You are viewing the article How Carter G. Woodson’s Life’s Work Fueled the Creation of Black History Month at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

For the last four and a half decades, every February has marked the celebration of Black History Month — an annual observance that recognizes the achievements and contributions of Black Americans. But without historian Carter G. Woodson, who devoted much of his life to shining a light on Black history, the celebration might not exist. A century ago, the idea of highlighting Black accomplishments was all but nonexistent, and it is because of Woodson’s creation of Negro History Week in 1926 that Black History Month has become one of the most significant periods of the year.

Woodson went from impoverished beginnings to Harvard graduate

Woodson’s story began in a similar fashion to the countless number of Black people who came of age during the uneasy years of Reconstruction. The son of illiterate formerly enslaved people, he grew up on a farm near New Canton, Virginia, where intensive fieldwork kept him out of school most days and still barely produced enough food to feed the entire family.

Woodson took on the jobs that were available to him, including garbage truck driver and coal miner, but he also sought to improve his standing through a relentless desire to learn. Nearly 20 by the time he entered high school, he graduated in two years and later became the school’s principal as he worked toward his undergraduate degree at Kentucky’s Berea College.

After spending more than three years in the Philippines as a school supervisor, Woodson returned to the United States to earn a master’s degree at the University of Chicago in 1908. Four years later, he became the second Black man to earn a PhD in history from Harvard University, after W.E.B. Du Bois.

As noted in Carter G. Woodson in Washington, D.C., The Father of Black History, Woodson’s determination to shine a light on his predecessors’ stories solidified during his years on the supposedly progressive Harvard campus. He later recalled the moment when a distinguished professor informed his class that the “Negro had no history,” fueling the deep-seated desire to prove him wrong.

He founded Negro History Week in 1926

A few months after the spring 1915 publication of his first book, The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861, Woodson took a big step toward what would become his life’s work by co-founding the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH). The following year, he launched the Journal of Negro History.

Still involved in educational administration by that point — he became principal of Armstrong Manual Training School in 1918 and a dean at Howard University the following year — Woodson attempted to sell journal subscriptions and compile historical documents in what little free time he had. By 1922, he quit academia to devote his efforts to the ASNLH and its related enterprises, which operated out of his house in northwest Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, he urged Black schools and organizations to find ways to celebrate the accomplishments of their race. His Omega Psi Phi fraternity brothers responded with the creation of Negro History and Literature Week in 1924, and Woodson soon took the idea to the next level with a pamphlet that heralded the advent of “Negro History Week” in February 1926, to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln (February 12) and Frederick Douglass (February 14).

Woodson offered resources and guidance to promote his idea

Woodson claimed to notice a “stir in the direction of active participation” after mailing his first Negro History Week circulars to schools, civic organizations, literary societies and radio stations. He offered promotional materials to those who agreed to take up the celebration, as well as guidance on how to shape such festivities.

“We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in history,” he wrote in the 1927 Negro History Week circular. “What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hate, and religious prejudice. There should be no indulgence in undue eulogy of the Negro. The case of the Negro is well taken care of when it is shown how he has influenced the development of civilization.”

Early Negro History Week celebrations included banquets, speeches, parades and lectures, many of which were free for the public to attend. It caught on with the help of the teachers and church leaders who encouraged involvement, as well as the organizers and featured participants who were expected to generously donate their time to the cause.

Several Black newspapers also got on board with the idea, with the Philadelphia Tribune, the Chicago Defender and the Tampa Bulletin among the early supporters of the effort. By 1937, Woodson had another means of promoting Negro History Week with the launch of the Negro History Bulletin, a publication that proved more accessible to working-class Blacks and children than the scholarly Journal of Negro History.

He hoped to turn Negro History Week into a year-round focus on Black studies

Negro History Week became a mainstay in areas with major Black populations like New York City, Chicago, Detroit and Washington D.C., with Woodson publishing the enthusiastic feedback of teachers in the Negro History Bulletin, but he was already worried about the dishonest people seeking to make a profit off his hard work.

Writing in the Norfolk Journal and Guide in 1936, he criticized those who were “doing much to discredit the effort” by “using the opportunity as a racket to sell the public the spectacular for whatever cash may be obtained therefrom.”

Woodson also wasn’t satisfied with the celebration being limited to seven days out of the year. He hoped that Negro History Week would spark the development of immersive curricula on Black studies in schools around the country, but was disappointed by the failure of educators to build on his efforts.

“It is evident from the numerous calls for orators during Negro History Week that schools and their administrators do not take the study of the Negro seriously enough to use Negro History Week as a short period for demonstrating what the students have learned in their study of the Negro during the whole school year,” he wrote for the Negro History Bulletin, shortly before his death from a heart attack on March 3, 1950.

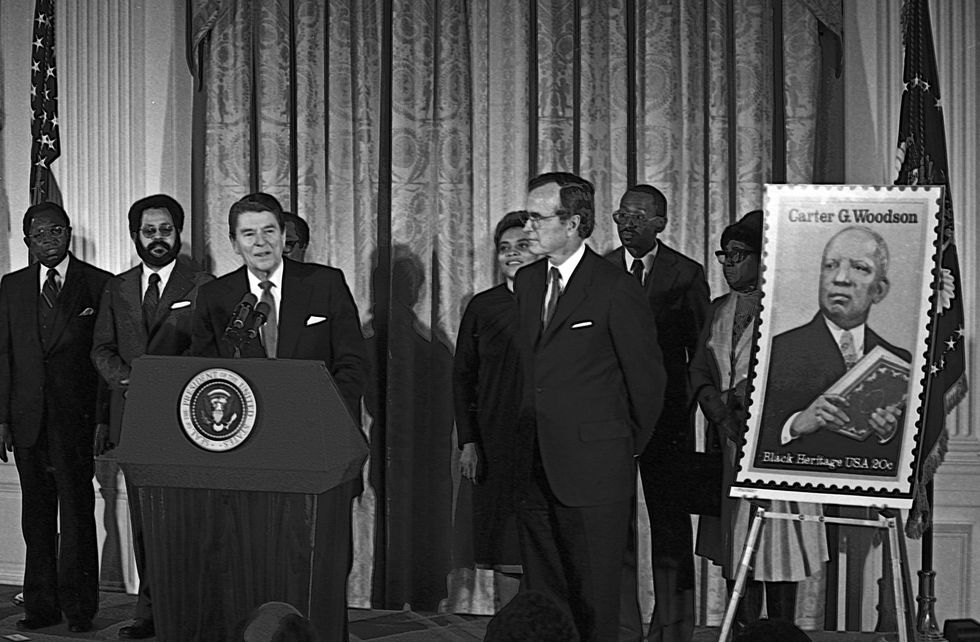

Black History Month was established in February 1976

While Woodson continuously found himself pushing upstream in pursuit of his goals, it’s apparent that his work with the ASNLH — now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) – bore fruit through successive generations that made Black studies a staple of most American institutes of higher learning.

Furthermore, momentum for Negro History Week continued gathering steam in the following decades, the commemoration of Black contributions becoming a cultural fixture following its expansion to Black History Month in February 1976.

All in all, it’s an impressive record for a son of formerly enslaved people, who not only won the argument about whether Blacks have a history, but also revealed a clear appetite for the subject among everyday people of all races.

Thank you for reading this post How Carter G. Woodson’s Life’s Work Fueled the Creation of Black History Month at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: