You are viewing the article Harry T. Moore: Champion of the Early Civil Rights Movement at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Harry T. Moore was an educator and civil rights activist who helped establish an NAACP chapter in Brevard County, Florida. He is recognized for single-handedly increasing the number of NAACP members in Florida and for helping thousands of African Americans register to vote in the 1940s. His activism pre-dated the traditional Civil Rights Movement and he was ahead of his time in pushing for social justice and voting rights. He was especially interested in addressing unequal salaries, segregated schools, and the disenfranchisement of Black voters. Through its featured exhibition “Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom: Era of Segregation 1876-1968,” The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) exhibits artifacts that help tell Moore’s story and connect him to events that occurred in the early 20th century as well as today.

An Exceptional Student

Moore was born on November 18, 1905, in Houston, Florida (Suwannee County) to Stephen John and Rosalea Albert Moore. He came from humble beginnings and grew up in an agricultural community where his father was a farmer and storeowner. His mother worked as an insurance agent. Moore was an only child. He graduated from Florida Memorial College High School in 1924 at age 19 and was such an exceptional student that his classmates nicknamed him “Doc.” Upon graduation, he decided to pursue a teaching career in the public school system. Moore moved to Cocoa, Florida, and taught at Cocoa Junior High School where he learned firsthand that “separate but equal” was not a reality for Black students. He worked against significant disadvantages including poor facilities and limited financial resources. In 1926, he married Harriette Vyda Simms and later, the couple had two daughters, Annie Rosalea “Peaches” and Juanita Evangeline. They both worked as teachers in the public school system.

Becoming a Passionate Activist

With his strong family and tight-knit Black community to support him, Moore developed a passion for activism and spent the rest of his life-fighting discrimination. He joined the NAACP in 1934 and became president of the Brevard County branch shortly after he and Harriette founded the local organization. Moore used the NAACP platform to challenge inequality at the local and statewide level. In 1938, for example, he supported a local schoolteacher who filed for litigation against unequal pay based on race. This was one of the first lawsuits in the Deep South that challenged salary discrimination among teachers, and it was a case supported by Thurgood Marshall. Moore and the plaintiff argued that Black teacher salaries were much lower than their white people counterparts and they demanded equal pay. Even though they lost the case, some believe it paved the way for equalization of teacher salaries ten years later.

Moore continued to fight for justice and equality by organizing the Florida State Conference of the NAACP in 1941, and in 1944 he formed the Florida Progressive Voters League (chartered in 1946). He wanted to increase African American participation in the Democratic Party and could not do that through the non-partisan NAACP. He also organized protests against lynchings and police brutality and was known for speaking openly about racial injustice. When change did not immediately occur through legal measures, he took to the polls and in 1944 organized the Progressive Voters’ League. Through this organization, Moore helped register at least 100,000 Black people for the Florida Democratic Party.

Activism came at a price, however, and the Moores experienced backlash and both lost their teaching jobs in 1947. From this point forward, since he was no longer able to teach, Moore became an advocate for the prevention of and prosecution of lynching. Some suggest that Moore investigated every lynching case in the state of Florida — interviewing victims, families, and conducting his own style of investigative reporting. He also became involved in the Groveland Rape case in the summer of 1949 working directly with Thurgood Marshall. This was a high-profile case where four young African American men were accused of raping a 17-year-old white woman, Norma Padgett, in Lake County, Florida. During the hearing and in pre-trial meetings, one of the defendants, Earnest Thomas, was shot and killed by a mob. Sheriff Willis McCall shot two others during transportation to the second hearing, taking the life of Samuel Shepard and injuring Walter Irvin. The fourth defendant, Charles Greenlee, was sentenced to life in prison.

Assassination

Moore continued working toward legal and political justice after the case as the State Coordinator of Branches for the NAACP. Ku Klux Klan activity was on the rise, and on Christmas Eve in 1951, the Moores were assassinated when a bomb was placed under their bedroom. The couple had just celebrated their 25th wedding anniversary. Thankfully, both of their daughters survived the attack.

Despite there being immediate hospitals in the area, Moore was driven to a hospital 30 miles away since it was the closest facility that accepted Black patients. He never made it and died on the way there. His wife, Harriette, succumbed to her injuries a few days after the bombing.

According to historians, Moore’s death was the first assassination of a civil rights leader in the modern Civil Rights Movement. The Moores’ deaths made national news in both the Black and white people press. Harry Moore was laid to rest on January 1, 1952, in front of a large gathering, which included FBI agents who were there to protect grieving friends and family. Harriette was buried next to her husband.

Artifacts: Objects Close to the Heart

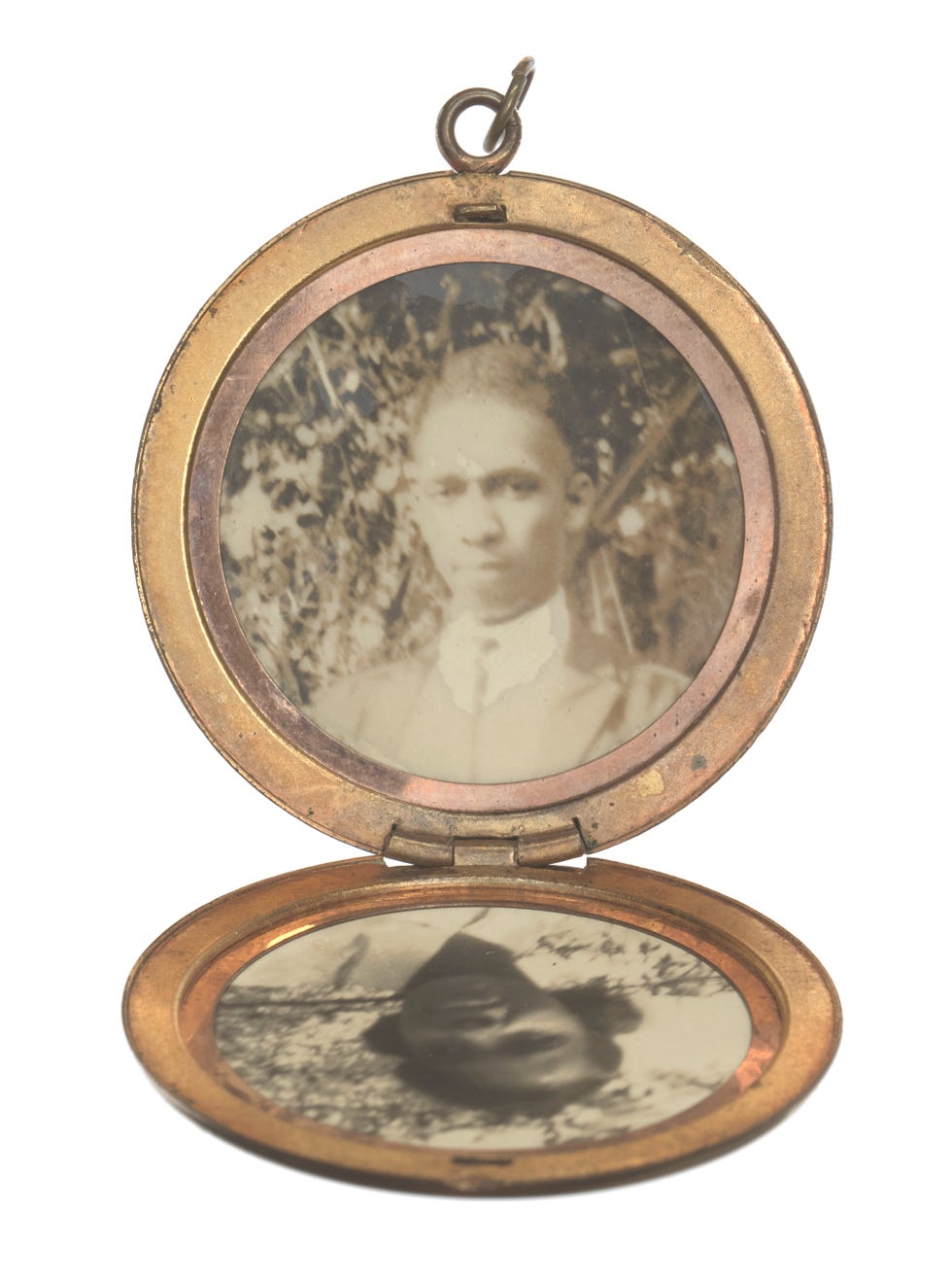

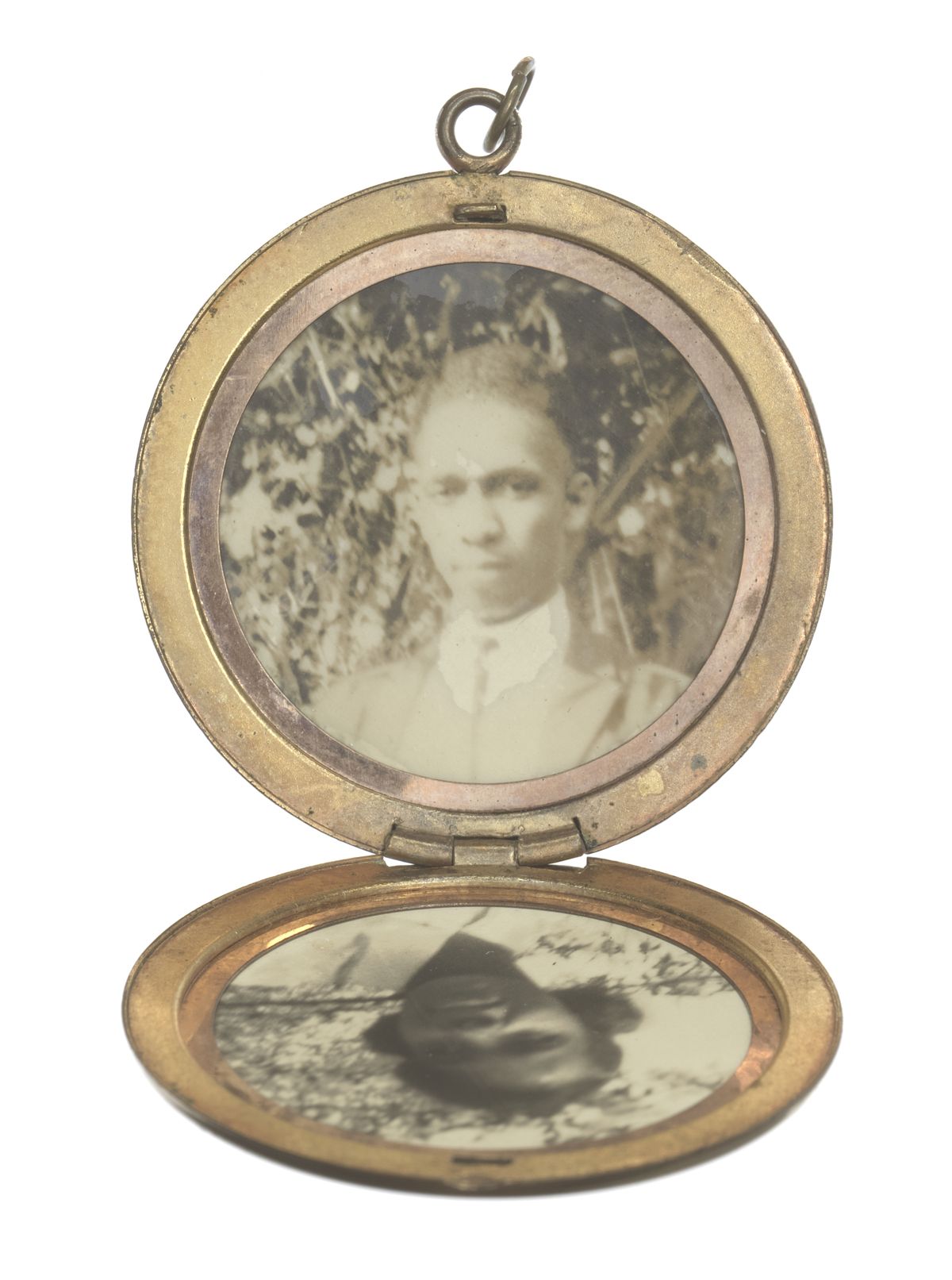

The NMAAHC displays four objects originally owned by Harriett and Harry Moore: her wristwatch and locket on a chain; his wallet and pocket watch. Their daughter Juanita Evangeline Moore donated these objects along with several documents illustrating her parents’ personal life and social activism. The locket, which is overlaid in gold metal with a floral pattern engraved on the front, contains two black and white photographs, one of Harriette and one of Harry. The backside is plain and includes a small loop to hold a necklace. The images of the couple are framed by a copper-colored ring and show them from the shoulders up. Harry is wearing a suit and Harriette is pictured wearing a light blouse. Both seem to be taken outside as tree branches are visible in the background.

The pocket watch from the Illinois Watch Company appears to be from the 1920s and is made of metal and glass. The case that houses the watch is simple brass with a ridged crown at the top. The back appears to have a faint cross hatching pattern with a small heraldic crest in the center, according to the NMAAHC object report. Both items were likely carried or worn by the couple as special jewelry.

Moore: Setting a Precedent, Posthumously Honored

Moore posthumously received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP in 1952 and in the 1990s the family and local residents worked with the state to dedicate their home to serve as a memorial/museum in their honor. Likewise, in 2012, the Cocoa, Florida post office dedicated their building to Harry T. and Harriette Moore. Their legacies are memorable, in part, because they were killed for their social justice activism more than a decade before Medgar Evers, Malcolm X or Martin Luther King Jr.

Visitors to the NMAAHC are fortunate to have the opportunity to view these two artifacts that provide a window into the Moores’ lives. We know what images Harriette kept close to her heart in the locket and we can see how Harry kept track of time. Their daughter, Juanita Evangeline, made sure that their contributions to Black education and civil rights would always be remembered. Their deaths were so significant that soon after their deaths the famous poet Langston Hughes penned a song/poem in Harry’s honor. The final lines are as follows:

When will men for sake of peace

And for democracy

Learn no bombs a man can make

Keep men [and women] from being free?. . .

And this he says, our Harry Moore,

As from the grave he cries:

No bomb can kill the dreams I hold,

For freedom never dies!

Thank you for reading this post Harry T. Moore: Champion of the Early Civil Rights Movement at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: