You are viewing the article How Alexander Graham Bell Helped Helen Keller Defy the Odds at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Eclipsed by his fame as the inventor of the telephone, phonograph, metal detector and early forms of the hydrofoil (among other machines) is the extensive work that Alexander Graham Bell did with the deaf throughout his life. Indeed, it is both his personal family history and his interest in and study of voice and speech that would directly lead him to his most famous accomplishments. And despite the world-changing, historical significance of his contributions as an inventor, it was this work with the deaf that, later in life, Bell himself would describe as “more pleasing to me than even recognition of my work with the telephone.”

In recent decades, Bell has been vilified by some members of the deaf community, who point to his eugenics-tinged opinions on deafness and his successful efforts to ban the use of sign language in deaf education. However, others contend that Bell’s efforts, although misguided, were in fact well-intentioned, and there is perhaps no aspect of his life that better supports this claim than his longtime friendship with Helen Keller.

Bell had a deep fascination with voice and deafness

Born healthy on June 27, 1880, at 18 months Keller suffered a fever that left her blind and deaf. Although she developed a rudimentary sign language with which to communicate, as a child she was isolated, unruly, and prone to wild tantrums, and some members of her family considered institutionalizing her. Seeking to improve her condition, in 1886 her parents traveled from their Alabama home to Baltimore, Maryland, to see an oculist who had had some success in dealing with conditions of the eye. After examining Keller, however, he told her parents that he could not restore her sight, but suggested that she could still be educated, referring them to Bell, who despite having achieved worldwide fame, was working with deaf children in Washington, D.C.

Bell’s interest in voice and deafness extended deep into his past. His mother was almost completely deaf, and both his grandfather and father had done extensive scientific research on voice. Bell apprenticed his father from a young age and took an increasingly important role in his work, eventually moving to Boston, where in 1871 he began teaching deaf children to speak using a set of symbols his father had invented, called Visible Speech. In 1877, Bell also married Mabel Hubbard, one of his former pupils whose hearing was destroyed by disease as a child, further deepening his connection to the deaf community.

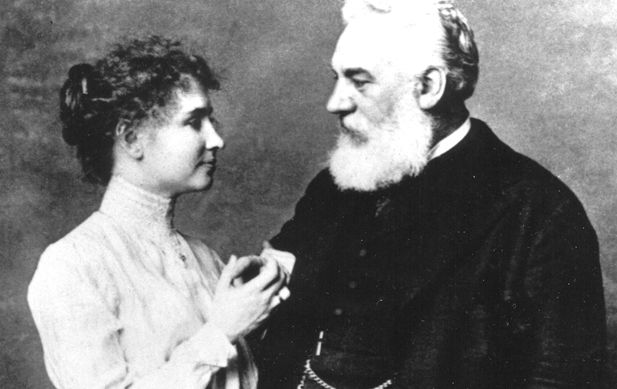

Warmly recalling their initial 1886 meeting, during which Bell made his pocket watch chime so she could feel its vibration, Keller would later write that she felt he understood her and that she “loved him at once.” Bell referred Keller to the Perkins Institution in Boston, and the following March, Anne Sullivan was sent to Keller’s home to begin her education.

READ MORE: Anne Sullivan Found ‘the Fire of a Purpose’ Through Teaching Helen Keller

Keller and Graham brought national attention to the deaf community

After a difficult start, in April 1887 Sullivan broke through to Keller when she traced the word “water” on her hand and then ran cold water over it. Keller retraced the word on Sullivan’s hand, and then eagerly went on to learn 30 more words that day. Writing to Bell shortly thereafter, Sullivan described the breakthrough as a “miracle.” Bell quickly spread word of their accomplishments, publishing an account of the events in various journals, and before long, Keller had become something of a celebrity.

Keller, for her part, was extremely grateful to Bell for broadening her horizons, and Bell to Keller for bringing national attention to deaf education. In the years to come, the two frequently spent time together, developing something of a parent-child relationship along the way.

In 1887, Keller participated in the groundbreaking ceremony for Bell’s Volta Bureau in Washington, D.C., an institution for deaf research that he opened with prize money received in recognition of his invention of the telephone. In 1888, Keller again journeyed north to visit Bell, and this time also met with President Grover Cleveland. (She would go on to meet every subsequent president through Lyndon B. Johnson.)

In 1893, Keller even accompanied Bell to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where they stayed for three weeks, with Bell — who had learned finger spelling to communicate with his mother — acting as Keller’s personal guide and teaching her about modern science and technology.

Bell became further involved in Keller’s education when she expressed a desire to attend a regular college, an idea which he wholly supported. In 1896, Bell coordinated the effort to establish a trust fund for Keller. When Keller began attending Radcliffe College in Boston in 1900, it was this trust fund, as well as further financial support from Bell, that would pay for her schooling. And when Keller graduated from Radcliffe in 1904, she became the first deaf-blind person to do so.

They forged a lasting friendship

Until Bell’s death on August 2, 1922, the bond that he and Keller had established early on would only strengthen. She was a frequent guest in his home, and he remained her constant supporter, both personally and financially. He frequently sent her money to pay for living expenses or vacations, and he even learned to use a braille typewriter so they could correspond more directly. Keller used the braille typewriter to write her first autobiography, The Story of My Life, which she dedicated to him, writing, “To Alexander Graham Bell, who has taught the deaf to speak and enabled the listening ear to hear speech from the Atlantic to the Rockies.”

Thank you for reading this post How Alexander Graham Bell Helped Helen Keller Defy the Odds at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: