You are viewing the article An Inside Look at Albert Einstein’s Personal Life at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

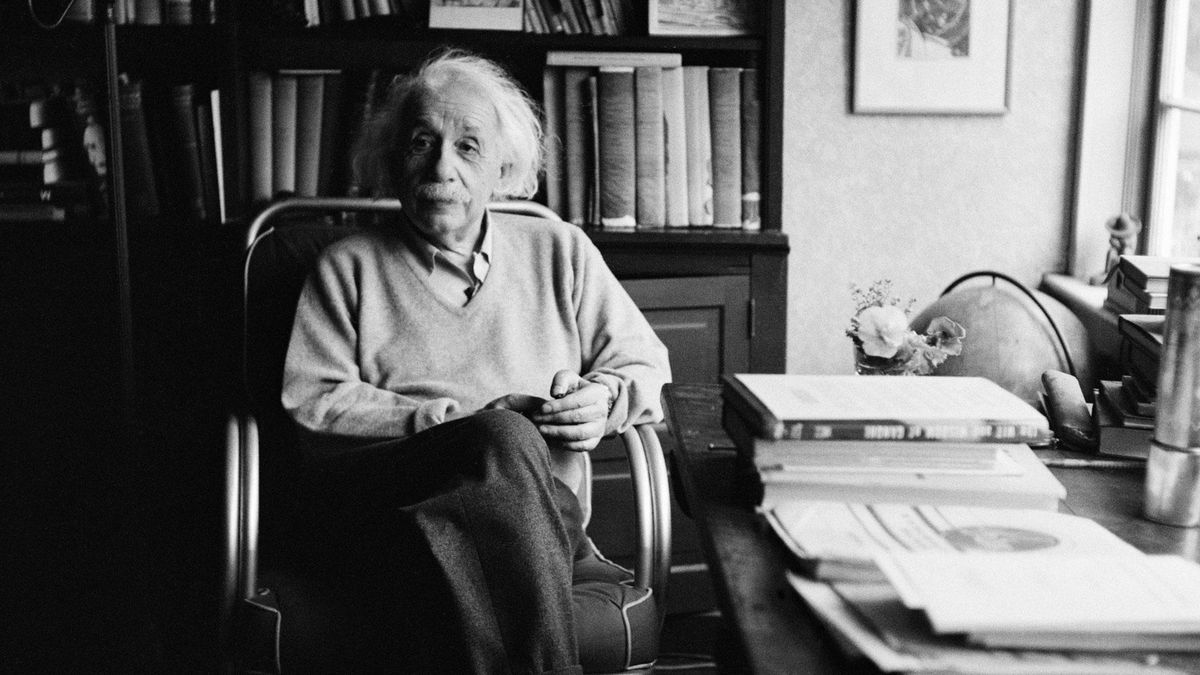

Up until his death, Albert Einstein was on the hunt for one simple, cohesive theory that could explain space and time. Pragmatic and disciplined in his work, he was nothing but in his personal life. In fact, he was a bit of a mess.

Einstein was married twice, first to his former student Mileva Maric, and then to his cousin Elsa. His marriages were marred with affairs, along with women lavishing gifts on him. In previous known letters, Einstein expressed the misery he experienced in his first marriage, describing Mileva as a depressed and jealous woman. Of the two sons he had with her, he had even confessed he wished his younger son Eduard, whom had schizophrenia, was never born. As for his second wife Elsa, he called their relationship a union of convenience.

New letters revealed a different side of Einstein

Biographers used such correspondence to describe Einstein as a cold and cruel husband and father, but in 2006 the release of close to 1,400 previously unknown letters from the scientist offered a more well-rounded view of his relationship to both his wives and family.

In the more recent letters, we find that Einstein had compassion and empathy for his first wife and their children, offering a portion of his 1921 Nobel Peace Prize winnings to support them. Of his son Eduard, Einstein wrote how much he enjoyed receiving his poetry and pictures and added: “The more refined of my sons, the one I considered really of my own nature, was seized by an incurable mental illness.” As for his second marriage, Einstein apparently discussed his affairs openly with Elsa and also kept her apprised of his travels and thoughts.

“My lectures here. . .are already behind me. This morning quartet — very beautiful, like old times,” he wrote her in 1921. “The first violin is played by a youth of 80 years! Soon I’ll be fed up with the relativity. Even such a thing fades away when one is too involved with it.”

Einstein recognized his personal failures

For her reasons, Elsa stayed with Einstein, despite his flaws, and explained her views about him in a letter: “Such a genius should be irreproachable in every respect. But nature does not behave this way, where she gives extravagantly, she takes away extravagantly.”

But it’s not to say Einstein didn’t have a conscience about his personal failures. Writing to a young gentleman, the scientist admitted as much. “What I admire in your father is that, for his whole life, he stayed with only one woman. This is a project in which I grossly failed, twice.”

For all of Einstein’s immortalized genius, his love life proved he was very much a human tethered to Earth.

Thank you for reading this post An Inside Look at Albert Einstein’s Personal Life at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: