You are viewing the article Edith Wilson: The First Lady Who Became an Acting President — Without Being Elected at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Unofficially, America has already had what might be called a First Lady President — at least according to some historians and biographers of the controversial woman in question. And she certainly was not elected by anyone except, arguably her husband, who made their union official on December 18, 1915.

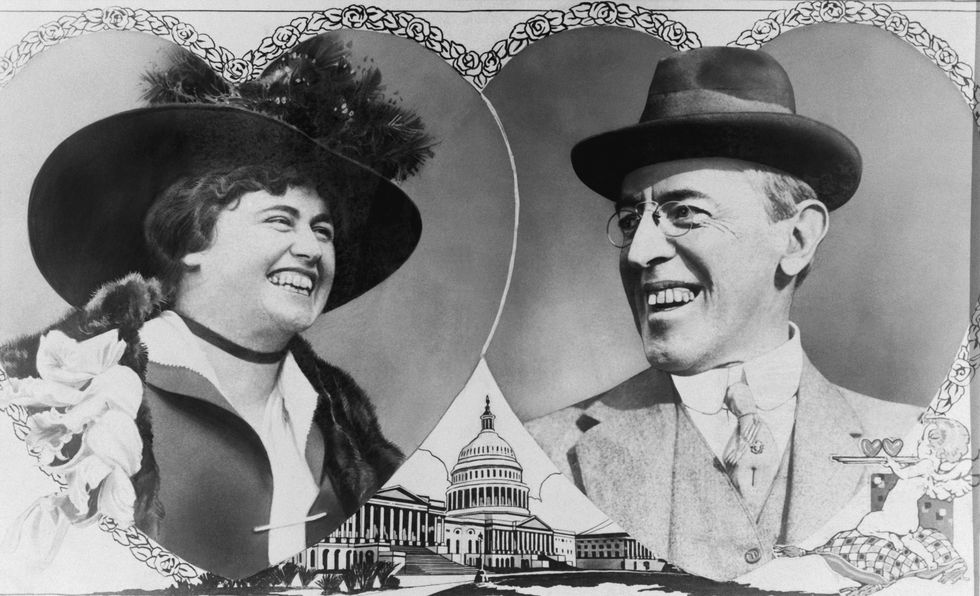

That happy occasion gave no clue that, in just three short years, Edith Bolling Galt — the widow of a Washington, D.C. jewelry store owner marrying the widowed incumbent President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson — would be accused of running the country.

Edith’s inherited wealth and status from her first marriage

The second Mrs. Woodrow Wilson seemed the least likely of women to seize control of the ultimate power to satisfy some personal desire for recognition. Born in 1872 to an impoverished family from mountainous western Virginia, she was a distant descent from Pocahontas. Never an intellect, she decided to leave Mary Washington College because her dormitory room was too cold. She instead followed an older sister and proceeded to the nation’s capital where she quickly married a much older man from a family that owned and ran the city’s oldest jewelry store.

As Mrs. Norman Galt, she gave birth to a son but the baby boy died within a few days. After 12 years of marriage, Edith found herself widowed but also wealthy. She began making frequent trips to Europe, where she developed a taste for the haute couture of the Parisian designer Worth. And when in Washington, she made a splash by becoming the first woman in town to drive her own car.

Despite her wealth and what one wag dubbed “kittenish” good looks, Edith was barred from the echelons of capital high society simply because her wealth derived from a retail store, and she was snobbishly marked as “trade.” All that changed one chilly day in the early spring of 1915.

It was love at first sight for Edith and Wilson

Edith had been out with her friend Altrude Gordon, then dating Cary Grayson, the White House physician. Among his wards were not only President Woodrow Wilson, who was still mourning the death of his wife Ellen but also the president’s cousin Helen Bones, who lived in the White House as a companion to him. That day, Bones had joined Gordon and Edith on a relaxing but muddy hike. She coaxed them back to the White House for some warm tea. As Edith put it, she “turned a corner and met my fate.”

For Wilson it was love at first sight. Soon a presidential limousine hummed most nights outside Edith’s door, ready to slip her over for romantic suppers while the next morning presidential messengers delivered suggestive love notes that flatteringly sought her apolitical opinion on issues ranging from the trustworthiness of Cabinet members to finessing diplomats as a war in Europe began to rapidly expand.

If Edith was overwhelmed when the president insisted they get married, his political advisors were downright alarmed. Not only was Wilson entrusting this woman he’d only met three months earlier with classified information, he was up for re-election in 1916. Marrying Edith barely a year after his first wife’s death, they feared, would lead to his defeat. They crafted a plan. They would generate a series of fake love letters as if written from Wilson to a Mary Peck with whom he had conducted a real love affair of the heart, and leak it to the press. It would humiliate Edith and she would flee.

Edith became a trusted advisor to Wilson

Except, she didn’t. She married the president and remembered those who had tried to rid him of her. Wilson won another term and, in April 1917, led the U.S. into World War I. By then, Edith never left his presence, working together from a private, upstairs office. He gave her access to the classified document drawer and secret wartime code, and let her screen his mail. At the president’s insistence, the first lady sat in on his meetings, after which she gave him withering assessments of political figures and foreign representatives. She denied his advisors access to him if she determined the president couldn’t be disturbed.

At war’s end, Edith escorted Wilson to Europe so he could help negotiate and sign the Treaty of Versailles and present his vision of a League of Nations to prevent any future world wars. When the Wilsons returned to the U.S., the honors of the old world gave way to the sober reality that the president would face enormous resistance among Senate Republicans in having his version of the League approved.

Wilson suffered a massive stroke and Edith stepped in

Exhausted, he nevertheless insisted on crossing the country by train to sell them on the idea, in October 1919. There was little enthusiasm. He pushed harder. Then, he collapsed from physical exhaustion. Rushed back to the White House, he suffered a massive stroke. Edith found him unconscious on the floor of his bathroom. It was soon apparent to all that Wilson could not fully function.

Edith firmly stepped in and began making decisions. Consulting with physicians, she would not even consider making her husband resign and have the vice president take over. That would only depress her Wilson. Her loving dedication to protect him by whatever means were necessary might have been admirable for a love story, but in declaring that she only cared about him as a person, not as a president, Edith revealed a selfish ignorance leading her to decide that she and the President came before the normal functioning of the executive branch of government.

The first move in establishing what she called her “stewardship” was to mislead the entire nation, from the cabinet and Congress to the press and the people. Vetting the carefully crafted medical bulletins that were publicly released, she would only permit an acknowledgment that Wilson badly needed rest and would be working from his bedroom suite. When individual cabinet members came to confer the president, they went no further than the first lady. If they had policy papers or pending decisions for him to review, edit or approve, she would first look over the material herself. If she deemed the matter pressing enough, she took the paperwork into her husband’s room where she claimed she would read all the necessary documents to him.

It was a bewildering way to run a government, but the officials waited in the West Sitting Room hallway. When she came back to them after conferring with the president, Mrs. Wilson turned over their paperwork, now riddled with indecipherable margin notes that she said were the president’s transcribed verbatim responses. To some, the shaky handwriting looked less like that written by an invalid and more like that of his nervous caretaker.

This is how she described the process she undertook:

“So began my stewardship. I studied every paper, sent from the different Secretaries or senators, and tried to digest and present in tabloid form the things that, despite my vigilance, had to go to the President. I myself never made a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs. The only decision that was mine was what was important and what was not, and the very important decision of when to present matters to my husband.”

She held her ‘stewardship’ for 17 months

Luckily, the nation faced no great, looming crisis for the period of what some dubbed her “regency” of one year and five months, from October 1919 until March 1921. Still, some of her confrontations with officials had serious consequences. When she heard that the secretary of state had convened a cabinet meeting without Wilson’s permission, she considered it an act of insubordination, and he was fired.

The most damaging irony, however, came as a result of Mrs. Wilson’s insistence that a minor British Embassy aide be fired for a bawdy joke he’d cracked at her expense – or else she would refuse the credentials of an ambassador who had come to specifically help negotiate for President Wilson’s version of the League of Nations. The ambassador refused to do so and soon returned to London. For all of the protection she had provided for her husband as a person, Edith may well have damaged what he had dreamed for as a legacy.

Until her death in 1961, the former first lady insisted that she never assumed the full power of the presidency, at best she used some of its prerogatives on behalf of a husband.

Thank you for reading this post Edith Wilson: The First Lady Who Became an Acting President — Without Being Elected at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: