You are viewing the article How George Washington Kept Alexander Hamilton in Check at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

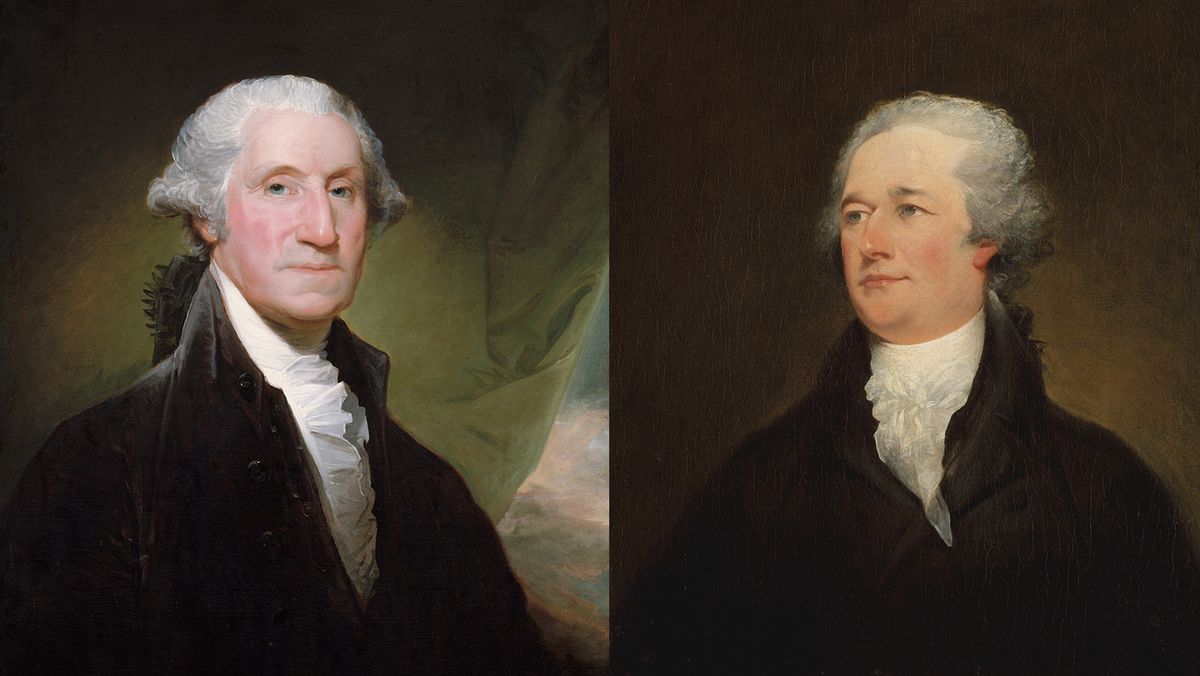

As Founding Fathers, George Washington and Alexander Hamilton were seemingly far more different than they were alike.

A member of the Virginia gentry, Washington was measured and stoic in public, patient to wait for his opportunities and secure enough in his abilities to solicit input from others.

Hamilton was passionate and impulsive, quick to voice his opinion and seemingly carrying a permanent chip on his shoulder from his origins as a child born to unwed parents in the West Indies.

Yet the two often saw eye-to-eye when it came to defending a country charting a treacherous path for independence, their complementary strengths proving a formidable force that blazed a path for crucial military and political successes.

READ MORE: A Timeline of George Washington’s Life

Washington recognized Hamilton’s intellect and abilities as a young officer

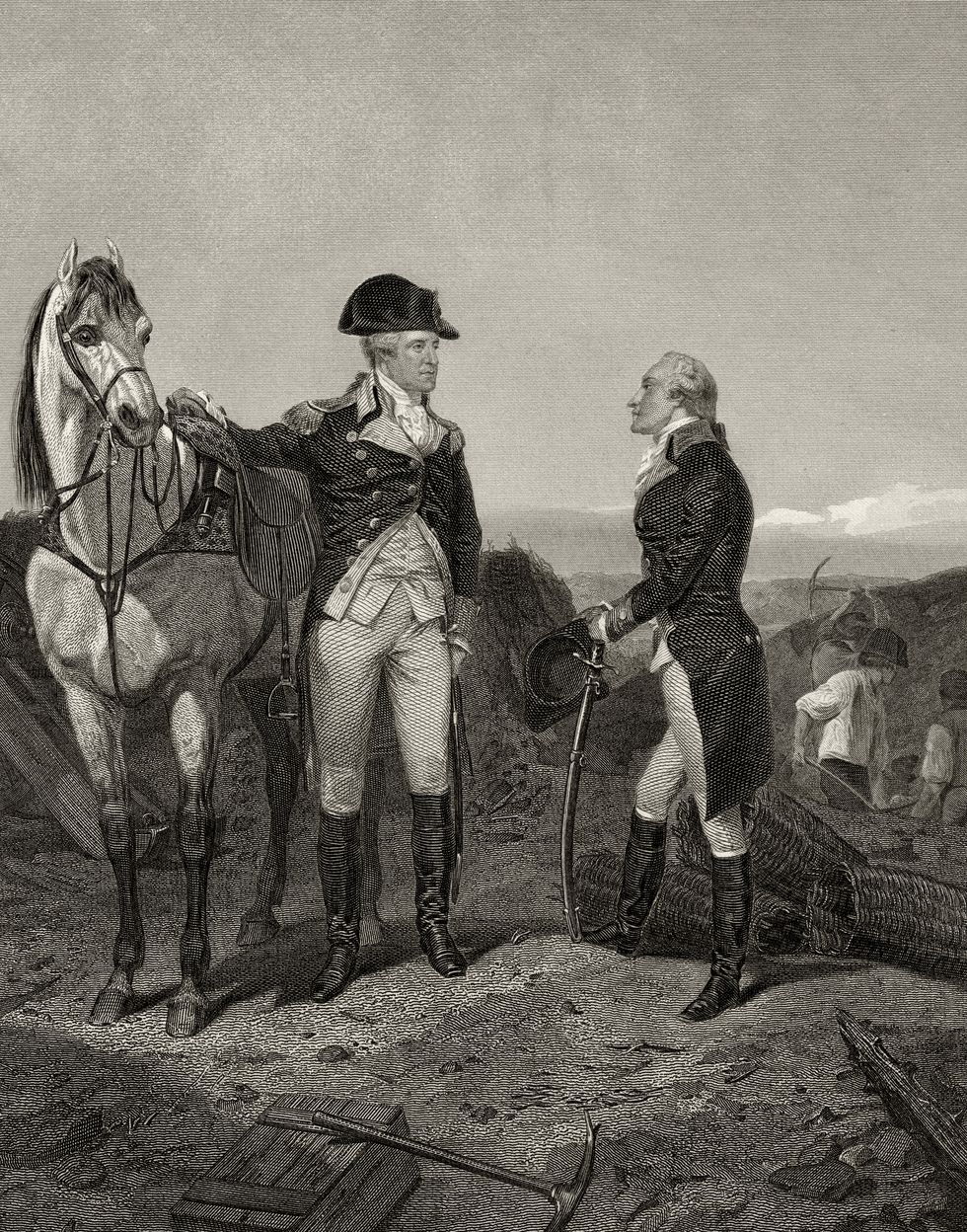

According to Ron Chernow’s Washington: A Life, Hamilton first came to General Washington’s attention early in the American Revolution, the young artillery captain standing out for his bravery during the disastrous 1776 New York Campaign that left the rebels retreating to New Jersey with their tails between their legs.

In early 1777, after Hamilton again showed his mettle during the tide-turning Battles of Trenton and Princeton, Washington asked Hamilton to join his personal staff as an aide-de-camp. Eager to earn accolades on the battlefield, Hamilton had previously rejected such offers from other commanding officers, though there would be no turning down the leader of the Continental Army.

Thus marked the start of a complex relationship. As Chernow noted, Hamilton admired his boss as a man of tremendous courage and integrity, but considered him a general of only “average” ability and found him to be “snappish” and “difficult.” And Washington never mustered the personal affection toward him that he had for other officers young enough to be his son, like the Marquis de Lafayette.

But Washington also saw in him the ambition for continual self-improvement that had fueled his own rise and a disposition for honest dealings. Furthermore, Hamilton’s impressive intellect and powers of persuasion made him indispensable as both a military strategist and a proxy voice when carrying out the general’s orders elsewhere.

That indispensability led to the greatest source of friction between the two, as Washington refused to cut Hamilton loose to achieve the battlefield glory he craved. Things came to a head in February 1781, when Washington scolded his aide for keeping him waiting for a meeting. Hamilton abruptly quit and vented his frustrations in a letter to his father-in-law, writing, “For three years past, I have felt no friendship for him and have professed none.”

Hamilton soon returned to Washington’s orbit, his ego soothed by the elder’s entreaties to mend relations. Later that year, the general gave in and appointed Hamilton a field commander for the decisive Battle of Yorktown.

Hamilton became the most valued member of Washington’s cabinet

Washington and Hamilton went their separate ways after the Revolution until the factions pulling the nascent country in different directions pushed both back into the political fray. After Washington was unanimously elected the first U.S. president in 1789, he made Hamilton his first cabinet selection as secretary of the Treasury.

Washington soon realized he had his hands full with the clashing viewpoints of Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, the secretary of state. To Jefferson’s chagrin, the president sided with Hamilton’s proposals for a national bank and the federal assumption of state debts. Washington also seemingly trusted the Treasury secretary more on matters of foreign relations, such as the call for neutrality as tensions rose between the British and French, leading to Jefferson’s resignation at the end of 1793.

Hamilton further endeared himself to Washington with his support of mobilizing troops against the insurgents of the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794, his presence a stark contrast to that of the missing secretary of war, Henry Knox, who was tending to business interests in Maine.

Even after Hamilton left the cabinet in early 1795, Washington continued to seek his counsel with an explanation of the finer details of the Jay Treaty with Great Britain. And when Washington reached the end of his line with partisan politics, he had Hamilton compose his farewell address in 1796, his longtime aide smoothing over the exhausted president’s petty gripes to deliver the resolute words the public had come to expect from their hero.

READ MORE: 10 Quotes From George Washington

Hamilton’s life unraveled after Washington’s death

His trusted advisor still on his mind, Washington reached out after news of Hamilton’s extra-marital affair became public in 1797, sending a wine cooler and a thoughtful note that expressed his support without mentioning the infraction.

The following year, with the country teetering on the brink of war with France, Washington accepted President John Adams’ appointment as senior commander of the U.S. Army on the grounds that Hamilton becomes his deputy. “By some he is considered as an ambitious man, and therefore a dangerous one,” Washington wrote to his successor. “That he is ambitious I shall readily grant, but it is of that laudable kind, which prompts a man to excel in whatever he takes in hand.”

Their fruitful partnership came to an end with Washington’s death on December 14, 1799. Shortly afterward, Hamilton wrote, “I have been much indebted to the kindness of the General, and he was an Aegis very essential to me.”

Indeed, Hamilton’s life began to unravel without Washington around to provide political protection and rein in his impulses. Hamilton supported his old enemy, Jefferson, over Aaron Burr in the 1800 presidential election, damaging his standing at the head of the Federalist Party. And when Hamilton continued to badmouth Burr during the 1804 New York gubernatorial election, Burr silenced him for good with a bullet in their fateful duel that July.

As Chernow and other historians have pointed out, Washington and Hamilton never became great friends despite all the time spent working in close proximity – their built-in differences too strong to entirely surmount the personal buffers. Still, it was clear that the two brought about the best in one other when it came time for action, their partnership providing so much of the foundation for the republic that endured from its tenuous beginnings.

Thank you for reading this post How George Washington Kept Alexander Hamilton in Check at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: