You are viewing the article Henri Matisse: His Final Years and Exhibit at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

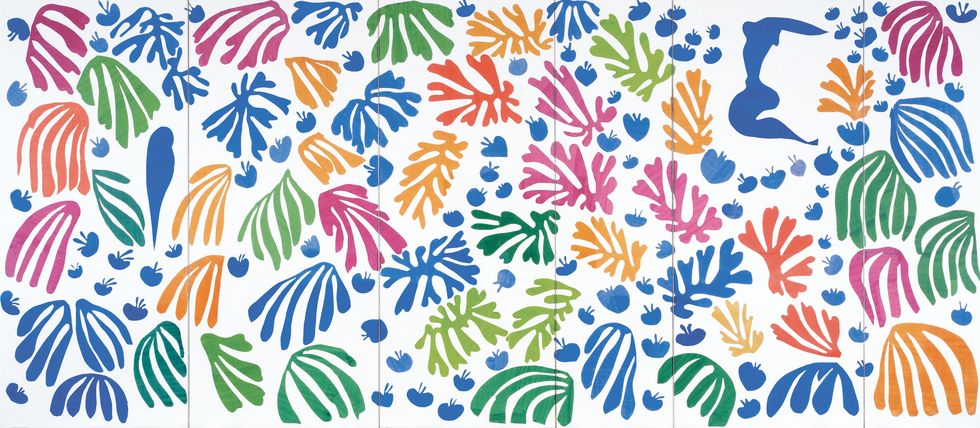

Henri Matisse created some of his best-known art in the final decade of his life, and he made it from the simplest materials: shapes cut from colorful sheets of paper. He described these “cut-out” works as “drawing with scissors,” and he used this technique for works of various sizes and subjects.

This late period of Matisse’s art is showcased in the exhibition “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The show was organized in collaboration with Tate Modern in London and features approximately 100 cut-outs borrowed from museums and private collections around the world. The cut-outs are shown alongside related sketches, archival photographs, and samples of the artist’s materials for an overall look at this late, but innovative, chapter of Matisse’s life and career.

Brush and Canvas, Scissors and Paper

Matisse initially used paper cut-outs to plot the design of works in other materials. Arranging and re-arranging small forms cut from sheets of paper, he could plan effects of composition, color, and contrast before he painted on canvas. In early experiments with this method, he employed cut-outs to visualize the stage sets he was designing for theater and ballet productions. In the 1930s paper cut-outs assisted him in creating still-life paintings and in finalizing his design for a painted mural at the Barnes Foundation museum in Pennsylvania.

Jazz and the 1940s: Cut-Outs as Works of Art

Matisse initially kept his cut-out technique a secret. In 1943, however, he began to work on Jazz, an illustrated book of cut-out designs. Jazz was published in 1947. Its main theme was the circus, and its pages reproduced Matisse’s lively paper acrobats, clowns and animals. However, there were also hints of wartime violence in the illustrations’ exploding starbursts and falling bodies.

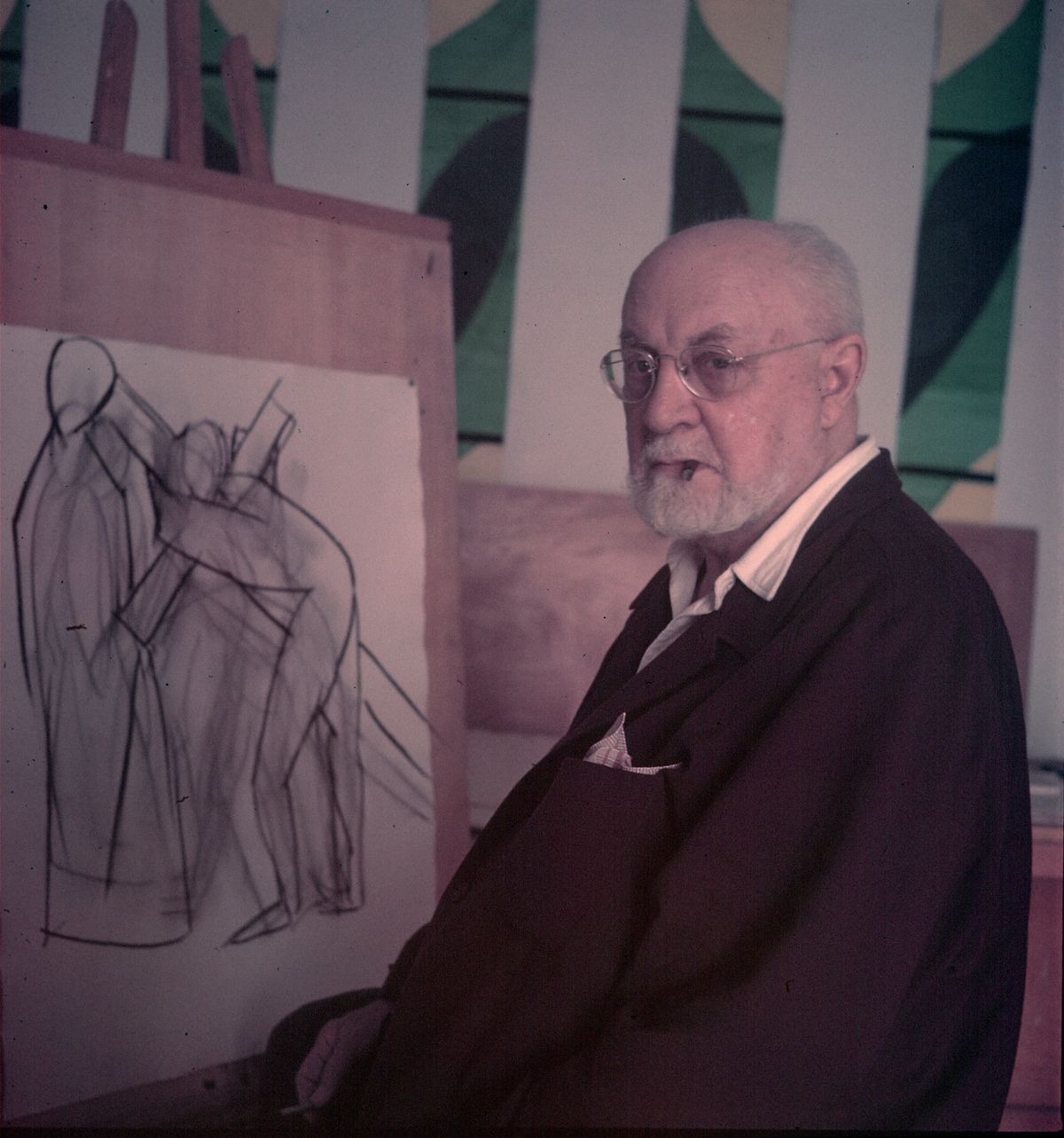

Coping with the difficulties of old age and illness in the years following World War II, Matisse nonetheless produced some of the most vibrant and dynamic works of his career. He lived and worked in southern France, in sunny studios in Vence and Nice. Following surgeries for severe intestinal disease, he was confined mostly to his bed and to a wheelchair. Working with paper turned out to be an ideal solution to his limited range of movement.

For small works, the artist’s studio assistants painted sheets of white paper with colors that he chose; Matisse then cut out shapes with a large pair of scissors and pinned them to a board, where he could adjust them until he had his final arrangement. (Two videos in the Museum of Modern Art exhibition show Matisse at work in his studio, cutting and arranging colorful bits and pieces of paper.) These smaller cut-outs included female nudes, botanical designs and geometrical compositions, as well as covers for books about his own art and about other artists, including Henri Cartier-Bresson and Guillaume Apollinaire.

A Garden, A Swimming Pool, Memories of Tahiti

For larger works, Matisse worked directly on the walls of his studio. Under his direction, his assistants would pin cut-out pieces to a wall and keep moving them as he wished. Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, the walls of Matisse’s studios and apartments were covered with carefully choreographed groupings of human figures, fruits, and flowers, all cut from paper. Many of these cut-outs are included in the show at the Museum of Modern Art, where viewers can still see their original pin-holes and the occasionally rough edges left by the blades of Matisse’s scissors.

Some of Matisse’s largest late works were inspired by places that he could no longer visit in person. For two wall-sized cut-outs of 1946, “Oceania, the Sky” and “Oceania, the Sea,” he turned to his memories of a trip to Tahiti. He described “The Parakeet and the Mermaid,” a cut-out mural that covered two walls of his studio, as “a little garden all around me where I can walk.”

“The Swimming Pool” (1950) is a cut-out that surrounds the viewer: Matisse composed it for a specific space, his own dining room in Nice. When he was no longer able to visit his favorite swimming pool in Cannes, Matisse declared, “I will make myself my own pool.” The result was a wide panel of bright blue bodies diving and swimming along a white background, designed to run around all four walls of the room. The Museum of Modern Art acquired “The Swimming Pool” in 1975, but this work has not been displayed for the past 20 years. Now, after several years of meticulous conservation, it hangs in a special gallery built to the same dimensions as Matisse’s dining room. A nearby video shows the conservation process as well as photos of “The Swimming Pool”’s original installation in Matisse’s home.

Matisse’s Final Years

In the last years of his life, Matisse came full cycle to his earlier methods, using smaller cut-outs to design works in other media. Working with cut-paper prototypes, he planned stained-glass windows and ceramic-tile wall decorations for several private homes. The project that he referred to as his “masterpiece” was the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, completed in 1951. Matisse used his cut-outs to develop many aspects of this church’s decoration, from stained-glass windows to vestments for its priests. At the Museum of Modern Art, the chapel designs are shown together in their own room, and a touch-screen displays photographs of the building’s interior and exterior.

Some of Matisse’s last works were large collages of cut-and-pasted paper, as abstract and bold as anything being made by much younger artists in the early 1950s. Matisse died in 1954 at the age of 84. His five-decade career had produced much groundbreaking art, and the current exhibition is a rare opportunity to savor the cut-outs on their own, in all their vivid glory.

Thank you for reading this post Henri Matisse: His Final Years and Exhibit at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: