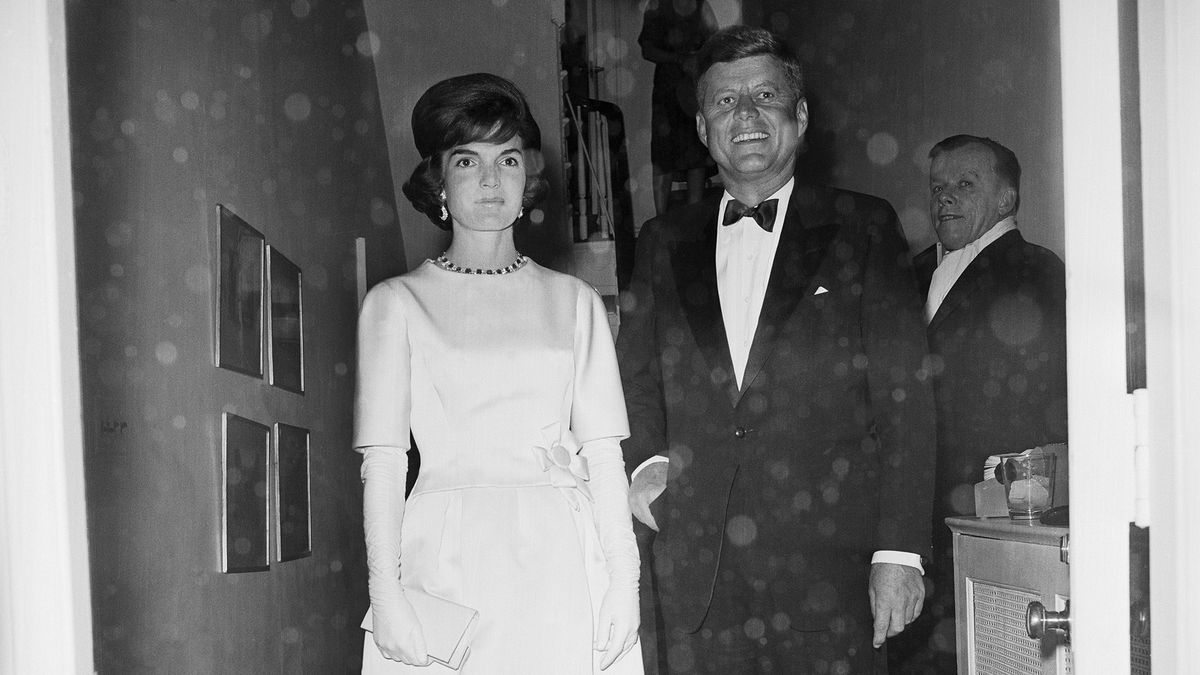

The January 19, 1961, gala eventually played to a smaller than expected crowd, with JFK, his wife Jackie and various Kennedy family members in attendance. Joseph had arranged for the gala to be filmed, but poor audio quality played havoc with his plans. Intented to be broadcast on television shortly after the inauguration, it was never shown, and was largely forgotten until it was edited and aired on public television stations in 2017.

READ MORE: Why Jacqueline Kennedy Didn’t Take Off Her Pink Suit After JFK Was Assassinated

JFK’s friendship with Sinatra eventually shattered

Sinatra had long been plagued by his rumored close ties to organized crime figures and may have been pressured by Joseph during the campaign to use those ties to secure the critical union vote for John. But after the election, the Kennedys began to distance themselves from Sinatra. In 1962, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover presented Attorney General Robert Kennedy with evidence that allegedly romantically linked both Sinatra and JFK with Judith Campbell, who was also involved with crime boss Sam Giancana.

Robert, famously anti-mob, sprang into action. He forced brother-in-law Lawford to cancel a long-planned stay by JFK at Sinatra’s Palm Springs home. Just as Davis had been a year earlier, Sinatra was devastated, angrily destroying the new additions he had built in expectation of the presidential visit. He never spoke to Lawford or JFK again.

Thank you for reading this post Inside the Long-Forgotten JFK Inaugural Gala at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: