You are viewing the article How Accurate Is the Movie ‘Gandhi’? at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

“No man’s life can be encompassed in one telling. There is no way to give each year its allotted weight, to include each event, each person who helped to shape a lifetime. What can be done is to be faithful in spirit to the record and try to find one’s way to the heart of the man….” -Mahatma Gandhi

So reads the preamble to Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi. Released in 1982, the three-hour-plus epic encompasses more than 50 years of history and attempts to chronicle the life of the man who has come to be hailed as the father of modern India.

But how accurate is the film?

It took 20 years to get the movie made

A labor of love for director Attenborough, the preamble wording above is perhaps in some way his excuse if the verisimilitude of the project does not always add up for scholars.

“Clearly Attenborough was faced with the challenge that western audiences and audiences outside of India would only have cursory knowledge of Gandhi and the politics of the time. There are tremendous pressures there,” says author and film historian Max Alvarez of the film, which received critical praise at the time of release and would go on to win eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Actor in a Lead Role (Ben Kingsley as Gandhi) and Best Director (Attenborough).

“In the case of Gandhi, Attenborough is having to navigate the biography with the epic and with the social statement. There are all these pressures in terms of balancing a narrative script when you’re condensing 50 years of history and trying to make a good film,” adds Alvarez.

”Of course it’s a cheek, it’s an impudence to tell 50, 60, 70 years of history in three hours,” Attenborough told The New York Times when the film was released in 1982. In terms of actual historical events though, Attenborough generally succeeded. He has the major moments in the life of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi on film starting from his time as a young lawyer in South Africa to his use and preaching of nonviolent civil disobedience which helped lead India to independence from British rule. on film starting from his time as a young lawyer in South Africa to his use and preaching of nonviolent civil disobedience which helped lead India to independence from British rule.

Gandhi contains the important historical moments: Gandhi’s removal from a first-class train carriage due to his ethnicity and subsequent fight for Indian civil rights in South Africa (1893-1914); his return to India (1915); the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh Massacre in Amritsar that saw British Indian Army soldiers open fire on a gathering of unarmed men, women and children resulting in hundreds of deaths; Gandhi’s numerous arrests by the British ruling party in the hope it would diminish his teachings of noncooperation; the Salt March or Dandi March of 1930 in which, as a demonstration over the British tax on salt, Gandhi and his followers walked almost 400 miles from Ahmedabad to the sea near Dandi in order to make salt themselves; his marriage to Kasturba Gandhi (1883-1944); the end of British rule in 1947 when the British Indian Empire split into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan; and his assassination by shooting at the hands right-wing Hindu nationalist Nathuram Godse in 1948.

A British-India coproduction, Gandhi was filmed in India with many of the actual locales used, including the garden of the former Birla House (now Gandhi Smriti) where Gandhi was shot and killed.

Critics didn’t like the director’s portrayal of real people

It’s the depiction of real persons where Attenborough takes his greatest liberties and has drawn most criticism. The character of Vince Walker (Martin Sheen), the New York Times’ journalist Gandhi initially meets in South Africa and then again at the time of Salt March is fictional, inspired by real-life American war correspondent Webb Miller who did not meet the real Gandhi in South Africa, but whose coverage of the march on the Dharasana Salt Works helped change global opinion on the British rule of India. Other characters in the film such as photographer Margaret Bourke White (Candice Bergen) did in fact famously photograph Gandhi for Life magazine in 1946 and was the last person to interview Gandhi before his assassination in 1948.

Major criticism, both at the time of the film’s release and still today, centers on the portrayal of Muhammed Ali Jinnah, the father of Pakistan and champion of Muslim rights in South Asia. The film was banned in Pakistan at the time of its release and over the years, the depiction of Jinnah has come under heavy scrutiny, from the non-resemblance of actor Alyque Padamsee in the role to his depiction as an obstructionist to Gandhi’s plans. The latter disagreements loom large on film, basically ignoring Jinnah’s unwavering commitment to independence from colonial rule. “Jinnah was shown as a villain in the whole thing, skipping his entire role as Ambassador of Hindu Muslim Unity,” according to Yasser Latif Hamdani, lawyer and author of Jinnah: Myth and Reality.

Such criticism highlights the cinematic balancing act of biographical films, says Alvarez. “You’re dealing with condensing events, creating composite characters – if in real life there were a handful of politicians involved you may narrow it down to one just for the simplicity of the narrative, sometimes characters are invented for the benefit of the audience to understand better.”

Attenborough was well aware of what putting Gandhi’s life onscreen would entail, including the portrayal of real people as secondary characters to the titular. “Overriding all judgments must be, and always will be, the need to establish the acceptability and credibility – the humanity – of the leading character,” he said of the film.

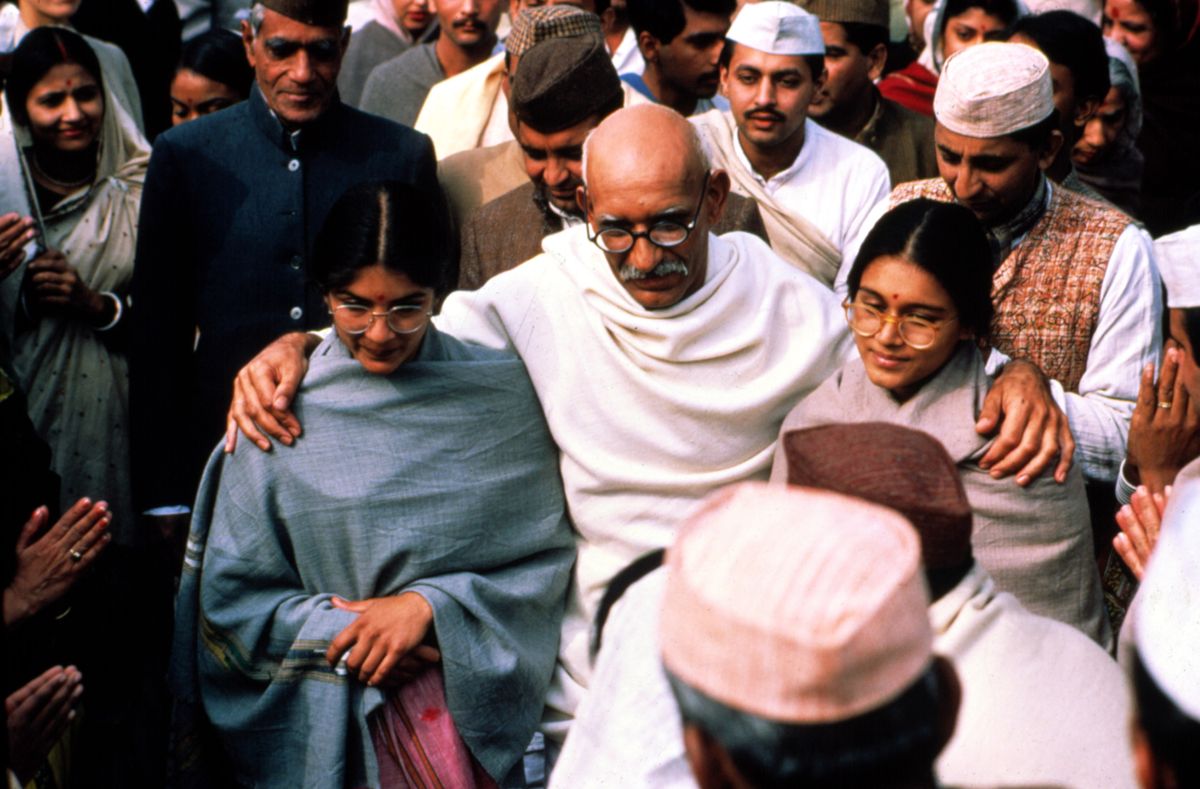

Mahatma Gandhi

and Geraldine James as Mirabehn in ‘Gandhi.’” tml-render-layout=”inline”>

Ben Kingsley wanted to focus on Gandhi’s soft side

To embody Mahatma Gandhi (Mahatma being an honorific derived from Sanskrit meaning great or high soul/spirit) Attenborough turned to British actor Kingsley, whose father came from the same area in India in which Gandhi was born. Due to time restraints of what would already be a lengthy feature film, Attenborough omitted certain parts of Gandhi’s life – some that would perhaps not be as palatable to audiences, including his estrangement with his children, his views on diet and celibacy. “Unquestionably, he was cranky,” Attenborough said of Gandhi. “He had idiosyncrasies, cranky ideas – all his attitudes toward diet and sex and medicine and education, to an extent. But they were relatively minor parts of his life, minor parts of his makeup.”

What Attenborough and Kingsley focus on is the peace-loving, soft-spoken, spiritual-leader Gandhi, whose quiet work brought radical change to the world. Gandhi, in reality, was also a British-trained lawyer and shrewd politician and manipulator. Such elements of his character are given minor precedence in the hagiographical retelling. “Kingsley’s performance definitely brought [the film] to another level,” says Alvarez. “It’s not what I would call a warts-and-all biography, you don’t really see the darker side of the man or his serious flaws. It’s basically a heroic study.” In his review of the film, Roger Ebert said Kingsley “makes the role so completely his own that there is a genuine feeling that the spirit of Gandhi is on the screen.”

Though it has been criticized for truncation of events, depictions of towering real-world figures and omissions of both historical and human scale, Gandhi succeeds as a film. Critics agree Kingsley’s performance ultimately elevated what was always a resonant and important story, as did Attenborough’s old-fashioned (even in 1982) approach to filmmaking – a grand cinematic scale that gets to the heart and reveals the humanity of, the central character. “The only kind of epics that work,” Attenborough said in 1982, ”are intimate epics.”

Thank you for reading this post How Accurate Is the Movie ‘Gandhi’? at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: