You are viewing the article Black History Month: Photos of Frederick Douglass & His ‘North Star’ on His 200th Birthday at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Frederick Douglass is arguably the most highly recognized African American man of the 19th century. Although born enslaved, he learned to read and write, and after he escaped, went on to become a public speaker, editor, recruiter for the Union Army, bank president, minister and consul general to Haiti. Many consider Douglass an important literary figure as well because he published countless speeches and three autobiographies: The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845); My Bondage and My Freedom (1855); and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881 and 1882).

These accounts provide a clear sense of his growth, struggles, and some of his most intimate thoughts and feelings. Douglass was also the founder and editor of The North Star, an abolitionist newspaper, an 1848 edition of which is held in the collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) and is on display there in the exhibition, “Slavery and Freedom.” Additionally, Douglass has been recognized as the most photographed man of his day, and one of those original photographs is in the collection of NMAAHC.

The Awakening of Douglass

Frederick August Washington Bailey was born in Talbot County, Maryland, probably in 1818. Like most enslaved people, Frederick Douglass did not know his exact birthday, so he chose February 14 because his mother referred to him as “my valentine.” He was the offspring of a white man who he believed was his enslaver and Harriet Bailey, an enslaved woman. Douglass had at least three older siblings and two younger sisters. As with all enslaved families, separation was inevitable. Raised by his grandparents, Betsy and Isaac Bailey, he had fond memories of his childhood until he witnessed the beating of his Aunt Hester when he was six years old. Douglass was fortunate to learn to read as an adolescent from Sophia Auld, the enslaver he went to live with in Baltimore. His desire for freedom only grew through literacy and after experiencing physical violence at the hands of Edward Covey, a cruel man to whom Douglass was sent to work for by the Aulds.

In 1838, he liberated himself by fleeing to New York where he married Anna Murray, a free Black woman he had fallen in love with prior to his escape. With freedom came the power to change his name to Douglass. He and Anna had five children together (Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Redmond, and Annie). His freedom was purchased from Thomas Auld by his anti-slavery friends and supporters in 1845 for $711. By today’s standards that is equivalent to approximately $21,200.

Giving Voice to Equal Rights

Douglass became very active in the anti-slavery movement and joined the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society as a public speaker. Working alongside abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips, Douglass and his story to freedom put him in high demand. In 1847 Douglass published his first newspaper, The North Star. One year later he advocated for women’s rights and worked with suffragists including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, even attending the First Women’s Rights Convention held in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. In the years before the Civil War, he continued to work with abolitionists including John Brown and Harriet Tubman. During the war, he advocated for Black troops to enlist.

His wife died in 1882, and within a year, he married his secretary, Helen Pitts. He spent some of the 1890s working with Ida B. Wells on anti-lynching campaigns and continued to push for women’s suffrage. On the day of his death, February 20, 1895, he had attended a meeting of the National Council of Women, returned home to tell his wife about it, had a heart attack and collapsed on the floor of his home. Five days later nearly 2,000 guests attended the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., to pay their respects to the great leader.

‘A Picture Makes Its Own Way in the World’

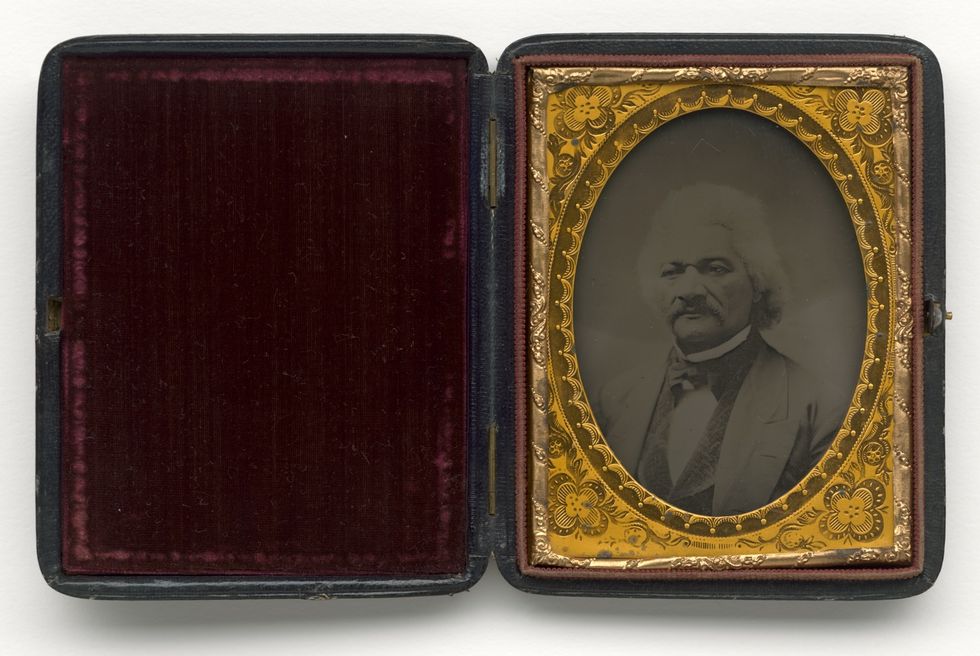

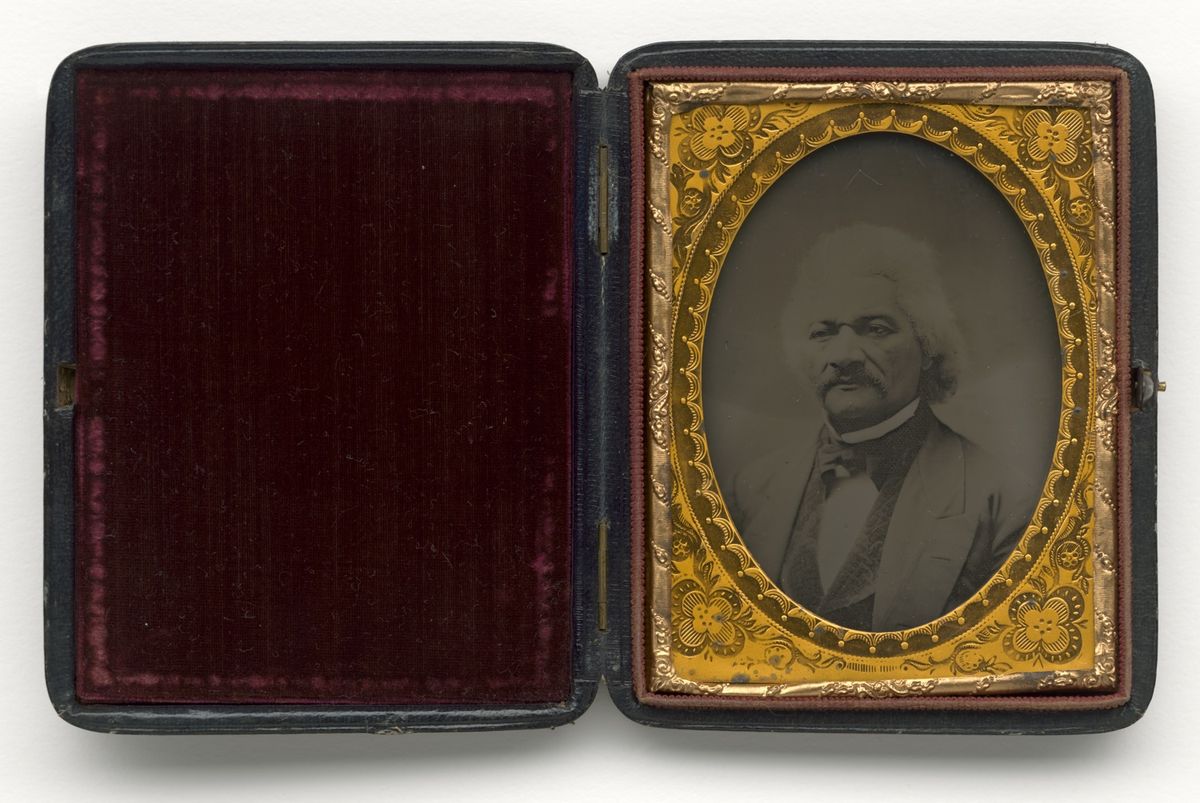

Douglass sat for this photograph, which was taken sometime between 1855 and 1865, during the time period he was publishing his second narrative and editing his anti-slavery newspaper. Scholars suggest that he is one of the most photographed persons of the 19th century with about 160 images in circulation. Douglass thought deeply about the importance of pictures and shared his thoughts in four lectures delivered during the Civil War years. He remarked, “Pictures, like songs, should be left to make their own way in the world. All they can reasonably ask of us is that we place them on the wall, in the best light, and . . . allow them to speak for themselves.”

What does this image say about him? Encased in a collodion and silver frame with glass photographic plates, this small 4×3 inches black and white image is centered in an oval mat with gold and yellow flower etchings. Enclosed in a “folding leather case” with maroon velvet and stitching, it shows Douglass “wearing a jacket, waistcoat, and a bowtie.” His body is positioned facing right and he has a full head of grey hair and a thick salt and pepper mustache. Douglass’ determined look coincides with his ideas about photographs which included the thought that the “universality of pictures must exert a powerful, though silent, influence upon the ideas and sentiment of present and future generations.” The museum purchased this artifact from an auction house in 2010. Museum Specialist Mary Elliott reminds us that Douglass was strategic about using “photography to disseminate his message.”

The Power of His Words

The second item (above) is the September 8, 1848, edition of The North Star vol. 1 no. 37, Douglass’ anti-slavery newspaper. The masthead reads: “Right is of no sex; truth is of no color, God is the Father of us all — and all are brethren.” The North Star was published for 175 consecutive weeks, from December 3, 1847, to April 17, 1851. In this issue, Douglass, along with co-editor Martin R. Delany, explain that “The object of the NORTH STAR will be to attack SLAVERY in all its forms and aspects; advocate UNIVERSAL EMANCIPATION; exalt the standard of PUBLIC MORALITY; promote the moral and intellectual improvement of the COLORED PEOPLE, and hasten the day of FREEDOM …” This issue also contains information about colonization, international news from France, Ireland and several other countries, as well as poetry, and advertisements for clothing and hair-cutting services. In 1851 the newspaper merged with the Liberty Party Paper and changed its name to the Frederick Douglass Paper (1851-1860).

Douglass’ Legacy

Douglass was a prolific writer, abolitionist, editor, orator, suffragist, and political leader. His story from slavery to freedom is remarkable, exhibiting strength of character and great resolve. Having these two artifacts allows us to see Douglass in his own making, an image he sat for and a newspaper he edited. Because he produced so much writing, we have the opportunity to read first-hand accounts of his life and to study the issues he deemed crucial to society. Booker T. Washington summed up Douglass’ legacy in the opening of his 1906 biography of Douglass with the following sentence: “The life of Frederick Douglass is the history of American slavery epitomized in a single human experience.”

The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture. The Museum’s nearly 40,000 objects help all Americans see how their stories, their histories, and their cultures are shaped by a people’s journey and a nation’s story.

Thank you for reading this post Black History Month: Photos of Frederick Douglass & His ‘North Star’ on His 200th Birthday at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: