You are viewing the article How Alan Alda’s Real-Life Military Service Influenced ‘M*A*S*H’ at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

M*A*S*H, which began as a TV adaptation of an Oscar-winning anti-war movie, functioned first as a lighthearted sitcom set in the middle of a war zone. Over the years, as the show gained more acclaim and new creative forces accrued power in the writers’ room, M*A*S*H retained its comedic edge but increasingly went back to engaging with the more difficult and solemn issues connected to the United States’ wars in East Asia, taking what was widely recognized as an anti-war stance.

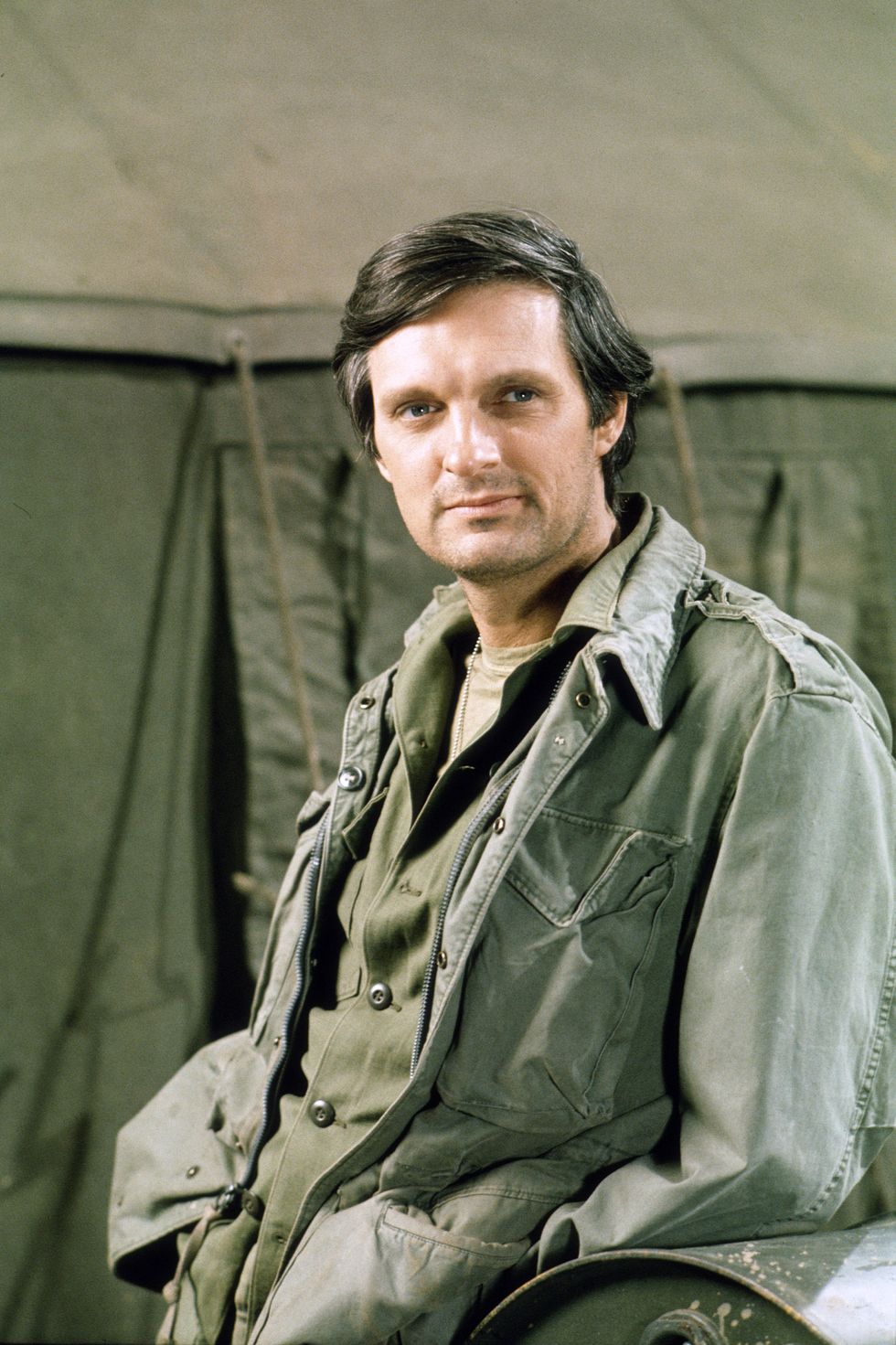

Much of that transition was driven by the show’s star, Alan Alda, who spent time himself serving in the military before playing heroic surgeon Hawkeye Pierce. Alda was one of many cast members and creative contributors to the Emmy-winning series to have fought — or at least spent time enlisted — in the military.

READ MORE: TV Stars Who Ruled the ’70s

Many of the show’s leaders were veterans

Like the movie, M*A*S*H was set during the Korean War, which by that point had ended nearly two decades prior, though American troops remained stationed in South Korea for decades after that. The United States’ busy mid-century of warfare meant that cast members and producers had a variety of experiences in the armed forces.

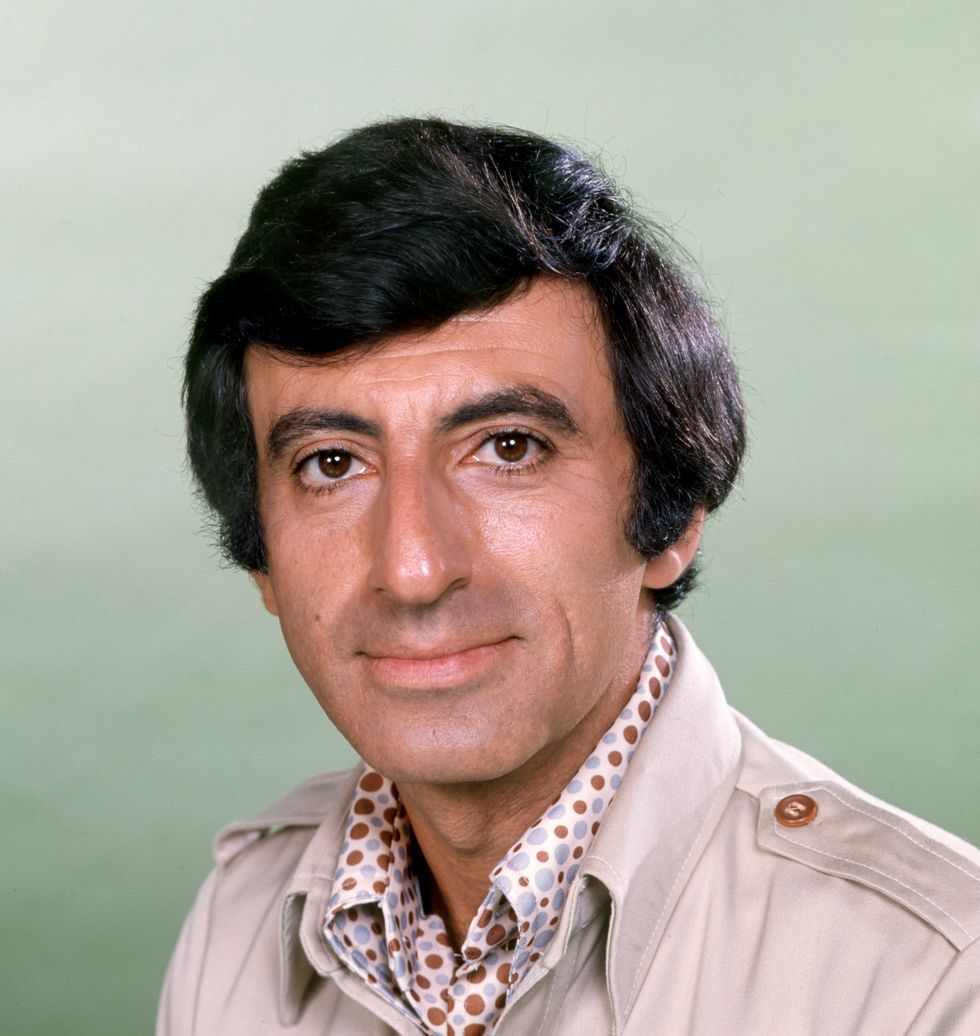

Two of the three male actors to last the entire series served stints in uniform. Alda enlisted in the Army Reserves after college and spent six months stationed in Korea. Costar Jamie Farr, who played Maxwell Klinger, was drafted into the Navy after a career as a child actor, including several seasons on The Red Skelton Show, and spent two years on active duty, including in post-war Korea. McLean Stevenson, who played Colonel Blake in the show’s first three seasons, was also in the Navy.

The two men who developed M*A*S*H for television were both veterans, as well. Gene Reynolds served on a Navy Destroyer during World War II and used the experiences during a prolific career in TV producing and directing; he also directed on Hogan’s Heroes and F Troop, both military comedies, before co-creating M*A*S*H. His creative partner on the series, Larry Gelbart, was an Army vet and worked for the Armed Forces Radio.

The connection to the armed conflict meant that when they began work on the show, both the creators and their stars were determined to take the subject matter seriously. Alda said that Gelbart wrote the best TV pilot he’d ever read, but was concerned that the series might devolve into something else before long.

Alda and the producers wanted to keep the show realistic

“I was worried that it would become a high jinks at the front and that the war would just sort of exist as a pretext for silly stories,” Alda told NPR in 2019, adding that some freelance scripts for unproduced episodes, which were filled with goofy jokes, confirmed his concerns. He agreed to do the show, however, because he’d already spoken with Gelbart and Reynolds and the trio agreed that they all “wanted to do a show in which the war was seen for what it is… a place where people are badly hurt.”

It’s not that Alda was trying to recreate years of horrors that he saw on the front lines; he rarely references his own military service to this day, in part because it was so brief and uneventful, especially in comparison to the tens of thousands of Americans who died in the Vietnam and Korean Wars. “They had designs of making me into an officer but, uh … it didn’t go so well,” he told an audience in 2013. “I was in charge of a mess tent. Some of that made it into the show.”

Still, Alda said he served 200 soldiers three meals a day, and frequently, he’d catch glimpse of soldiers staring blankly at a wall, idly playing with their food, stunned by their own experiences. He didn’t know back then whether his involvement in the conflict was morally justified, but the day-to-day of life at war and all of its monotonous dangers certainly had its impact on the show.

“I understood just from doing that that when you’re in a war, it’s real. It’s the real thing. People are going to get killed or lose their arms and legs,” Alda told NPR. “And when we did M*A*S*H, I wanted to make sure that at least that understanding that I had came out — that that’s what we dealt with, and that we didn’t gloss over that and make the show about how funny things were in the mess tent.”

The original author and movie’s director hated ‘M*A*S*H’

Both the show and movie were loosely based on the novel MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors by Richard Hooker, which was the pen name for the duo of Dr. H. Richard Hornberger and writer W. C. Heinz. Hornberger served as a real army doctor in the Korean War and helped pioneer a new kind of surgery, then remembered his experiences in the vignette-heavy book published in 1968, as the Vietnam War hit its zenith.

Hornberger based Hawkeye Pierce loosely on himself and was vocal about his distaste for the show — not only did he make a pittance per episode, considering its immense popularity, but he also didn’t appreciate its anti-war sentiment. Ironically, the film’s director, Robert Altman, took immense pride in his movie’s unvarnished, unsanitized look at the carnage of war, and thus objected to the show, as well. In 2000, in a DVD commentary for his movie, he called the show “the antithesis of what we were trying to do.”

“I didn’t like the series because that series to me was the opposite of my main reason for making this film — and this was to talk about a foreign war, an Asian war, that was going on at the time,” Altman said. “And to perpetuate that every Sunday night for 12 years — and no matter what platitudes they say about their little messages and everything — the basic image and message is that the brown people with the narrow eyes are the enemy.”

The show did have its messages and, though TV couldn’t compete with the graphic images shown on the big screen at that time, it had plenty of blood and loss as well. Hawkeye and his comrades lost friends on the operating table, including Col. Blake, saw brutal injuries and put on full display the human despair so rarely portrayed in sitcoms of the era.

By M*A*S*H’s final episode, Hawkeye has a breakdown, which was as good a way as any to reflect on the exhaustion the country felt at the end of the Vietnam War, which had concluded several years into the show’s run.

Thank you for reading this post How Alan Alda’s Real-Life Military Service Influenced ‘M*A*S*H’ at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: