You are viewing the article How Mozart Made — and Nearly Lost — a Fortune at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was one of the most successful musicians of his era, but the popular play and film Amadeus portrays this classical genius dying penniless, cast off in an unmarked grave as the victim of murder at the hands of his rival fellow composer Antonio Salieri. In reality, Mozart made a fortune during his brief lifetime but seemed determined to spend every cent of it, leading to lifelong money woes — and centuries of misconceptions about his final years.

Mozart spent much of his career as a freelancer

A musical prodigy who composed his first works while still a child, Mozart spent his early years touring much of Europe. By his early teens, he had settled into a position with the Archbishop of Salzburg, where he supplemented his modest salary with outside commissions, sometimes being paid in jewelry and trinkets instead of cash. But his growing ambition and ego put him at odds with the Archbishop, and by his early 20s, he’d left the position and moved to Vienna.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Mozart proved unwilling (or unable) to take on a full-time position at court. Instead, he cobbled together whatever work he could find. He gave music lessons to the children of the rich, conducted and performed his own works as well as those of others (in one six-week stretch in 1784 he gave a remarkable 22 concerts), and took on every commission offered for new works. He traveled frequently, greatly enhancing his reputation, but sometimes at a financial loss, as he often had to pay for his travel costs.

But the ups-and-downs of life as a musical journeyman paid off, according to a 2006 exhibit marking the 250 anniversary of his birth. Records show that by the 1780s, Mozart was earning as much as 10,000 florins a year, and a letter from Mozart’s father stated that he had been paid 1,000 florins for just one (presumably memorable) concert performance. At a time when laborers took home 25 florins annually and many in the upper class cleared 500 florins, Mozart’s salary would have placed him the upper echelon of Vienna’s rich.

He and his wife lived an extravagant lifestyle

In August 1782, despite his father’s misgivings, Mozart married Constanze Weber, whose elder sister Mozart had unsuccessfully courted. Weber hailed from a musical family herself, and she and her sisters had made names for themselves as singers. The couple were devoted to each other, and had six children, though only two survived infancy.

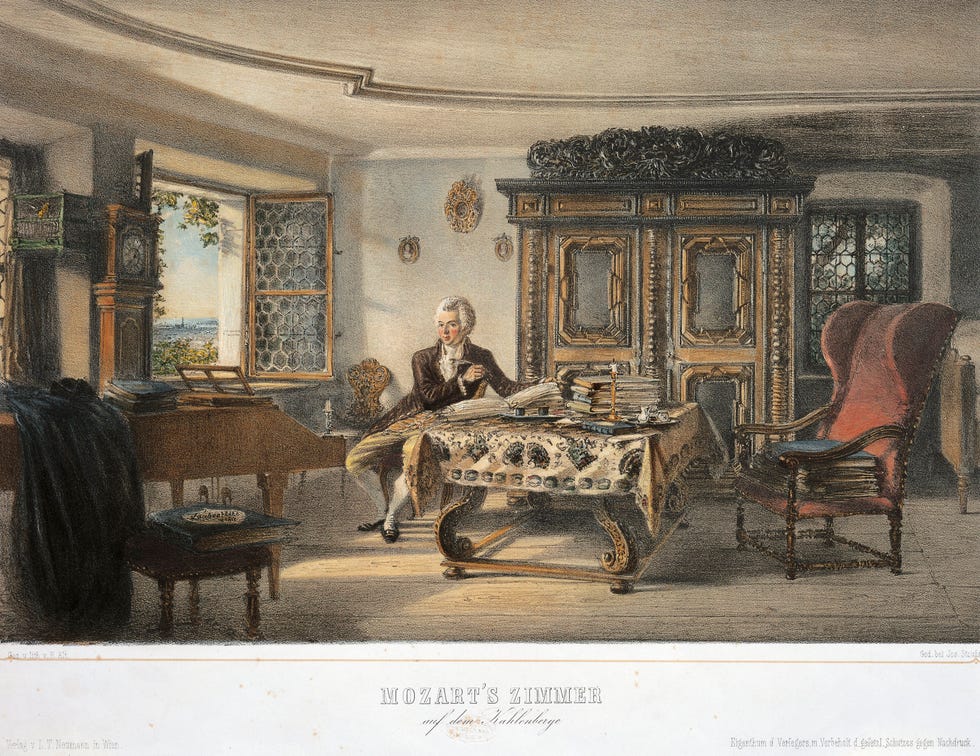

The Mozarts had a large, roomy apartment in a chic area of Vienna, located just behind St. Stephen’s Cathedral. Despite the ups and downs of Mozart’s finances, they were determined to maintain a high standard of living, in large part because Mozart moved in aristocratic circles. They sent their son to an expensive private school and entertained lavishly. But the couple frequently spent far beyond their means, and debts to retailers and creditors piled up.

The family was forced to move several times, and some historians believe Mozart may have squandered large sums of money at the gambling table, although others believe betting was just a pastime, not a compulsion. More recently, some have theorized that Mozart’s chronic overspending (as well as his frequent and extreme mood changes) were symptoms of an undiagnosed mental illness, possibly manic depression or bipolar disorder.

Mozart’s financial security took a hit due to circumstances beyond his control

Around 1788, his wife suffered a series of medical crises that proved nearly fatal. Her recovery included extended visits to expensive spas, further draining his coffers. Mozart embarked on a series of shorter tours to raise funds, but they ended in financial failure.

Changes in musical taste, as well as Austria’s expensive involvement in a series of on-going wars, caused a downturn in commissions, as Mozart briefly fell out of favor and wealthy clients turned their attention elsewhere. The result was a dark period of depression, which Mozart frequently mentioned in letters to friends. While the Mozarts were never in danger of going hungry, they seemed unwilling to lower their overhead, leading Mozart to beg friends and patrons for loans during these lean years. However, these were promptly repaid whenever a new commission came in.

Mozart was not buried in a pauper’s grave

In fact, his financial prospects were on the upswing. Although she has been maligned as flighty, childish and naïve, Constanze played a key role in this financial resurgence. While Mozart had kept the worst of their financial troubles from her during her illness, once recovered, she went into action. The couple moved from the center of Vienna to a cheaper suburb (although they continued to spend heavily), and she helped organize his chaotic business affairs.

New business opportunities, including stipends from several smaller European courts and a lucrative offer to compose and perform in England, promised possible financial relief. Mozart produced a flurry of remarkable work in his final years, including the opera “Die Zauberflöte” (The Magic Flute), which premiered just months before his death and was an immediate success.

But Mozart’s health began to fail in the fall of 1791, and he died, aged just 35 in December. His death was likely caused by kidney failure and a recurrence of the rheumatic fever he had battled on and off throughout his life. Austrian customs of the time precluded anyone other than the aristocracy from having a private burial, so Mozart was laid to rest in a common grave with several other bodies — not a pauper’s grave. Several years later, his bones were dug up and reinterred (also the practice of the time), and his exact final burial spot remains a mystery.

Constanze, just 29 and with two young children, was devastated by his death. After paying off the last of his debts, she found herself with little left. Once again, her industriousness paid off. She arranged for the publication of several of her husband’s works, organized a series of memorial concerts in his honor, secured a small lifetime pension for her family from the Austrian emperor, and helped publish an early biography of Mozart, written by her second husband. These efforts not only left her financially secure for the rest of her life but also helped secure Mozart’s legacy as one of history’s greatest composers.

Thank you for reading this post How Mozart Made — and Nearly Lost — a Fortune at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: