You are viewing the article How Ulysses S. Grant Earned the Nickname ‘Unconditional Surrender Grant’ at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

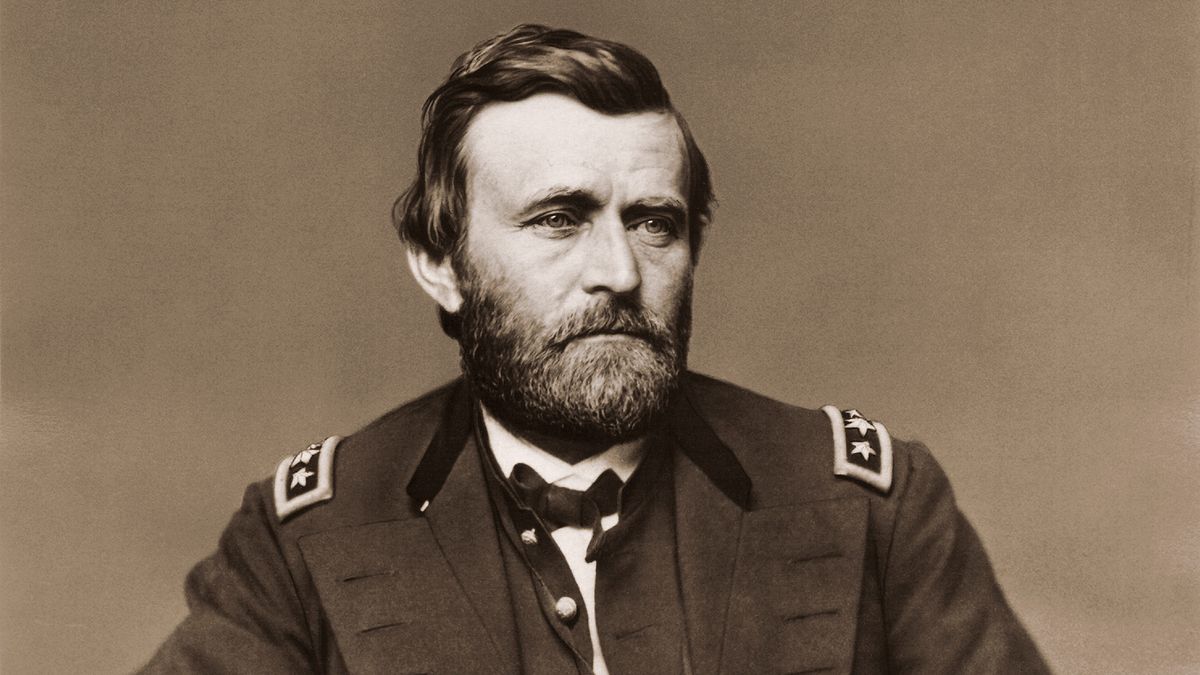

Ulysses S. Grant, the 18th President of the United States, was not only a renowned military strategist but also a man who earned a well-deserved nickname that would go down in history – ‘Unconditional Surrender Grant’. This moniker, bestowed upon Grant during the Civil War, epitomizes his relentless determination, unwavering commitment, and unmatched ability to secure victory by utterly crushing his enemies. Grant’s exceptional leadership skills and strategic brilliance are mirrored in his tireless pursuit of unconditional surrenders from Confederate forces, ultimately proving instrumental in the Union’s triumph. In this essay, we will explore the pivotal events and military campaigns that led to Grant’s acquisition of this formidable nickname, shedding light on the extraordinary man behind one of the most recognizable epithets in American military history.

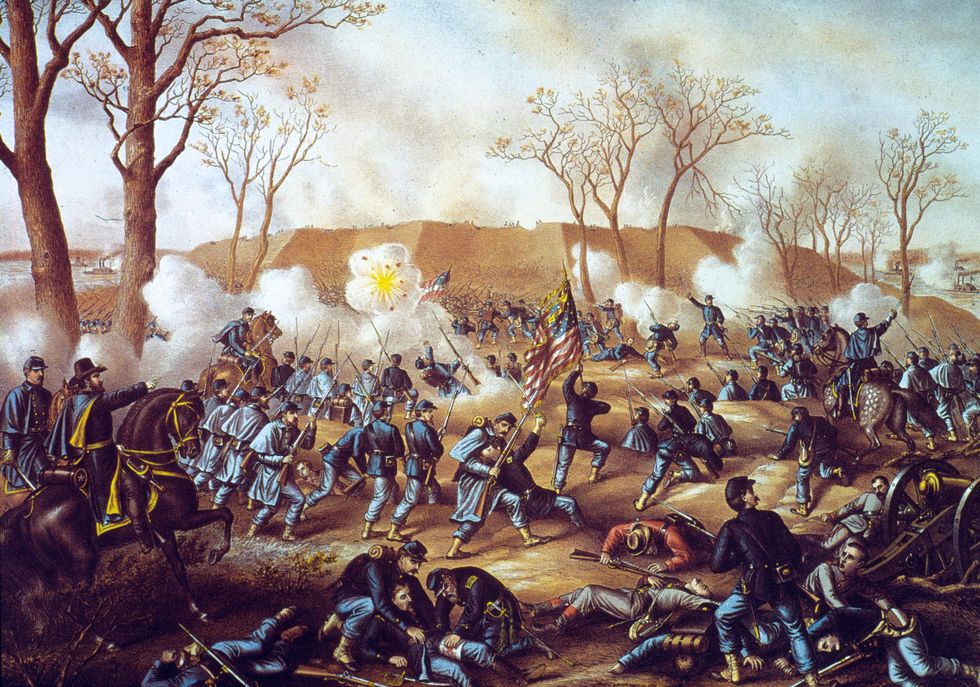

The capture of Fort Donelson, Tennessee, in February 1862 was the first major Union victory of the American Civil War, opening a path into the heart of the Confederacy. Fort Donelson also marked a turning point in the career of Ulysses S. Grant, whose steadfastness and resolve during the battle, including his refusal to accept anything less than a complete and total Confederate surrender, catapulted him to fame.

Much of Grant’s early life had been a failure

Hiram Ulysses Grant (he became known as Ulysses S. Grant because of a mistake on his West Point recommendation letter) graduated from West Point in 1843, an indifferent student ranked 21 out of 39 students. Despite early success in the Mexican-American War, Grant spent years in desolate Army outposts (where his loneliness led to the drinking that would mar his reputation). He suffered a series of financial failures when speculative business ventures floundered, and post-Army life proved no better, as Grant failed as a farmer and struggled to pay off debts as a partner in the family leather goods business in Galena, Illinois.

The Civil War came at just the right time for Grant

After the outbreak of war in April 1861, Grant eagerly joined, taking command of an Illinois volunteer regiment. His first success came later that year when he captured Paducah, Kentucky. He was promoted to brigadier general in July 1861 and in early 1862 began closing in on two Confederate strongholds in western Tennessee. On February 6, Fort Henry, situated on the Tennessee River, surrendered before a full-scale assault led by Grant and U.S. Naval officer Andrew Hull Foote was launched.

Grant then turned his attention to the larger Fort Donelson on the nearby Cumberland River, a key gateway in the Western Theater guarded by 16,000 Confederate troops. By February 13, Grant’s 25,000 men had surrounded the fort, with additional naval support. Fighting waged back and forth, with naval bombardment’s weakening the fort’s defenses, followed by a Confederate counter-assault that nearly broke Grant’s lines.

Victory came after the fort’s commander Brigadier General John B. Floyd withdrew his forces, rather than press Grant’s troops. Realizing their situation was hopeless, Floyd turned over his command to General Simon Bolivar Buckner, and he and other Confederate officers, including Nathan Bedford Forrest made their escape, leaving Buckner to coordinate a surrender with Grant.

Buckner had every reason to expect that Grant would agree to a negotiated surrender

Not only was it a standard military tradition of the time, but the two had known each other for decades. They attended West Point at the same time and had served together in the U.S. Army during the Mexican-American War. When Grant was struggling in his post-Army, pre-Civil War days, Buckner had once loaned him money during a particularly low period in Grant’s life.

To Buckner’s shock, Grant refused to negotiate. On February 16, he sent a legendary response:

Sir: Yours of this date proposing Armistice, and appointment of Commissioners, to settle terms of Capitulation is just received. No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.

However, when the two men finally met for the first of several days of meetings, Grant’s dictate of “unconditional surrender” softened considerably. While Buckner and his men became prisoners of war, Confederate soldiers were allowed to keep their personal belongings, and commissioned officers kept their guns and swords (an unusual allowance). Grant provided rations for Buckner’s desperately hungry troops and allowed wounded Confederates to be treated in Union hospitals in Kentucky. He even reportedly tried to repay Buckner for his long-ago loan, although Bruckner brusquely refused him.

Despite pressure from his own staff and officers, Grant did not insist on a formal surrender ceremony, wishing both to protect soldiers on both sides from the winter weather and not wanting to embarrass Buckner and his men, stating “We have the fort, the men, the guns. Why should we go through vain forms and mortify and injure the spirit of brave men, who, after all, are our own countrymen?”

Grant’s victory at Fort Donelson made him a legend

The North, desperate for a victory, immediately took to Grant. Newspapers heralded his success, nicknaming him “Unconditional Surrender” Grant. Accounts of Grant calmly smoking a cigar during his meetings with Buckner led to thousands of grateful Northerners sending them as gifts — with the unintended consequence of worsening the smoking addiction that led to his fatal throat cancer. Mark Twain was so taken with Grant that he reportedly carried his letter to Buckner with him for the rest of his life. The two later became close friends and Twain published Grant’s best-selling memoirs, which provided a desperately needed financial cushion for Grant’s family.

Most importantly, Fort Donelson put Grant on the radar of President Abraham Lincoln, who was also desperately in need of both victories and the capable, determined officers who could provide them. Grant was quickly promoted to major general of volunteers. When Grant faltered on the first day of the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, Lincoln was pressured to remove him from command. He refused, stating, “I can’t spare this man. He fights.” Grant proved Lincoln right the next day, eking out a bloody victory. It was a pattern that would repeat itself for the rest of the war, as the shocking body count of Grant’s victories earned him a new reputation, that of a “butcher.”

Grant would later capture two more Confederate armies

In July 1863, as the Battle of Gettysburg raged on in the East, Grant captured the key Confederate port at Vicksburg, Mississippi after a 47-day siege. His counterpart, Lieutenant General John Pemberton, surrendered on July 4, correctly hoping that he could extract sympathetic terms from Grant on America’s Independence Day. Although Grant captured 30,000 Confederate troops, he negotiated the parole of many of them, some of which returned to fight for the South. Vicksburg, however, gave the Union full control of the Mississippi River and cut the Confederacy in two.

And, most famously, after becoming head of the Union Army, Grant accepted the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, marking the end of major fighting in the Civil War. As at Fort Donelson, Grant proved a magnanimous victor, allowing Lee and his men to retain their weapons, horses and mules, and return home to their families, while again providing food for starving Southern troops. When Grant’s soldiers began an impromptu celebration as Lee rode away, Grant immediately stopped it, later recalling, “The Confederates were now our countrymen, and we did not want to exult over their downfall.”

Grant’s foes at Fort Donelson paid him the ultimate compliment

Following his two controversial, scandal-plagued terms as president, Grant retired to New York, where he died in July 1885, aged 63. Among his pallbearers were several Union generals who had fought closely by his side during the war, including William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Sheridan. Perhaps more surprising were two former Confederate generals who also served as honorary pallbearers, Joseph E. Johnston and Simon Bolivar Buckner, whose surrender to Grant 23 years earlier had marked a key turning point in the American Civil War.

In conclusion, Ulysses S. Grant earned the nickname ‘Unconditional Surrender Grant’ due to his relentless and unwavering determination to defeat the Confederate forces during the American Civil War. His military strategies and decisive actions demonstrated his commitment to achieving victory, often requiring the complete and unconditional surrender of enemy forces. Grant’s reputation as a strong and formidable leader grew with each successful campaign, solidifying his status as a key figure in American military history. Despite facing numerous setbacks and challenges, Grant’s unwavering resolve and relentless pursuit of victory earned him the respect and admiration of both his troops and the Union leadership. His relentless pursuit of the total surrender of the enemy’s forces ultimately led to the Union’s victory and played a significant role in the outcome of the Civil War. Ulysses S. Grant’s relentless determination and willingness to accept nothing less than total victory rightly earned him the nickname ‘Unconditional Surrender Grant’, a moniker that will forever be associated with his monumental achievements in the military realm.

Thank you for reading this post How Ulysses S. Grant Earned the Nickname ‘Unconditional Surrender Grant’ at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. What does the nickname ‘Unconditional Surrender Grant’ mean?

2. How did Ulysses S. Grant get his nickname?

3. What was Ulysses S. Grant’s strategy during the Civil War?

4. Which battles did Ulysses S. Grant win that led to his nickname?

5. How did Ulysses S. Grant approach surrender negotiations?

6. What were the reactions to Ulysses S. Grant’s unconditional surrender demands?

7. Did Ulysses S. Grant ever refuse to accept surrender terms?

8. How did Ulysses S. Grant’s unwillingness to compromise impact his military career?

9. How did Ulysses S. Grant’s nickname influence his reputation as a general?

10. Did Ulysses S. Grant’s nickname affect his later political career?