You are viewing the article Creating ‘The Simpsons:’ How Matt Groening’s Own Family Inspired the Characters at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Born in 1954 in Portland, Oregon, The Simpsons creator Matt Groening had, in many ways, an idyllic childhood. As described in The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorized History, he grew up next to the old Portland Zoo, which, after reopening in a new location in 1959, became a wonderland for Groening and his friends with its abandoned animal enclosures.

He also enjoyed a happy home life, with his dad, Homer, mom, Margaret, and four siblings, including younger sisters Lisa and Maggie. It was Homer, a cartoonist and filmmaker, who showed his precocious son that a career of creative fulfillment was possible.

But the conformity of a suburban existence soon proved dull, even to a young Groening. Acting out in school, he recalled having to write “I must be quiet in class” 500 times on at least one occasion and having his doodles torn up by teachers.

As a third-grader, he entered a short-story contest set up with the premise that a child walks into his attic, bumps his head and then knows what he wants to become when he grows up. In Groening’s version, the boy dies from his head injury and returns as a ghost every Halloween, a morbid tale that surprisingly became the winning entry.

Groening delivered biting commentary as a school paper editor

By high school, Groening had learned to channel his subversive leanings in a manner that engaged his classmates. He ran for student body president on the Teens for Decency ticket, with the tongue-in-cheek slogan, “If you’re against decency, then what are you for?” Again, to his surprise, he won.

Groening went on to the liberal Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, where he butted heads with the more extreme countercultural types that populated the campus. He gleefully zinged their sensibilities after becoming editor of the school paper, at one point instigating a petition that condemned his satirization of communal life, while also training his ire on mainstream targets like the Washington state legislature.

He also invited the off-the-wall submissions of campus cartoonists, finding himself inspired by the original works of fellow undergrad Lynda Barry.

His ‘Life in Hell’ comic was inspired by his struggles in Los Angeles

After graduating in 1977, Groening headed to Los Angeles with the idea of pursuing a writing career. He found some work along those lines, whipping up slogans for horror movies, but also took on a series of jobs that included chauffeur, dishwasher and record store clerk to make a living.

Groening’s rough-and-tumble early days in Tinseltown provided endless fodder for a comic he titled Life in Hell, featuring the anthropomorphic rabbit Binky. Along with mailing the comics to friends and family back in Portland, he attempted to sell his stapled-together books from his record store.

The artist saw his first non-self-published comic appear in a 1978 issue of Wet magazine. That year, he also began working for the alternative-weekly newspaper the L.A. Reader through an ever-shifting array of responsibilities that included reporter, distribution manager, punk rock critic and assistant editor. He finally added staff cartoonist to his resume when Life in Hell first appeared in the paper in the spring of 1980.

The strip gained traction after a shift in tone, with Binky becoming less preachy and more of a victim of the cultural and social forces that browbeat dissidents into submission. With a developing cast of characters that included Binky’s girlfriend Sheba, his one-eared son Bongo and the gay entrepreneurs Akbar and Jeff, and recurring components like “The 16 Types of Sisters” and “The 9 Secret Love Techniques That Could Possibly Turn Men Into Putty in Your Hands,” the minimally drawn but meticulously written Life in Hell found its niche between the underground comics and mainstream fare.

His girlfriend built a business around his artwork

Groening’s career got a boost in the early 1980s when the L.A. Reader hired sales rep Deborah Caplan, who observed that the Life in Hell strips were “a major selling point” of the paper. After the two became romantically involved, she established a business to promote her future husband’s work, negotiating syndication arrangements with other publications and a book deal with Pantheon.

Meanwhile, Groening was up to his old tricks of rocking the boat, writing silly reviews of bands based on their publicity photos and even making up phony acts to cover. He was fired from the L.A. Reader in 1986, after writing a letter to the editor over a fellow writer’s dismissal, but by then Life in Hell was already appearing in other alt-weeklies and providing extra income through merchandise sales.

Furthermore, the once-struggling artist was about to be presented with the business offer that would change his life forever.

Groening created ‘The Simpsons’ for ‘The Tracey Ullman Show’

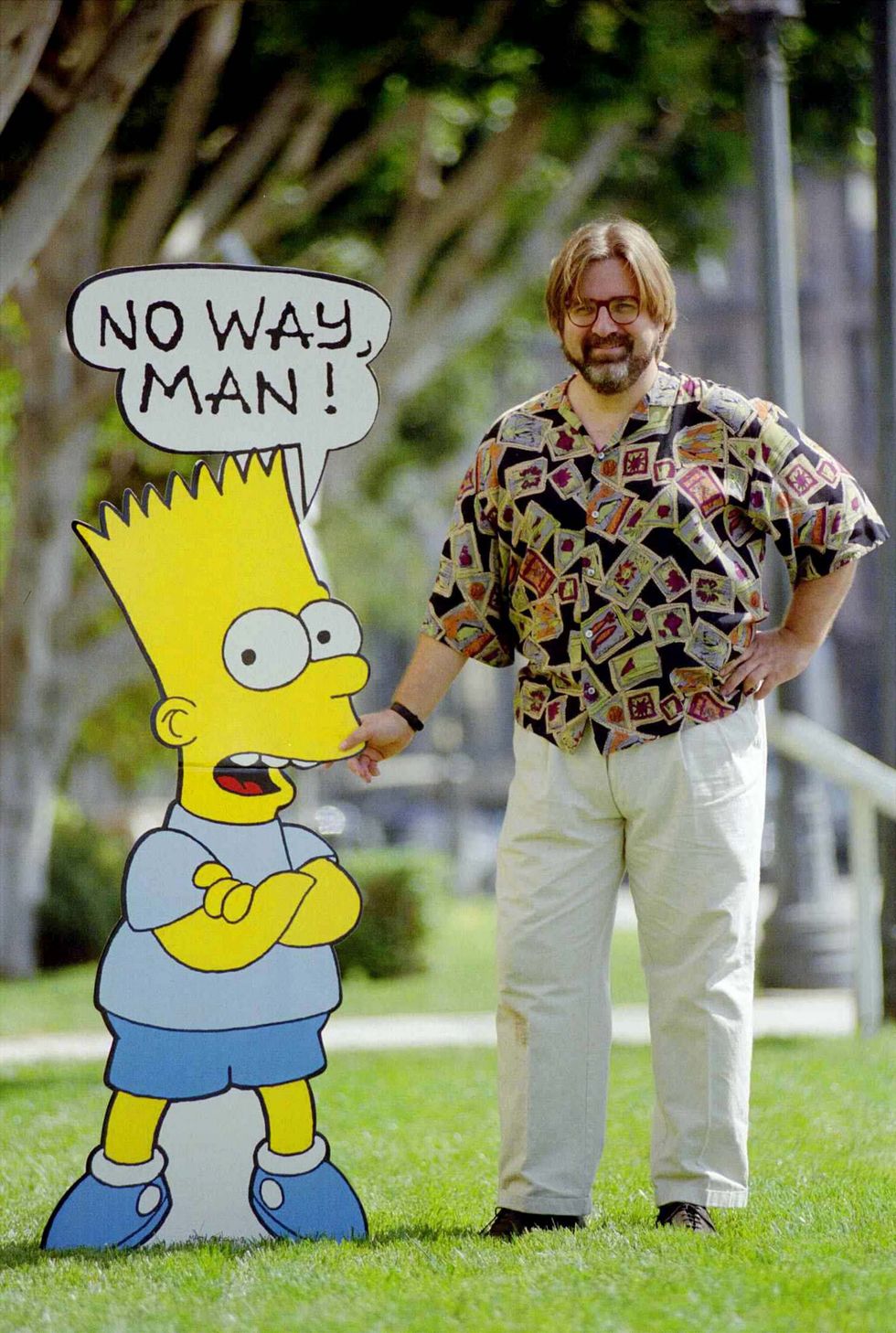

In 1987, producers of the soon-to-be-launched sketch comedy program The Tracey Ullman Show, headed by the legendary James L. Brooks, contacted Groening about developing short animated cartoons to air between skits. Realizing that he would lose the rights to his Life in Hell characters with the deal, Groening quickly created a new cartoon family named after his own siblings and parents, albeit with a “Bart” in lieu of a character named after himself.

The early iteration of The Simpsons was a crude, Neanderthal version of the family that would become ubiquitous in pop culture; both Bart and Lisa were troublemakers, and Homer was a barely controlled cauldron of rage. But the short clips were a hit with fans, and producers began exploring a standalone series as Tracey Ullman floundered in the ratings.

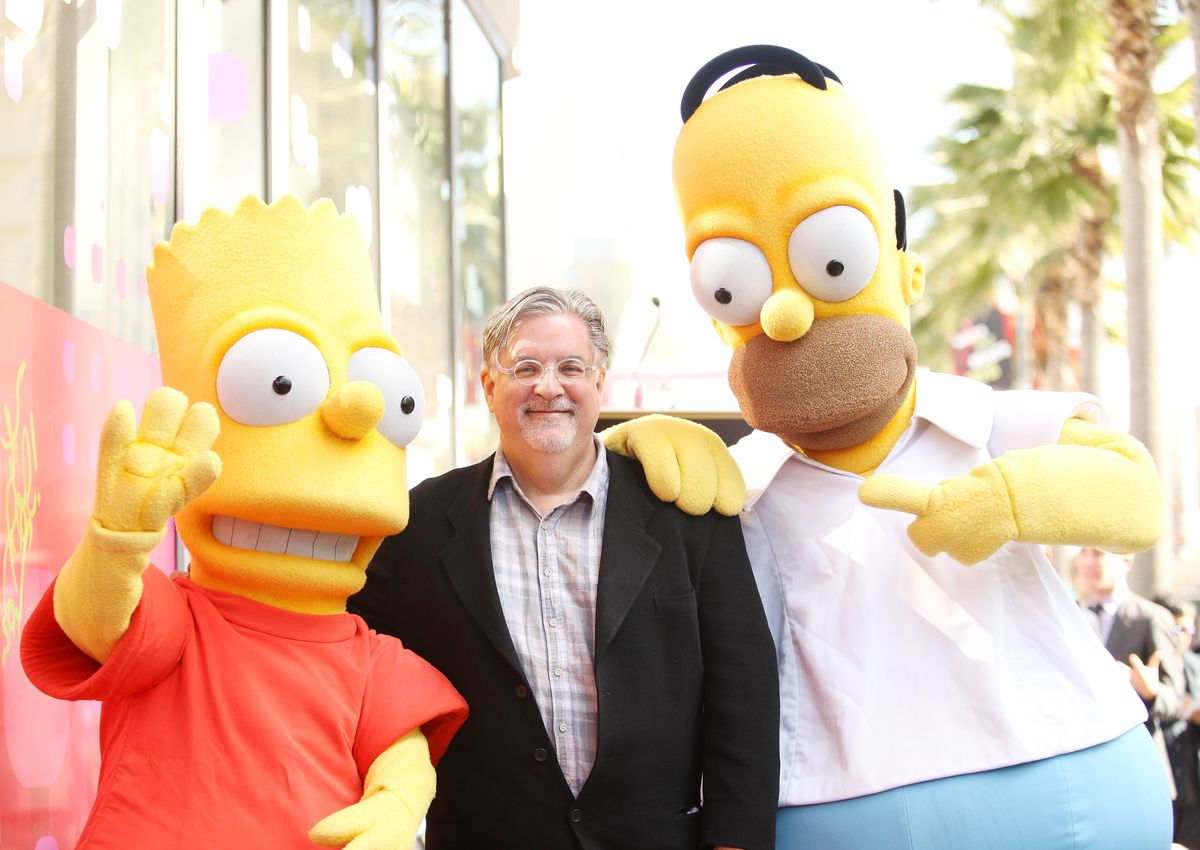

Brooks selected his longtime colleague Sam Simon to help Groening develop the animated series, and The Simpsons dynasty began on December 17, 1989, when the first episode aired. However, the show’s collection of memorable supporting characters and winking, multilayered nods to popular culture, arguably owes more to Simon and the original stable of writers than to Groening.

Yet Groening’s DNA is all over the show, from the characters named after the streets of his hometown (Flanders, Lovejoy, etc.), to his selection of Danny Elfman to compose the iconic theme song, to his insistence on the cartoon adhering to the normal laws of physics despite the liberties taken with continuity.

Most importantly, The Simpsons retained the subversive undercurrent that has driven its creator since he was a bored grade school student. “If there’s a message that runs through the show,” he told The New York Times in 2001, well after he had become wealthy and influential beyond his wildest dreams, “it’s that maybe the authorities don’t have your best interests at heart.”

Thank you for reading this post Creating ‘The Simpsons:’ How Matt Groening’s Own Family Inspired the Characters at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: