You are viewing the article How Dick Cheney Went From Yale Dropout to Vice President at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Today Dick Cheney is known as George W. Bush’s vice president and a GOP stalwart. But before taking on Washington, Cheney’s road was less than perfectly paved with many bumps that had an influence on his political outlook and rise to the top. Here’s a look at how a young Cheney found his path in life and politics.

Cheney failed out of Yale twice

Upon graduating high school, Cheney was accepted to Yale and offered a full-ride scholarship. However, due to poor grades, he failed out twice. While his college career was derailed, Cheney returned to school — after working as a lineman — and received a bachelor’s and master’s in political science from the University of Wyoming. Wanting to become a professor, in 1966 he headed to the University of Wisconsin to pursue a PhD (along with his wife, Lynne).

Cheney successfully interned for Wisconsin Governor Warren Knowles, then was asked to run a congressional campaign in Wisconsin in 1968. However, his school didn’t like the idea of Cheney postponing August preliminary exams for his doctorate to take the job. Still thinking of an academic career, he turned down the campaign. Yet his professors didn’t frown upon him taking a congressional fellowship that started in September 1968. Cheney, therefore, began working in Washington, D.C. — an opportunity he would have had difficulty accepting if he’d been in the middle of that congressional campaign.

He almost worked for Ted Kennedy

Cheney’s year-long congressional fellowship called for him to work with both Republicans and Democrats. His first job was in the office of Representative William Steiger, a Republican from Wisconsin. Cheney then had an assignment waiting on the other side of the political aisle: working as deputy press secretary for Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy.

Cheney was born into a family of New Deal Democrats (his father was proud his son shared a birthday, January 30, with FDR), but he’d worked with Republicans in the Wyoming legislature and in Wisconsin. And he didn’t want to leave Steiger’s office, where he’d been given a great deal of responsibility. Fortunately for Cheney, there was another fellow who was happy in the “Lion of the Senate’s” office, so the two finagled their paperwork without changing jobs.

Donald Rumsfeld didn’t initially like Cheney

Another person Cheney encountered while on his fellowship was Donald Rumsfeld, then a congressman from Illinois. Rumsfeld didn’t warm to Cheney at first but was won over after reading a memo Cheney had penned to help Rumsfeld through confirmation hearings for a post in the Nixon administration. Rumsfeld ended up bringing Cheney with him to the Office of Economic Opportunity and the Cost of Living Council; Cheney became director of operations for the CLC.

When Richard Nixon decided to set price controls in 1971, in response to public worries about rising costs and inflation, Cheney helped create regulations for running the economy and supervised 3,000 IRS agents charged with enforcement. Being part of a government effort to control a multitude of economic components, from wages to the cost of bread, cemented Cheney’s devotion to the free market and limited government.

Cheney could have been involved in Watergate

After he began working in the Nixon White House, Cheney had helped coordinate a surrogate speaker program linked to Nixon’s re-election campaign. This led to Cheney being invited to join the Committee to Re-Elect the President, which was gearing up for the 1972 presidential race. Yet Cheney opted not to work on the campaign, sticking to his policy-oriented jobs instead.

Nixon won a second term in the White House in a landslide. But soon afterward the Watergate scandal broke — with the re-election committee in a starring role. Cheney saw people he would’ve worked with get caught up in the scandal’s fallout, with some heading to prison. As he noted in his memoir, being part of that committee “would be an albatross on anyone’s résumé.”

Two DUIs almost prevented him from becoming chief of staff

Cheney was working at an investment advisory firm when Nixon resigned due to the Watergate scandal and Vice President Gerald Ford became President in August 1974. Ford asked Rumsfeld to oversee the transition, and Cheney agreed to join Rumsfeld in serving the new president.

The assignment became permanent for Rumsfeld, who was tapped to be Ford’s chief of staff. Cheney was on track for a job as deputy staff coordinator under Rumsfeld, but his disclosure of two DUIs (received when he was working as a lineman after dropping out of Yale) as part of a clearance check with the FBI raised red flags. Cheney was almost out of a job until Rumsfeld went to bat for him. Thanks to this support, Cheney remained at the White House, where he stepped into the chief of staff job after Rumsfeld left. This made Cheney, at 34, the youngest person to ever hold the position.

He suffered a heart attack during his congressional campaign

Following Ford’s loss of the presidency to Jimmy Carter in 1976, Cheney moved back to Wyoming. He soon launched his own campaign to represent his home state in the House of Representatives. Then, during the primary, a 37-year-old Cheney suffered a heart attack.

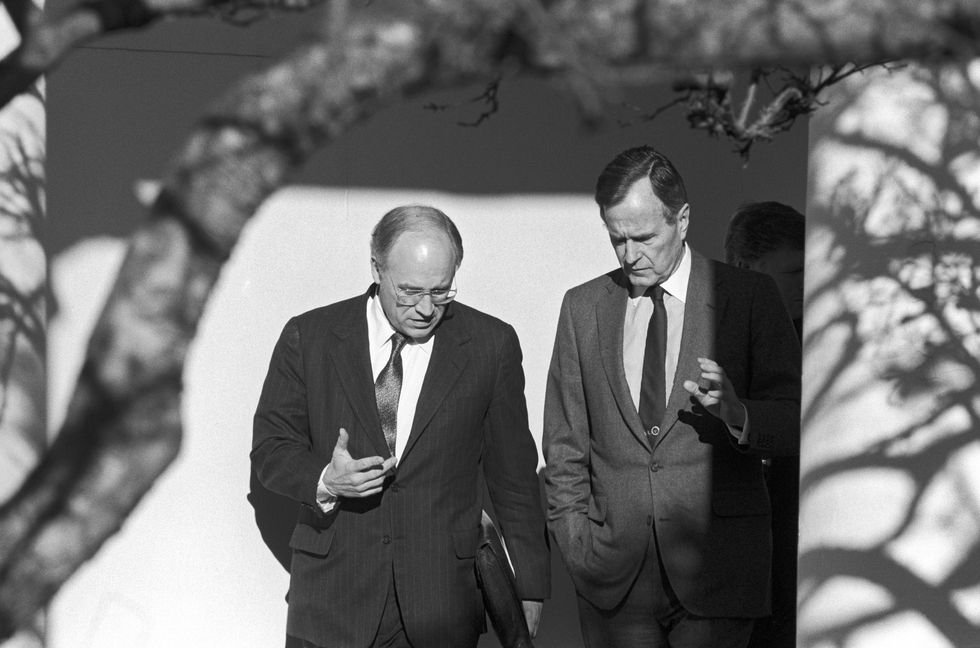

Conventional wisdom would suggest that continuing a grueling political race while recovering from a heart attack wasn’t the wisest course of action. But Cheney was disinclined to quit — and his doctor encouraged him to stick with a career he enjoyed. So Cheney wrote a letter to every registered Republican saying he would quit smoking (he’d been inhaling about three packs a day) and was staying in the race. He won the primary and was subsequently elected to Wyoming’s only House seat. The return to Washington, D.C. allowed his political rise to continue: Cheney would join Republican leadership in the House, become secretary of defense under George H.W. Bush, and eventually serve as vice president.

Thank you for reading this post How Dick Cheney Went From Yale Dropout to Vice President at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: