You are viewing the article Bob Dylan Was Going to Quit Music But Then Wrote One of His Biggest Hits at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

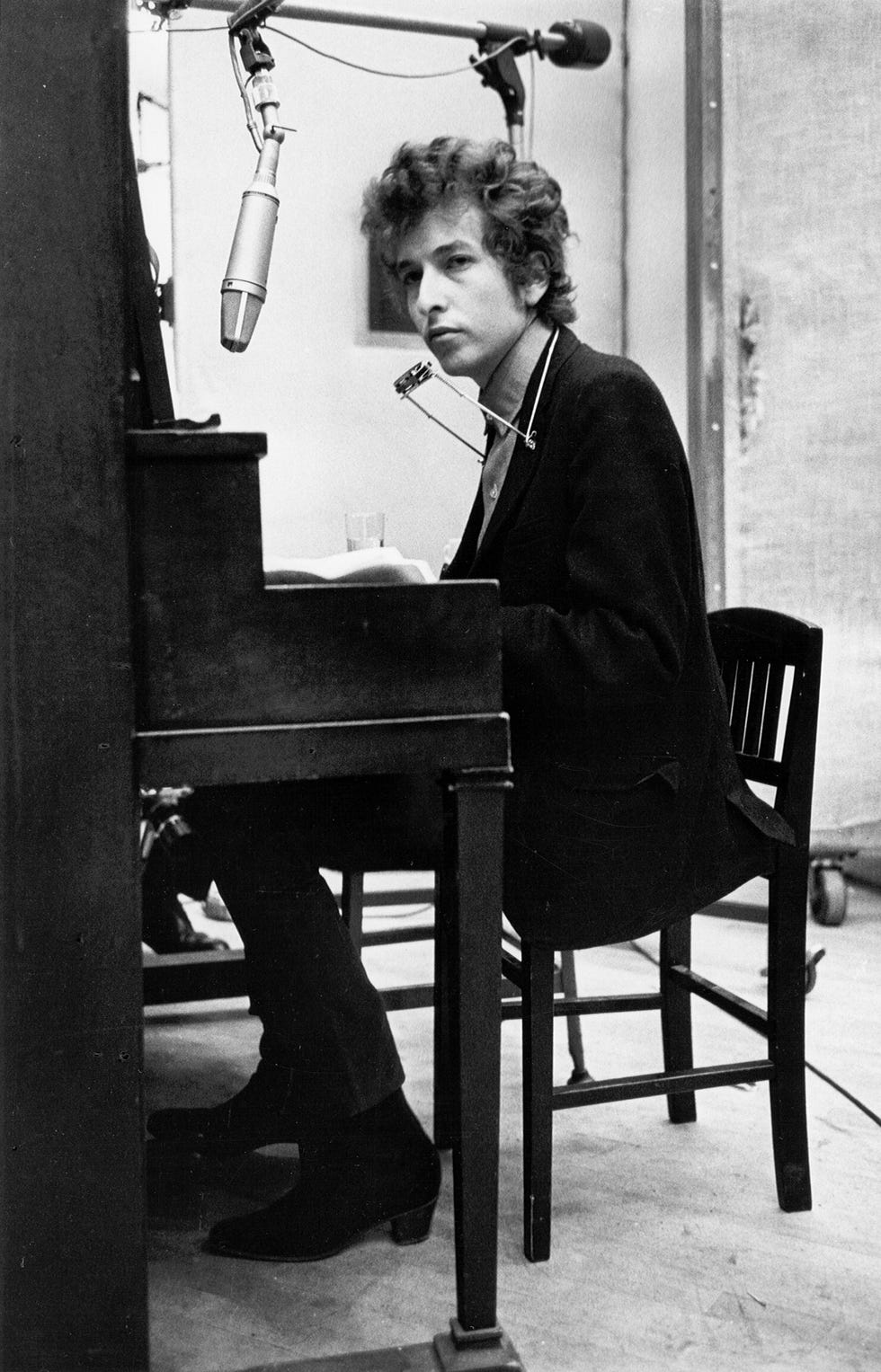

It didn’t take long for Bob Dylan to become a star, but it required a few very whirlwind and unprecedented years for the folk-rock icon to actually feel like he was doing something worthwhile and in control of his life and career. And if it weren’t for one rambling writing session and an experiment at the piano that led to his generation-defining hit “Like a Rolling Stone,” Dylan may have wound up as a blip in music history instead of one of the most influential and enigmatic artists of all-time.

Dylan felt ‘drained’ from his music

Dylan had just celebrated his 22nd birthday when his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, hit record stores. The record, a historic achievement in many ways, propelled Dylan on from the folk clubs of Greenwich Village toward national recognition. It also established a new kind of politically charged, rock-infused folk song. More success followed, with another big studio album, a prominent place in the civil rights movement and even a tour of England that made him a star in Europe.

Still, Dylan wasn’t feeling fulfilled. He argued with Ed Sullivan and blew off the biggest talk show in the United States, got criticism (and accusations of smoking dope) for mouthing off during performances and felt alienated from the folk and political scenes that had been so central to his identity. Even with a slew of iconic hits already under his belt — including “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “The Times They Are a-Changin’” and “Subterranean Homesick Blues” — he wasn’t even sure that he wanted to stay on his ever-rising trajectory.

“I was going to quit singing,” he told Playboy in an interview published in February 1966. “I was very drained, and the way things were going, it was a very draggy situation… I was playing a lot of songs I didn’t want to play. I was singing words I didn’t really want to sing. It’s very tiring having other people tell you how much they dig you if you yourself don’t dig you.”

The urge to quit hit in the spring of 1965, when Dylan was finishing up a tour of England, which was later featured in D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary Don’t Look Back. During a stop in London, Dylan even told his manager that he was going to quit. It didn’t help that his newest album, Bringing It All Back Home, released that February, earned middling reviews and backlash for its introduction of electric guitar and a backing band, a major departure from his folk style.

“Like a Rolling Stone” was never meant to be a song

Once Dylan returned from England, he went back up to Woodstock, New York, where he’d started taking refuge from the demands of the public and press. During his retreat, he began writing again, putting anything and everything that came into his mind onto the page.

“It was 10 pages long,” he later told the Saturday Evening Post. “It wasn’t called anything, just a rhythm thing on paper all about my steady hatred directed at some point that was honest. In the end, it wasn’t hatred, it was telling someone something they didn’t know, telling them they were lucky. Revenge, that’s a better word.”

In some interviews, Dylan said the document went 20 pages. Regardless of length, the Kerouacian stream-of-consciousness was supposedly meant to be the beginning of a novel. Then inspiration struck.

“I had never thought of it as a song, until one day I was at the piano, and on the paper it was singing, ‘How does it feel?’ in a slow motion pace, in the utmost of slow motion following something,” Dylan said in the Saturday Evening Post interview. “I wrote it. I didn’t fail. It was straight.”

It was something of a revelation for Dylan, who began mining his pile of notes for lyric materials. What followed was what Dylan would later call a “breakthrough,” with the resultant song clarifying his purpose, passion, and the course of his career.

“I’d never written anything like that before and it suddenly came to me that was what I should do,” he told the CBC in an interview a few years later. “After writing that I wasn’t interested in writing a novel, or a play. I just had too much, I want to write songs.”

“Like a Rolling Stone” wasn’t directly political like some of Dylan’s other songs, but it captured the anger, cynicism and revolutionary spirit of a generation. The song’s four verses poked at a once-affluent and comfortable princess, whom he called “Miss Lonely,” and chronicled her socioeconomic decline. “You better take your diamond ring, you better pawn it babe,” Dylan warned, suggesting that further comeuppance was headed her way.

There have been attempts over the years to figure out who “Miss Lonely” stood in for, with suggestions that it could have been Joan Baez or Edie Sedgewick, who may or may not have had an affair with Dylan during that period. Dylan had little love lost for Andy Warhol’s Factory scene, and the people he describes in the song certainly match up to those involved in that art collective.

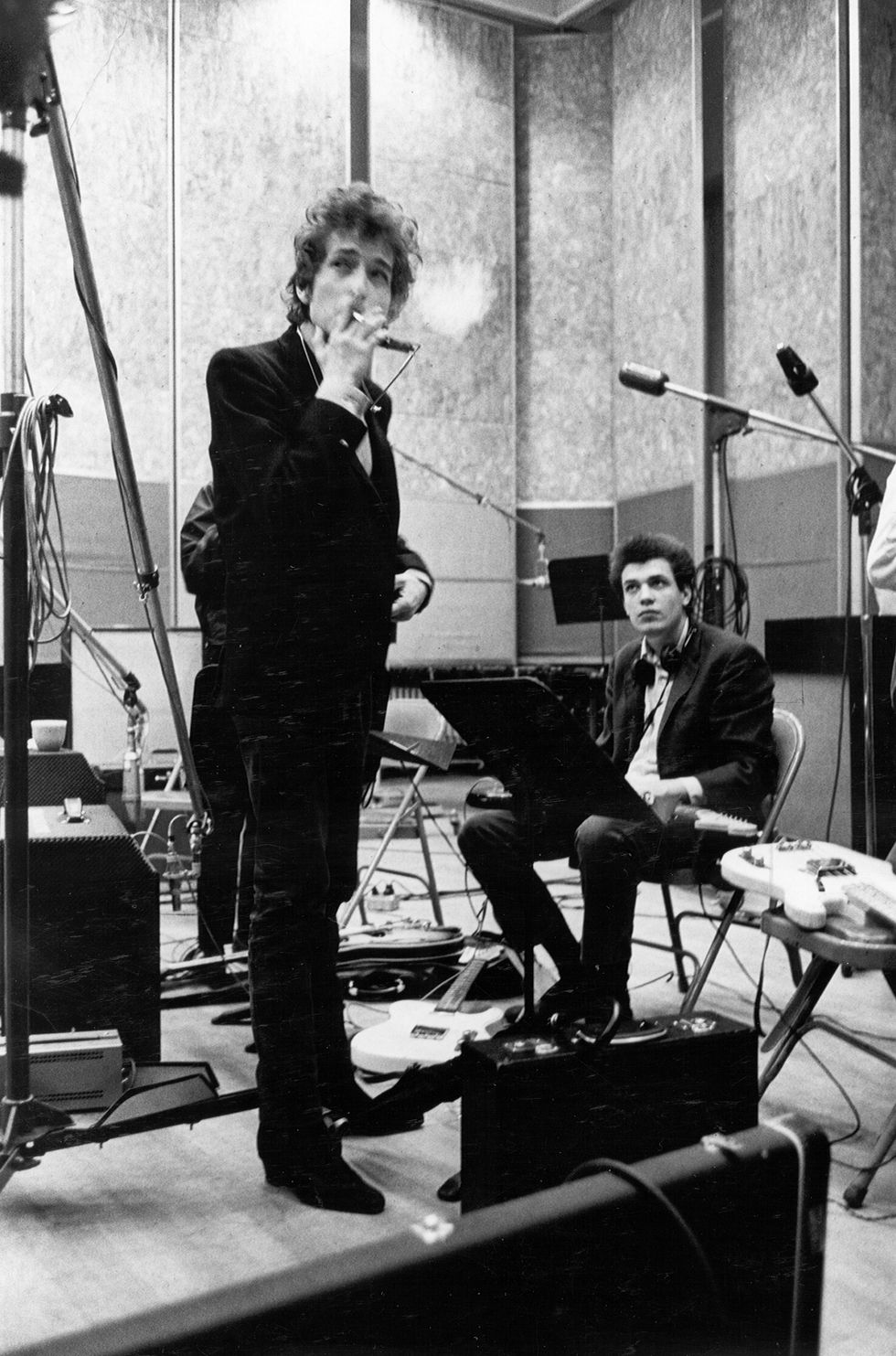

Dylan continued his work with a backing band, a big departure from his earlier work

Dylan invited a blues guitarist named Mike Bloomfield, with whom he had little history, to come up to Woodstock to help him complete the song. When they began, it was still raw and unfinished, requiring experimentation and rearrangement. Years later, when the original lyrics sheet was auctioned off, it revealed that words and phrases were swapped out for others and the chorus was initially buried on the fourth page.

“I figured he wanted blues, string bending, because that’s what I do,” Bloomfield later said. “He said, ‘Hey, man, I don’t want any of that B.B. King stuff.’ So, OK, I really fell apart. What the heck does he want? We messed around with the song. I played the way that he dug, and he said it was groovy.”

“Like a Rolling Stone” became Dylan’s highest-charting single at that point, reaching No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100, and revived his passion for music. Later on, he’d speak about it in spiritual terms.

“It’s like a ghost is writing a song like that,” Dylan said in a 2004 interview. “It gives you the song and it goes away, it goes away. You don’t know what it means. Except the ghost picked me to write the song.”

Thank you for reading this post Bob Dylan Was Going to Quit Music But Then Wrote One of His Biggest Hits at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: