You are viewing the article How a Horrific Bus Accident Changed Frida Kahlo’s Life at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Born outside Mexico City in 1907, Frida Kahlo contracted polio at age six. The disease crippled her right leg, which grew shorter than her left and gave her a limp. Her lengthy convalescence, as well as bullying by neighborhood children, left young Kahlo isolated. She became increasingly close to her photographer father, who introduced her to his craft. She also began sketching, developing an early interest in art and was one of the first students admitted to an elite national preparatory school, where she planned to study medicine.

Bad timing led to her fateful accident

While attending school, Kahlo befriended a group of fellow left-leaning students, who dubbed themselves the Cachuchas. One of those students was Alejandro Gómez Arias, with whom Kahlo began her first serious relationship. The two exchanged passionate love letters despite physical separation caused by political unrest in Mexico — and her parents’ displeasure at the match.

As Arias and Kahlo would later recall, the couple was returning home from school on September 17, 1925, a gray, rainy, overcast day. They boarded one bus, but got off to look for an umbrella Kahlo realized she had lost. They boarded a second, more crowded bus, and took seats towards the back. Minutes later, the bus driver tried to pass in front of an oncoming electric streetcar, which crashed into the side of the bus, dragging it for a number of feet. Several passengers were killed instantly, and several later died from their injuries.

READ MORE: Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: 8 Photos of Their Colorful Love Story

Kahlo somehow miraculously survived the crash

Arias escaped with only minor injuries, but he immediately saw that Kahlo was gravely injured. An iron handrail had impaled her through her pelvis, as, she would later say, piercing “the way a sword pierces a bull.” Arias and others removed the handrail, causing Kahlo immense pain.

Kahlo’s pelvic bone had been fractured and the rail had punctured her abdomen and uterus. Her spine had been broken in three places, her right leg in 11 places, her shoulder was dislocated, her collarbone was broken, and doctors later discovered that three additional vertebrae had been broken as well.

She took up painting during her long recovery

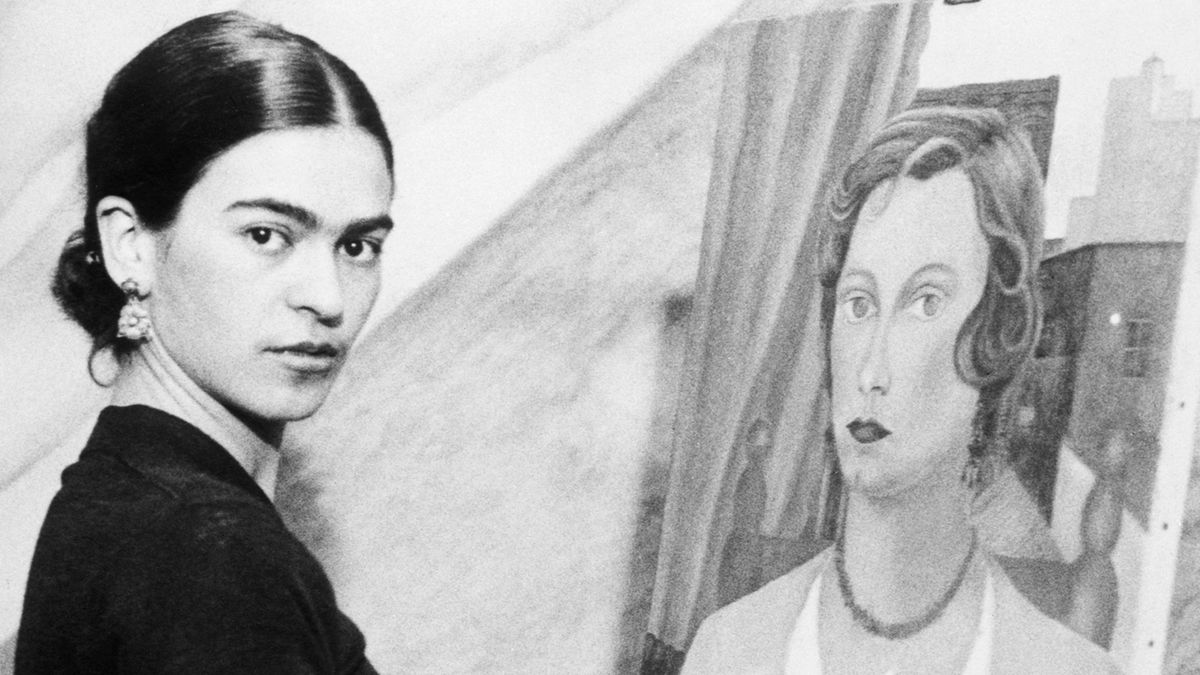

Kahlo remained in the hospital for a month, undergoing additional surgery, and then was nearly bed-ridden for several months at home, wearing a plaster cast. Although she initially hoped to combine her love of medicine and sketching to become a medical illustrator, the lingering pain from her injuries forced her to abandon the idea and drop out of school. She turned to painting to fill the hours, using a specially-made lap easel that allowed her to paint from bed. Already deeply introspective, she became her first artistic subject, using an overhead mirror in her bed’s canopy to begin painting the first in long series of self-portraits.

Kahlo never directly painted a depiction of the near-fatal bus accident, although she did create a sketch drawing of the incident. She more closely alluded to it a later work, “The Bus,” which some art historians believe shows her and a group of other passengers awaiting a bus, just moments before their fateful journey.

Adding to Kahlo’s pain was the end of her relationship with Arias, who reportedly did not visit her during her long convalesce. His absence and her loneliness left her vulnerable. When she was introduced to Mexican painter and muralist Diego Rivera in 1928 (they had briefly met several years earlier), the pair quickly began a relationship, despite a 20-year age gap. Thanks in a part to Rivera’s support of her painting — and despite his constant womanizing — the pair married in August 1929.

The crash likely contributed to Kahlo’s inability to have children

Pain from her injuries plagued Kahlo for the rest of her life. She had more than 30 additional surgeries, including one in which her back was re-broken and re-set. Kahlo turned this latest setback into an opportunity, artfully painting her body cast. Despite her increasing ill health, Kahlo and Rivera traveled widely, although their relationship was tested by mutual jealousy and infidelity (including Kahlo’s rumored affair with Marxist leader Leon Trotsky).

Kahlo desperately hoped to give Rivera a child, but several pregnancies were medically terminated when doctors feared Kahlo’s life was at risk. Another pregnancy that ended in a miscarriage became the focus of one of Kahlo’s most well-known and harrowing paintings. “Henry Ford Hospital,” painted in 1932, shows a naked Kahlo in bed, with images of a snail (meant to represent her fertility problems and slowness to have a child), a fetus and her abdomen, attached to her body by umbilical cords. Twelve years later, in 1944, Kahlo painted “The Broken Column,” in which her chest is split open to reveal the metal and leatherback brace she frequently wore in the wake of the accident.

Kahlo continued to paint her intense and often macabre self-portraits (many of which depicted her wearing traditional Mexican costumes and highlighted her prominent unibrow) for the rest of her life. She and Rivera divorced and later reconciled, but she was in failing health. In 1953, illness forced her to attend her first solo exhibition in an ambulance, and that same year, nearly 40 years after the bus accident, old wounds flared up again, leading to the amputation of a gangrenous right leg. Seemingly well aware that the end was near, she took to sketching images of angels and skeletons in her journal. She died, aged just 47, on July 13, 1954, of a pulmonary embolism.

Thank you for reading this post How a Horrific Bus Accident Changed Frida Kahlo’s Life at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: