You are viewing the article Albert Einstein Once Wrote Marie Curie a Letter Advising Her to Ignore the Critics at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

December 2014 brought a long-awaited moment for Albert Einstein fans when a trove of his personal papers, letters, diaries and postcards became available online via the Digital Einstein Papers project.

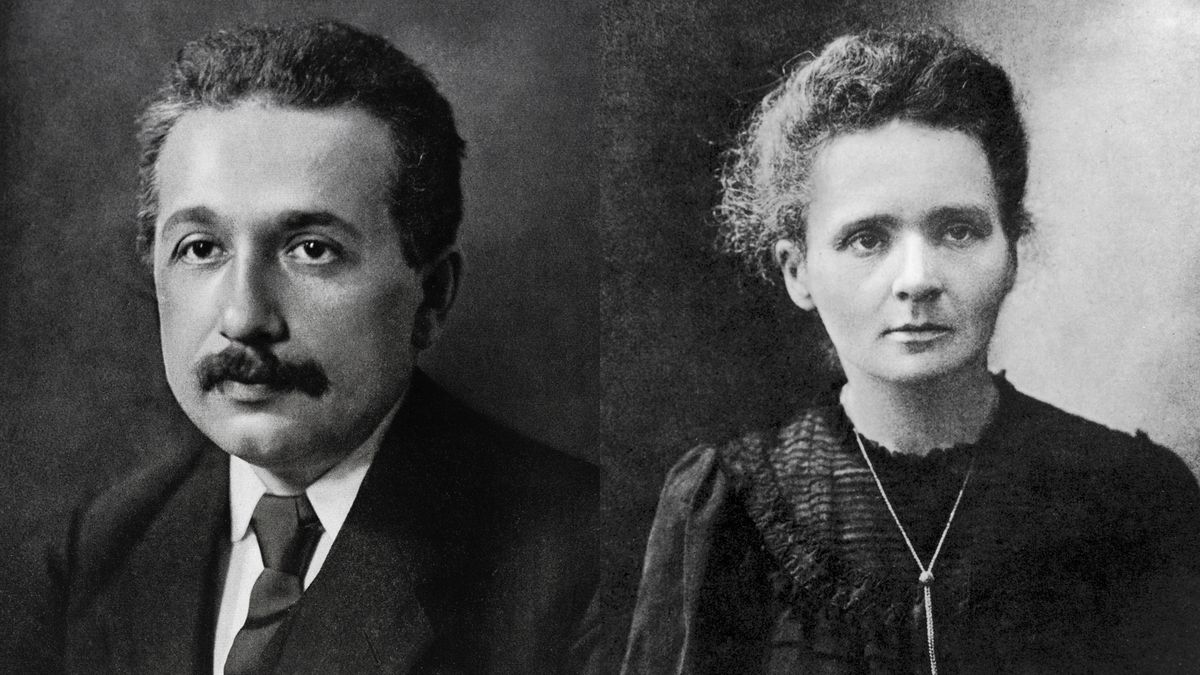

The approximately 5,000 documents offered some insights into his mindset, but the one that stood out to many was his letter to pioneering female physicist Marie Curie that offered a bit of Einsteinian wisdom on how to handle the public’s thirst for details of her private affairs.

Critics pounced during Curie’s bid to join the French Academy of Sciences

The year was 1911 and critics were hating on Curie, the Polish-born wonder woman who shared the 1903 Nobel Prize for Physics with her husband, Pierre, before his untimely death in a horse carriage accident in 1906.

Curie’s bid to become the first woman accepted into the prestigious French Academy of Sciences had been hotly debated in the press, with critics primarily arguing she should either a) concede the seat to an elder and wait her turn, b) leave scientific pursuits to men or c) go back to Poland.

Curie lost a close vote to Édouard Branly, known for his contributions to wireless telegraphy. But the sting of her rejection and the unfavorable media coverage of her candidacy would be a walk in the park compared to the outrage that followed the revelation of her affair with her younger, married associate, Paul Langevin.

READ MORE: What Was Albert Einstein’s IQ?

Her lover’s wife threatened to expose their affair

Langevin had worked closely with the Curies prior to Pierre’s death, and the combination of their shared grief and Langevin’s troubled marriage brought the widow and former disciple together to the point where they were secretly renting an apartment in Paris.

But their affair was not much of a secret to Langevin’s wife, Jeanne, and sometime in early 1911 an investigator had broken into the Paris pied-à-terre and stolen the lovebirds’ letters to one another.

With Jeanne threatening to air their dirty laundry in public, Curie and Langevin remained apart for much of the year, before reuniting in October at the Solvay Conference in Brussels, Belgium, alongside other intellectual luminaries like Einstein.

READ MORE: 5 Fascinating Facts About Albert Einstein

Einstein sent his letter while Curie was being excoriated in the press

Curie returned home in early November to find the news of her liaisons with Langevin splashed on the front page of French tabloids. Her denials and cries of invasion of privacy kept things somewhat in check until another publication blew the lid off the scandal a few weeks later by printing some of the love letters.

The angry editorials about Curie being a homewrecker and a disgrace to France nearly eclipsed the news that she had been named a Nobel Prize winner once again, this time in Chemistry. Now, the Swedish Academy was attempting to back out of an uncomfortable situation by asking her not to attend the award ceremony in December.

Amid one of the most turbulent periods of her life arrived the letter of support from Einstein, who had written to another friend of the “sparkling intelligence” she revealed during the Solvay Conference and offered the following words of encouragement:

Highly esteemed Mrs. Curie,

Do not laugh at me for writing you without having anything sensible to say. But I am so enraged by the base manner in which the public is presently daring to concern itself with you that I absolutely must give vent to this feeling. However, I am convinced that you consistently despise this rabble, whether it obsequiously lavishes respect on you or whether it attempts to satiate its lust for sensationalism! I am impelled to tell you how much I have come to admire your intellect, your drive, and your honesty, and that I consider myself lucky to have made your personal acquaintance in Brussels. Anyone who does not number among these reptiles is certainly happy, now as before, that we have such personages among us as you, and Langevin too, real people with whom one feels privileged to be in contact. If the rabble continues to occupy itself with you, then simply don’t read that hogwash, but rather leave it to the reptile for whom it has been fabricated.

With most amicable regards to you, Langevin, and Perrin, yours very truly,

A. Einstein

P.S. I have determined the statistical law of motion of the diatomic molecule in Planck’s radiation field by means of a comical witticism, naturally under the constraint that the structure’s motion follows the laws of standard mechanics. My hope that this law is valid in reality is very small, though.

Curie became good friends with Einstein

Curie ultimately gathered herself and informed the Swedish Academy that she would attend the award ceremony, which proceeded without incident. And the outrage over the headline-inducing affair inevitably blew over, with Langevin settling things with his wife out of court.

Grateful for Einstein’s support, Curie went on to form a close bond with her fellow scientific celebrity. They vacationed together with their children in the summer of 1913, and she later stood up to anti-German sentiments by lobbying for him to lecture in Paris in 1922.

And while he harbored plenty of scorn for the reptiles who devour unflattering reports of public figures, Einstein had nothing but kind words for his deceased friend during a memorial celebration at New York’s Roerich Museum in 1935.

“I came to admire her human grandeur to an ever-growing degree,” he told the audience. “Her strength, her purity of will, her austerity toward herself, her objectivity, her incorruptible judgment – all these were of a kind seldom found joined in a single individual. … If but a small part of Mme. Curie’s strength of character and devotion were alive in Europe’s intellectuals, Europe would face a brighter future.”

Thank you for reading this post Albert Einstein Once Wrote Marie Curie a Letter Advising Her to Ignore the Critics at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: