You are viewing the article How Mahalia Jackson Sparked Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Long before his most famous August 28, 1963, speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had a dream. He talked about that dream the previous April at a 16th Street Baptist Church meeting in Birmingham, Alabama, of “seeing Negro boys and girls walking to school with little white boys and girls, playing in the parks together and going swimming together.” He continued that dream at a Cabo Hall speech in Detroit that June that he hoped “Negroes will be able to buy a house or rent a house anywhere that their money will carry them and they will be able to get a job.”

So for his biggest audience at the March on Washington, he didn’t think it was worth dwelling on the dream on that hot summer’s day in the nation’s capital. In fact, the dream wasn’t mentioned in the notes that laid on top of the podium and it wasn’t in the plans for that day.

But then, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson — whose life was portrayed in the Lifetime Original Movie Robin Robert Presents: Mahalia — stepped into the picture and changed the entire course of one of the most famous speeches in American history.

Jackson joined King at major civil rights events

Jackson had grown up singing in church from the time she was 4 — and her powerful voice and appeal soon found mainstream success, as she helped pave a path for gospel music outside of churches. By 1947, her song “Move On Up a Little Higher” was a bonafide hit, becoming one of the best-selling gospel songs of all time.

As an international star known as the “Queen of Gospel Music,” who had sold out her Carnegie Hall concerts in New York City, she attended the 1956 National Baptist Convention, where she first met King.

Soon King started asking her to join him at civil rights events around the country over the next years, including the Montgomery bus boycott, the third anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom and Southern Christian Leadership Conference fundraisers.

“She put her career and faith on the line, and both of them prevailed,” Jesse Jackson, who first encountered the singer in the 1960s, told NPR.

King asked Jackson to sing at the March on Washington

As the granddaughter of an enslaved person, Jackson was committed to the civil rights movement, contributing financially as well. “I have hopes that my singing will break down some of the hate and fear that divide the white and Black people in this country,” she had said.

That mission was surely met, as Jesse told NPR, “When there is no gap between what you say and who you are, what you say and what you believe — when you can express that in song, it is all the more powerful.”

When it came time for King to choose a singer to perform at the Washington, D.C. March on Washington for Jobs and Reform, King quickly turned to Jackson. He requested that she sing the Black spiritual song “I Been Buked and I Been Scorned,” which she passionately performed to the more than 200,000 people with lyrics like, “I’m gonna tell my Lord / When I get home / Just how long you’ve been treating me wrong,” setting the tone.

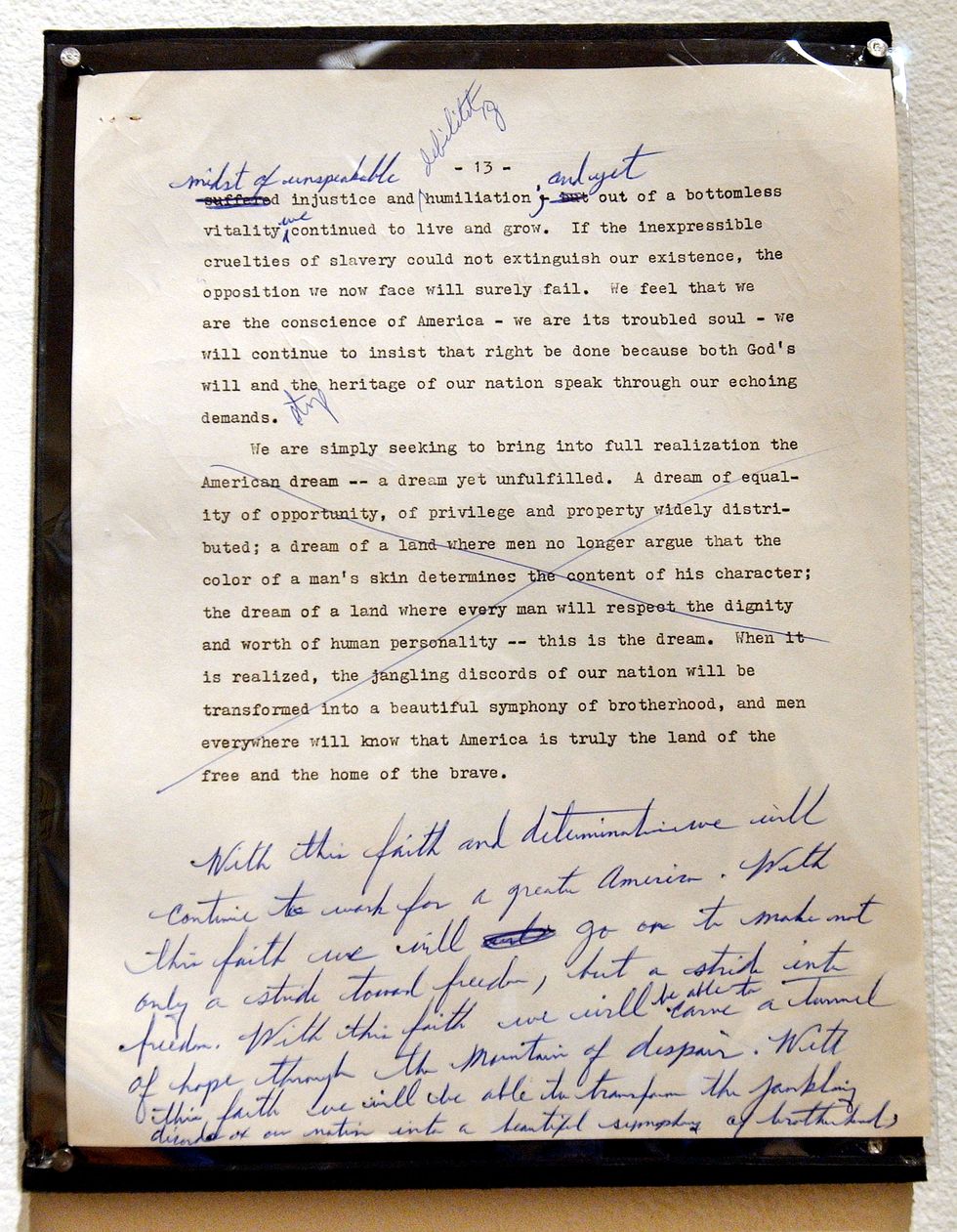

There was no ‘dream’ in the draft of the speech

Understanding how much was at stake with the speech, King had started initial discussions about what he would say at the August march back in the spring of 1963, friend and draft speechwriter Clarence B. Jones wrote in The Washington Post in 2011. Still, it wasn’t until mid-August that the first draft was written up by Jones and advisor Stanley Levison.

Even with all that advance planning, 12 hours before the speech, King still wasn’t sure what he would say, as he sat in the lobby of D.C.’s Willard Hotel with his team. “Everyone, it seemed, had a different take,” Jones wrote, saying that some felt it should have an ideological and political reform take, while others felt it should lean more toward a church sermon.

With so many differing opinions, King asked Jones to draft up an outline. It was then that Jones came up with the opening analogy of “African Americans marching to Washington to redeem a promissory note or a check for justice” and no mention of a “dream.”

When they gathered again, the group started arguing about all the elements that were missing, but King simply took the notes and headed back to his room, leaving them with, “I am now going upstairs to my room to counsel with my Lord.”

A pause in the speech gave Jackson the moment to shout out

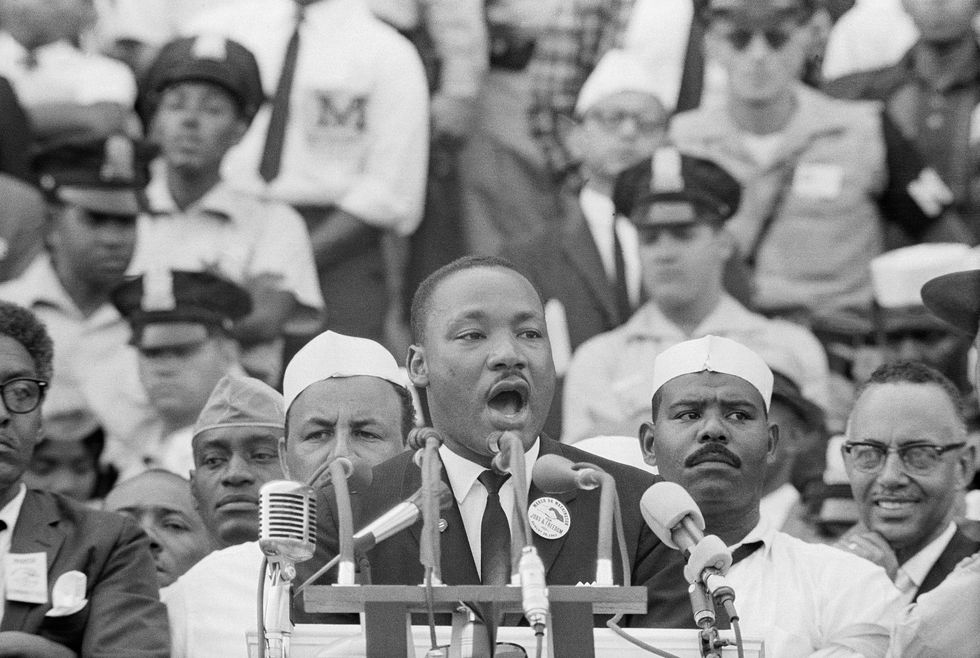

On the day of the now-famous speech, soon after Jackson’s rousing performance, Jones still didn’t know what King was about to say when he stepped up to the podium. He started off with the bad check analogy that Jones had written.

“This was strange, given the way he usually worked over the material Stanley and I provided. When he finished the promissory note analogy, he paused,” Jones continued. “And in that breach, something unexpected, historic and largely unheralded happened.”

That was when Jackson spontaneously shouted, “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin, tell ‘em about the dream!”

At that moment, everything changed. “I see that what he does when he hears her shout that to him,” Jones, who says he was standing 50 feet behind King, told The Washington Post. “He then takes the papers on the lectern and he moves the papers to the left. And then he grabs the lectern on the podium, so I turn to some unknown person next to me and I said, ‘These people don’t know it, but they’re about ready to go to church.’”

Sure enough, King went completely off books. “He was speaking spontaneously and extemporaneously,” Jones said. “His whole body language shifted, became more relaxed, and then as some baptist preachers do, he would take his right foot and started putting it up against his left leg, some preachers do that as they’re talking… and I said, ‘This man is going to preach now.’”

That’s exactly what happened next. Inspired by those words from Jackson, King turned back to the dream. Instead of looking down at his notes, he spoke from his heart — engraving that famous dream into the American history books.

“I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream,” he said. “It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed, ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

The more he spoke about the dream, the more people felt the message. And now, the speech itself is best known as the “I Have a Dream” speech.

King acknowledged Jackson’s role

The moment that Jackson had cried out, as if at a church service, Jones said it was clear that King acknowledged it. “I noticed that when she shouts to him that he looks over to her in real-time momentarily,” Jones told The Wall Street Journal.

Later on, King addressed the impact of the moment. “When I got up to speak, I was already happy,” he wrote to Jackson on January 10, 1962. “I couldn’t help preaching. Millions of people all over this country have said it was my greatest hour. I do not know, but if it was, you, more than any single person helped to make it so.”

In that same letter, he said she was “a blessing to me” as well as “a blessing to Negroes who have learned through [her] not to be ashamed of their heritage.”

As for Jackson, it was in her very nature. “What can we do but help each other?” she once said in an interview. “I don’t go to these meetings [that] do a lot of blab blab blabbing. If you’re going to blab, put your money up there — and do something.” And that she did.

Thank you for reading this post How Mahalia Jackson Sparked Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: