You are viewing the article Andrew Jackson at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

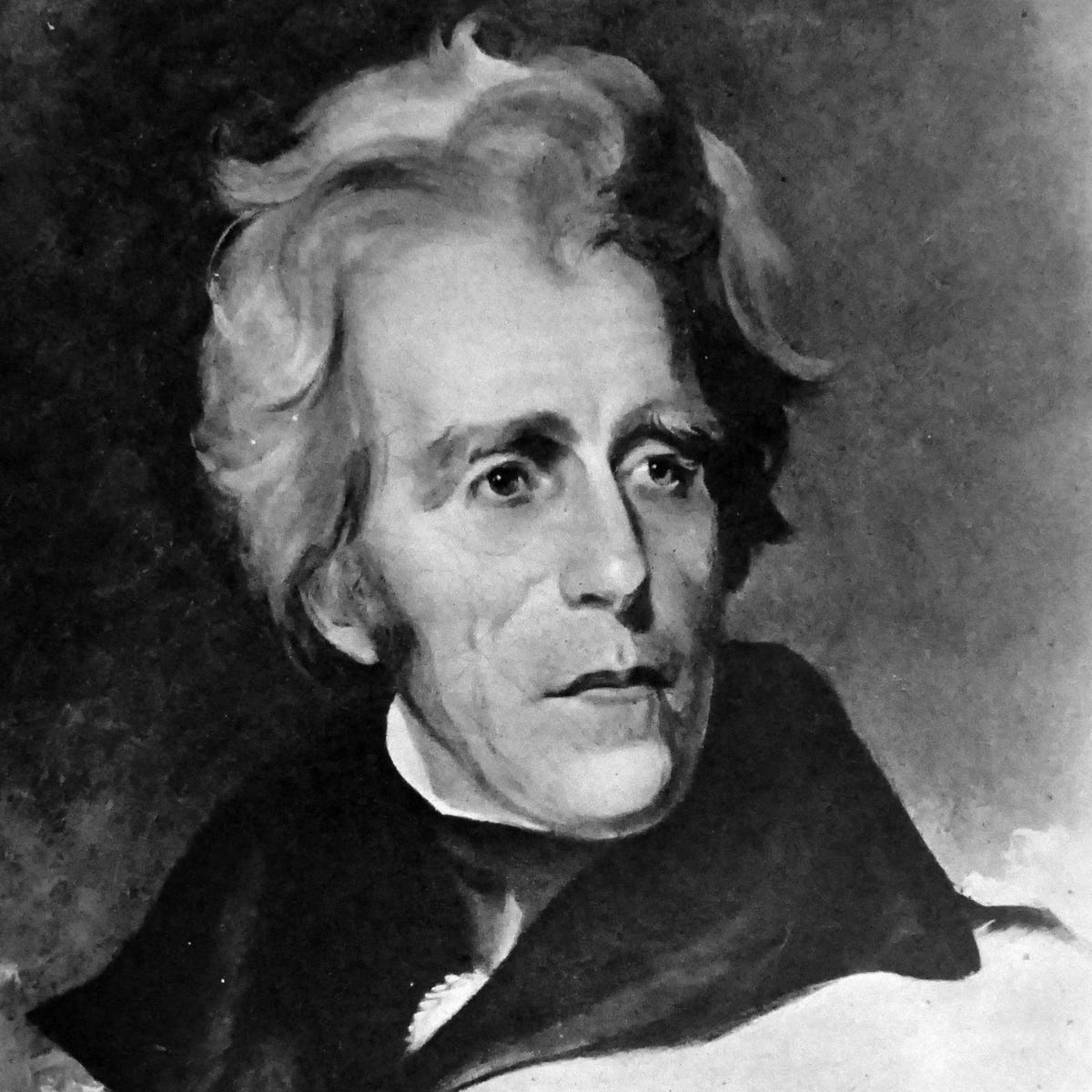

Andrew Jackson, born on March 15, 1767, was the seventh President of the United States, serving from 1829 to 1837. Known for his strong leadership and controversial policies, Jackson played a significant role in shaping the course of American history. Often hailed as a champion of the common man, his presidency was marked by a commitment to expanding democracy and confronting powerful elites. However, his legacy is also marred by his treatment of Native Americans and his aggressive stance on many issues. In this essay, we will delve into the life and presidency of Andrew Jackson, examining both his accomplishments and his flaws, and seeking to understand his impact on the nation.

(1767-1845)

Who Was Andrew Jackson?

A lawyer and a landowner, Andrew Jackson became a national war hero after defeating the British in the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. Jackson was elected the seventh president of the United States in 1828. Known as the “people’s president,” Jackson destroyed the Second Bank of the United States, founded the Democratic Party, supported individual liberty and instituted policies that resulted in the forced migration of Native Americans. He died on June 8, 1845.

Early Life

Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, to Andrew and Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson, Scots-Irish colonists who emigrated from Ireland in 1765. Though Jackson’s birthplace is presumed to have been at one of his uncles’ houses in the remote Waxhaws region that straddles North Carolina and South Carolina, the exact location is unknown since the precise border had yet to be surveyed. Jackson’s birth came just three weeks after the sudden death of his father at the age of 29.

Growing up in poverty in the Waxhaws wilderness, Jackson received an erratic education in the years before the Revolutionary War came to the Carolinas. After his older brother, Hugh, died in the Battle of Stono Ferry in 1779, the future president joined a local militia at age 13 and served as a patriot courier. Captured by the British along with his brother Robert in 1781, Jackson was left with a permanent scar from his imprisonment after a British officer gashed his left hand and slashed his face with a sword because the young boy refused to polish the Redcoat’s boots. While in captivity the brothers contracted smallpox, from which Robert would not recover.

Orphaned at Age 14

A few days after the British authorities released the brothers in a prisoner exchange arranged by their mother, Robert died. Not long after his brother’s death, Jackson’s mother died of cholera contracted while she nursed sick and injured soldiers. At the age of 14, Jackson was orphaned, and the deaths of his family members during the Revolutionary War led to a lifelong antipathy of the British.

Raised by his uncles, Jackson began studying law in Salisbury, North Carolina, in his late teens. He was admitted to the bar in 1787, and soon after, the 21-year-old Jackson was appointed prosecuting attorney in the western district of North Carolina, an area that is now part of Tennessee. He moved to the frontier settlement of Nashville in 1788 and eventually became a wealthy landowner from the money he accumulated from a thriving law practice. In 1796, Jackson was a member of the convention that established the Tennessee Constitution and was elected Tennessee’s first representative in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was elected to the U.S. Senate the following year but resigned after serving only eight months. In 1798, Jackson was appointed a circuit judge on the Tennessee superior court, serving in that position until 1804.

Military Career, the War of 1812

Although he lacked military experience, Jackson was appointed a major general of the Tennessee militia in 1802. During the War of 1812, he led U.S. troops on a five-month campaign against the British-allied Creek Indians, who had massacred hundreds of settlers at Fort Mims in present-day Alabama. The campaign culminated with Jackson’s victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814, which resulted in the killing of some 800 warriors and the eventual procurement by the United States of 20 million acres of land in present-day Georgia and Alabama. After this military success, the U.S. military promoted Jackson to major general.

Without specific instructions, Jackson led his forces into the Spanish territory of Florida and captured the outpost of Pensacola in November 1814, before pursuing British troops to New Orleans. Following weeks of skirmishes in December 1814, the two sides clashed on January 8, 1815. Although outnumbered nearly two-to-one, Jackson led 5,000 soldiers to an unexpected victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans, the last major engagement of the War of 1812.

Nickname ‘Old Hickory’

Dubbed a national hero, Jackson received the thanks of Congress and a gold medal. He was also popular among his troops, who said that Jackson was “as tough as old hickory wood” on the battlefield, earning Jackson the nickname “Old Hickory.”

Given command of the Army’s southern division, Jackson was ordered back into service during the First Seminole War at the end of 1817. Perhaps exceeding his orders, he invaded Spanish-controlled Florida, captured St. Mark’s and Pensacola once again, executed two British subjects for secretly assisting the Indians in the war and overthrew West Florida Governor José Masot.

Adams-Onis Treaty

His actions drew a strong diplomatic rebuke from Spain, and many in Congress and in the cabinet of President James Monroe called for his censure, but Secretary of State John Quincy Adams came to Jackson’s defense. Spain ceded Florida to the United States under the 1819 Adams-Onis Treaty, and Jackson held the post of Florida’s military governor for several months in 1821.

Senator Andrew Jackson

Jackson’s military exploits made him a rising political star, and in 1822 the Tennessee Legislature nominated him for the presidency of the United States. To boost his credentials, Jackson ran for and won election to the U.S. Senate the following year.

In 1824, state factions rallied around “Old Hickory,” and a Pennsylvania convention nominated him for the U.S. presidency. Though Jackson won the popular vote, no candidate gained a majority of the Electoral College vote, which threw the election to the House of Representatives. Speaker of the House Henry Clay, who had finished fourth in the electoral vote, pledged his support to Jackson’s primary opponent, Adams, who emerged victorious. At first Jackson accepted the defeat, but when Adams named Clay as secretary of state, his backers decried what they saw as a backroom deal that became known as the “Corrupt Bargain.”

Presidency

After a bruising campaign, Jackson — with South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun as his vice-presidential running mate — won the presidential election of 1828 by a landslide over Adams. With his election, Jackson became the first frontier president and the first chief executive who resided outside of either Massachusetts or Virginia.

Jackson was the first president to invite the public to attend the inauguration ball at the White House, which quickly earned him popularity. The crowd that arrived was so large that furniture and dishes were broken as people jostled one another to get a look at the president. The event earned Jackson the nickname “King Mob.”

Accomplishments

New Political Party

The negative reaction to the House’s decision resulted in Jackson’s re-nomination for the presidency in 1825, three years before the next election. It also split the Democratic-Republican Party in two. The grassroots supporters of “Old Hickory” called themselves Democrats and would eventually form the Democratic Party. Jackson’s opponents nicknamed him “jackass,” a moniker that the candidate took a liking to — so much so that he decided to use the symbol of a donkey to represent himself. That symbol would later become the emblem of the new Democratic Party.

Jackson’s Veto Power

After becoming president, Jackson did not submit to Congress in policy-making and was the first president to assume command with his veto power. While prior presidents rejected only bills they believed unconstitutional, Jackson set a new precedent by wielding the veto pen as a matter of policy.

Still upset at the results of the 1824 election, he believed in giving the power to elect the president and vice president to the American people by abolishing the Electoral College, garnering him the nickname the “people’s president.” Campaigning against corruption, Jackson became the first president to widely replace incumbent officeholders with his supporters, which became known as the “spoils system.”

Second Bank of the United States

In perhaps his greatest feat as president, Jackson became involved in a battle with the Second Bank of the United States, a theoretically private corporation that actually served as a government-sponsored monopoly. Jackson saw the bank as a corrupt, elitist institution that manipulated paper money and wielded too much power over the economy. His opponent for re-election in 1832, Henry Clay, believed the bank fostered a strong economy. Seeking to make the bank a central campaign issue, Clay and his supporters passed a bill through Congress to re-charter the institution. In July 1832, Jackson vetoed the re-charter because it backed “the advancement of the few at the expense of the many.”

The American public supported the president’s views on the issue, and Jackson won his 1832 re-election campaign against Clay with 56 percent of the popular vote and nearly five times as many electoral votes. During Jackson’s second term, attempts to re-charter the bank fizzled, and the institution was shuttered in 1836.

Jackson’s Vice President: John C. Calhoun

Another political opponent faced by Jackson in 1832 was an unlikely one — his own vice president. Following the passage of federal tariffs in 1828 and 1832 that they believed favored Northern manufacturers at their expense, opponents in South Carolina passed a resolution declaring the measures null and void in the state and even threatened secession. Vice President Calhoun supported the principle of nullification along with the notion that states could secede from the Union.

Although he believed the tariff to be too high, Jackson threatened to use force to enforce federal law in South Carolina. Already replaced by New York’s Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s former secretary of state, on the 1832 ticket, Calhoun protested and became the first vice president in American history to resign his office on December 28, 1832. Within weeks, a compromise was passed that included a modest reduction in the tariff along with a provision that empowered the president to use the armed forces if necessary to enforce federal laws. A crisis was averted, but the battle over states’ rights foreshadowed the Civil War three decades later.

During Jackson’s second term, he was the target of the first presidential assassination attempt in American history. As he was leaving a memorial service for a congressman inside the U.S. Capitol on January 30, 1835, deranged house painter Richard Lawrence emerged from the crowd and pointed a single-shot gold pistol at the president. When the gun failed to shoot, Lawrence pulled out a second pistol, which also misfired. The infuriated Jackson charged the shooter and hammered him with his cane while bystanders subdued the attempted assassin. The English-born Lawrence, who believed he was an heir to the British throne and owed a massive amount of money by the U.S. government, was found not guilty by reason of insanity and confined to institutions for the rest of his life.

Controversial Decisions

Trail of Tears

Despite his popularity and success, Jackson’s presidency was not without its controversies. One particularly troubling aspect of it was his dealings with Native Americans. He signed and implemented the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which gave him the power to make treaties with tribes that resulted in their displacement to territory west of the Mississippi River in return for their ancestral homelands.

Jackson also stood by as Georgia violated a federal treaty and seized nine million acres inside the state that had been guaranteed to the Cherokee tribe. Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in two cases that Georgia had no authority over the tribal lands, Jackson refused to enforce the decisions. As a result, the president brokered a deal in which the Cherokees would vacate their land in return for territory west of Arkansas. The agreement resulted after Jackson’s presidency in the Trail of Tears, the forced relocation westward of an estimated 15,000 Cherokee Indians that claimed the lives of approximately 4,000 who died of starvation, exposure and illness.

Dred Scott Decision

Jackson also nominated his supporter Roger Taney to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Senate rejected the initial nomination in 1835, but when Chief Justice John Marshall died, Jackson re-nominated Taney, who was subsequently approved the following year. Justice Taney went on to be best known for the infamous Dred Scott decision, which declared African Americans were not citizens of the United States and as such lacked legal standing to file a suit. He also stated that the federal government could not forbid slavery in U.S. territories. In his career as Supreme Court Justice, Taney would go on to swear in Abraham Lincoln as president.

While Jackson’s supporters formed the Democratic Party, his opponents also coalesced in a new political party, united in their antipathy of the president and his policies. Adopting the same name as anti-monarchists in England, the Whig Party formed during Jackson’s second term to protest what it saw as the autocratic policies of “King Andrew I.”

The Whig party failed to win the 1836 presidential election, which was captured by Martin Van Buren. Jackson, however, left his successor with an economy ready to crater. “Old Hickory” believed that paper money did not benefit the common man and that it allowed speculators to buy huge swaths of land and drive prices artificially high. Having taken a financial loss from devalued paper notes himself, Jackson issued the Specie Circular in July 1836, which required payment in gold or silver for public lands. Banks, however, could not meet the demand. They began to fail, and the ensuing Panic of 1837 devastated the economy during the course of Van Buren’s one-term presidency.

Andrew Jackson’s Wife

When Jackson arrived in Nashville in 1788, he met Rachel Donelson Robards, who, at the time, was unhappily married to but separated from Captain Lewis Robards. Rachel and Andrew married before her divorce was officially complete — a fact that was later brought to light during Jackson’s 1828 presidential campaign. Although the couple had legally remarried in 1794, the press accused Rachel Jackson of bigamy.

Andrew Jackson Duel

Jackson’s willingness to engage his and his wife’s many attackers earned him a reputation as a quarrelsome man. During one incident in 1806, Jackson even challenged one accuser, Charles Dickinson, to a duel. Despite being wounded in the chest by his opponent’s shot, Jackson stood his ground and fired a round that mortally wounded Dickinson. “Old Hickory” carried the bullet from that fight — along with that from a subsequent duel — in his chest the rest of his life.

The Jacksons never had any biological children but adopted three sons, including a pair of Native American infant orphans Jackson came upon during the Creek War: Theodore, who died in early 1814, and Lyncoya, who was found in his dead mother’s arms on a battlefield. The couple also adopted Andrew Jackson Jr., the son of Rachel’s brother Severn Donelson.

On December 22, 1828, two months before Jackson’s presidential inauguration, Rachel died of a heart attack, which the president-elect blamed on the stress caused by the nasty campaign. She was buried two days later, on Christmas Eve.

Death

After completing his second term in the White House, Jackson returned to Tennessee, where he died on June 8, 1845, at the age of 78. The cause of death was lead poisoning caused by the two bullets that had remained in his chest for several years. He was buried in the plantation’s garden next to his beloved Rachel.

Jackson continues to be widely regarded as one of the most influential U.S. presidents in history, as well as one of the most aggressive and controversial. His ardent support of individual liberty fostered political and governmental change, including many prominent and lasting national policies.

Andrew Jackson’s House: The Hermitage

In 1798, Jackson acquired an expansive plantation in Davidson County, Tennessee (near Nashville), called the Hermitage. At the outset, nine African American enslaved peoples worked on the cotton plantation. By the time of Jackson’s death in 1845, however, approximately 150 slaves labored in the Hermitage’s fields.

Jackson and President Trump

Jackson was among the favored predecessors of the 45th U.S. president, Donald Trump, who hung a portrait of Old Hickory in the White House. Ironically, that portrait earned a prominent position behind Trump during a November 2017 event to honor the Navajo Code Talkers — Native Americans who assisted the U.S. Marines during World War II by transmitting encrypted messages through their native language.

Videos

Related Videos

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Jackson

- Birth Year: 1767

- Birth date: March 15, 1767

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Andrew Jackson was the seventh president of the United States. He is known for founding the Democratic Party and for his support of individual liberty.

- Industries

- Politics and Government

- Astrological Sign: Pisces

- Interesting Facts

- President Andrew Jackson joined the military to fight in the Revolutionary War at age 13.

- President Andrew Jackson was the first president to ride on a train in 1833.

- Because his hometown of Waxhaws was on the border between North Carolina and South Carolina, President Andrew Jackson is the only commander-in-chief whose exact state of birth is unknown.

- Death Year: 1845

- Death date: June 8, 1845

- Death State: Tennessee

- Death City: Davidson County

- Death Country: United States

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn’t look right,contact us!

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Andrew Jackson Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/andrew-jackson

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: November 16, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

QUOTES

- Any man worth his salt will stick up for what he believes right, but it takes a slightly better man to acknowledge instantly and without reservation that he is in error.

- As the general government encroaches upon the rights of the states, in the same proportion does it impair its own power and detract from its ability to fulfill the purposes of its creation.

- When it was seen that war was waged upon the state, that the knife and the tomahawk were held over the heads of women and children, that peaceable citizens were murdered, it was time to make resistance.

- We must and will be victorious—we must conquer as men who owe nothing to chance; and who, in the midst of victory, can still be mindful of what is due to humanity.

- When men of high standing attempt to trample upon the rights of the weak, they are the fittest objects for example or punishment. In general, the great can protect themselves, but the poor and humble require the arm and shield of the law.

- The individual who refuses to defend his rights when called by his government deserves to be a slave, and must be punished as an enemy of his country and friend to her foe.

- I will die in the last ditch before I would yield a foot…or see the Union disunited.

- Without obedience, without order, without discipline, all your efforts are in vain. The brave man, inattentive to his duty, is worth little more to his country than the coward who deserts her in the hour of danger.

- For myself, to have been instrumental in the deliverance of such a country is the greatest blessing that Heaven could confer.

- As long as our government is administered for the good of the people, and is regulated by their will; as long as it secures to us the rights of person and of property, liberty of conscience, and of the press, it will be worth defending.

- When called by my country to the station which I occupy, it was not without a deep sense of its arduous responsibilities, and a strong distrust of myself, that I obeyed the call.

- One man with courage makes a majority.

- The bank is trying to kill me, but I will kill it!

- Elevate those guns a little lower.

In conclusion, Andrew Jackson was a highly controversial figure in American history. While he is often revered as a champion of the common man and a defender of democracy, his presidency was also marked by a number of questionable actions and decisions. His policies towards Native Americans and his support of slavery are deeply troubling, and his approach to the economy led to detrimental consequences for many Americans. Nevertheless, his influence on the presidency cannot be denied, as he expanded executive power and set a precedent for future leaders. Andrew Jackson’s legacy is a complex one, with both positive and negative aspects, and it is important to critically examine and evaluate his actions in order to fully understand the impact he had on American society and politics.

Thank you for reading this post Andrew Jackson at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. Andrew Jackson biography

2. Andrew Jackson presidency

3. Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act

4. Andrew Jackson and the nullification crisis

5. Andrew Jackson’s role in the Battle of New Orleans

6. Andrew Jackson’s involvement in the Bank War

7. Andrew Jackson’s impact on the Supreme Court

8. Andrew Jackson’s controversial legacy

9. Andrew Jackson and the spoils system

10. Andrew Jackson’s relationship with Native American tribes