You are viewing the article How Sacha Baron Cohen Created the Character Borat at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

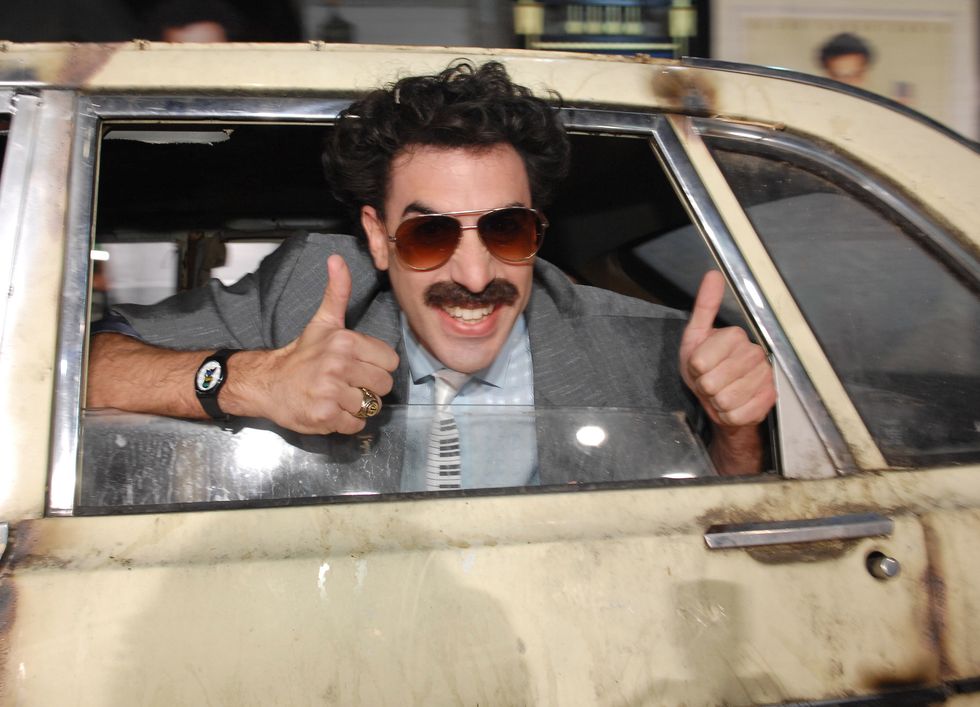

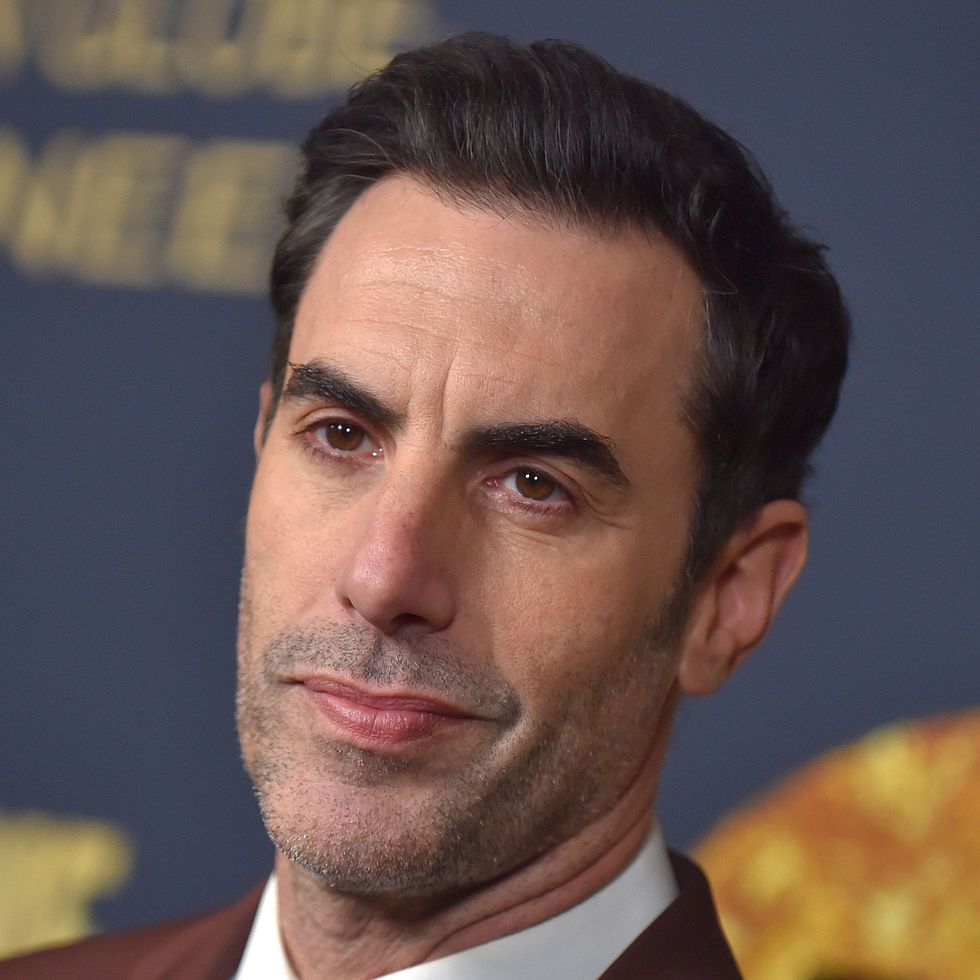

Sacha Baron Cohen is a name that resonates with comedy enthusiasts around the world. Known for his boundary-pushing and often controversial characters, one of his most iconic creations is the fictional Kazakh journalist, Borat Sagdiyev. With his thick accent, ludicrous behavior, and outrageous adventures, Borat became a cultural phenomenon and a subject of extensive debate. In this article, we will delve into the fascinating journey of how Sacha Baron Cohen brought this enigmatic character to life, exploring the origins, development, and impact of Borat on both comedy and society. From its humble beginnings to its meteoric rise, discover how Sacha Baron Cohen cleverly crafted Borat, leaving an indelible mark on the world of entertainment.

It started as an accident of sorts. Sacha Baron Cohen was hosting TalkTV on London Weekend Television and went out on the streets to pre-tape a few segments in character. He was dressed up as a hip-hop DJ who was “so keen to be presented as a gangsta,” when he spotted a group of “skateboarders who were also dressed like wanna-be gangstas.” So he started interacting with them as his alter egos.

As soon as he realized that the skateboarders never doubted his identity, Baron Cohen realized he had stumbled onto a newfound form of storytelling — documenting real people as they are by egging him on as exaggerated comedic characters. Before he knew it, his DJ persona had commandeered a tour bus, snuck into a secure office building and break-danced in a pub until the cops were called.

“We were walking over the Waterloo Bridge, back to the London Weekend Television studio, and the adrenaline was pumping and we were just so excited, because here was this new form of comedy that we discovered,” he told Rolling Stone in a rare 2006 story as himself. “Probably it existed, and other people had done it, but we’d never discovered it before – this idea of taking a comic character into a real situation.”

A Russian doctor inspired Borat

Baron Cohen soon perfected and patented his methodology, fine-tuning that first DJ into Ali G and also developing a fashion reporter who chased down celebrities called Bruno. He also started playing around with another personality, a foreign reporter named Alexi Krickler from Moldova, struggling to understand British culture in such silly ways to the point he didn’t understand why real lions weren’t on the rugby field during British Lions games.

Taking that faux journalistic skill on the road, he made a little observation about human nature that helped him propel his skills. “I was struck by the patience of some of these members of the upper class, who were so keen to appear polite — particularly on camera — that they would never walk away,” he told Rolling Stone.

Not long after that, he was on vacation in the southern Russian beach city of Astrakhan when he came across a doctor with an eccentric personality. “Within seconds, me and my friends were crying with laughter,” he remembered. “He had some elements of Borat, but he had none of the racism or the misogyny or the anti-Semitism. He was Jewish, actually.” Eventually, that chance meeting would plant the seeds of the “very nice” character of Borat Sagdiyev.

Baron Cohen was about to give up comedy when he got a late-night show audition

While his characters were brewing, his career wasn’t exactly finding that same traction. Baron Cohen had originally given himself five years from the time of his college graduation to succeed in the entertainment industry before he’d succumb to another field.

“I was sitting on a beach in Thailand. It was four years and 10 months since I’d graduated, and I had just come back from my brother’s wedding in Australia,” he recalled to Rolling Stone. “I was thinking about staying in Thailand, because I was having this very nice life on a pound-fifty a day. And that’s when I got a call from my agent saying there’s this audition for The 11 O’Clock Show, this satirical late-night show, and they were looking for a host. I remember telling her that I didn’t know if I wanted to come back. I had been rejected so many times that I didn’t know if it was worth it.”

Nevertheless, he went for it. But his audition didn’t quite charm the producers the way he had hoped. Instead, he showed footage of himself in character as Alexi Krickler at a pro-fox-hunting rally — and he immediately landed the job.

He had to film the first Borat movie in places where fewer people would recognize him

It was Baron Cohen’s unique skill set of uncovering human stories through his exaggerated character that quickly helped him win over an audience at The 11 O’Clock Show. His Ali G segments were so popular that it became its own series, Da Ali G Show. While that brought British fame, it was his appearance in Madonna’s music video for “Music” that also made him a familiar face in the U.S. — and soon his show, which featured all three characters, aired in America on HBO.

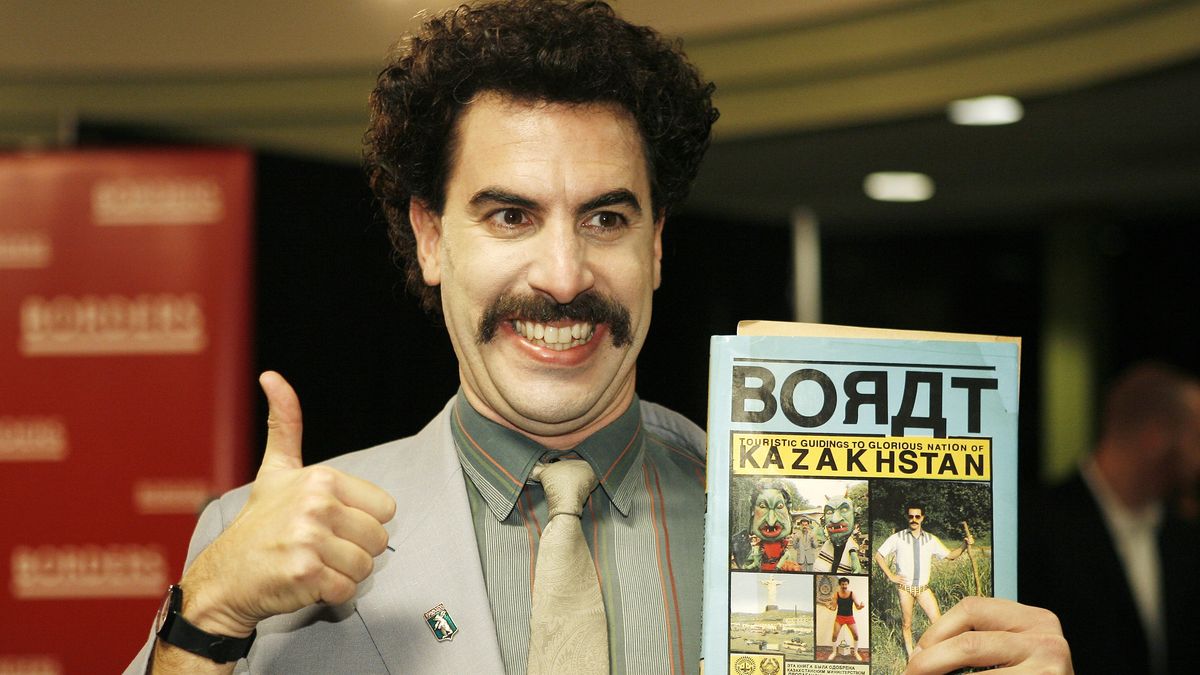

By this time, Krickler had faded away and Borat had taken over as the reporter persona, transforming into a Kazakh journalist. “The reason we chose Kazakhstan was because it was a country that no one had heard anything about, so we could essentially play on stereotypes they might have about this ex-Soviet backwater,” he explained to Rolling Stone. “The joke is not on Kazakhstan. I think the joke is on people who can believe that the Kazakhstan that I describe can exist — who believe that there’s a country where homosexuals wear blue hats and the women live in cages and they drink fermented horse urine and the age of consent has been raised to nine years old.”

The inherent problem with his characters was that the more popular they became, the less he could go undercover in costume. When Borat became ready for the spotlight in his 2006 movie Borat!: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, all the filming had to happen where audiences had less access to cable networks, which ended up being in the Deep South.

What makes Baron Cohen so successful is that he never breaks character. He starts by warming his subject up with a Kazakh cigarette or by presenting them with a gift, be it a cookie bag or overzealous kiss, but in reality that’s simply Borat’s puppetmaster Baron Cohen feeling out how to interact with this particular subject in a way that would work best on film. As proof of his commitment, even when the Secret Service stopped the crew near the White House, Baron Cohen never showed any signs of his real British persona.

The second movie was filmed before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Fifteen years after filming the movie, Baron Cohen decided to go for a sequel — an exponentially more difficult task now that Borat himself was pretty much a global celebrity. Yet that little hiccup only propelled him to be more creative, and thoughtful about the changing times, as the sequel Borat Subsequent Movie Film: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan was filmed both pre- and mid-pandemic and released ahead of the November 2020 election.

By changing up costumes (like dressing up as Donald Trump to crash a Mike Pence speech) and bringing in a daughter for Borat, Baron Cohen was able to keep up his antics in front of boldface names, like Rudy Giuliani. For other scenes, audiences were surveyed ahead of time to see if they recognized Baron Cohen before being invited to interact, Vanity Fair explained. He even managed to infiltrate the lives of Southern folks in Mississippi. “I lived in character for five days in this lockdown house,” he told the paper. “I was waking up, having breakfast, lunch, dinner, going to sleep as Borat when I lived in a house with these two conspiracy theorists. You can’t have a moment out of character.”

It’s exactly those moments that have made Baron Cohen’s talents so clear, even as so many of the film’s moments appeared in the real news with the advent of social media.

And as the ultimate proof of just how real a fake personality in a mockumentary can be, Baron Cohen says that Pamela Anderson wrote on her divorce papers that the reason for her divorce from Kid Rock was “Borat.” “I thought it was a joke, but it was actually true,” Baron Cohen told the Times.

In conclusion, Sacha Baron Cohen’s creation of the character Borat can be described as groundbreaking and audacious. Through his brilliant portrayal, Cohen managed to expose societal prejudices, highlight cultural stereotypes, and challenge the biases that exist within our communities. Borat’s irreverent and controversial approach made him a cultural icon, sparking important discussions about racism, misogyny, and xenophobia. Cohen’s ability to blur the lines between reality and fiction added to the character’s authenticity and impact, leaving audiences both entertained and introspective. Whether one views Borat as a satire, a social experiment, or simply a comedy character, there is no denying the power and influence he has had on popular culture. Sacha Baron Cohen’s innovation and fearlessness have forever changed the landscape of comedy and will continue to be studied and appreciated for years to come.

Thank you for reading this post How Sacha Baron Cohen Created the Character Borat at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. “Sacha Baron Cohen’s inspiration for Borat character”

2. “Borat character development process”

3. “Sacha Baron Cohen’s research for Borat character”

4. “Borat’s impact on pop culture”

5. “Behind the scenes of Borat’s creation”

6. “Interviews with Sacha Baron Cohen about Borat”

7. “Borat’s influence on political satire”

8. “Sacha Baron Cohen’s transformation into Borat”

9. “The controversy surrounding Borat’s character”

10. “Sacha Baron Cohen’s comedic approach to Borat’s humor”