You are viewing the article 12 True Stories Behind Edgar Allan Poe’s Terror Tales at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

No other 19th-century author is as omnipresent in today’s pop culture as Edgar Allan Poe. He has “guest-starred” on the animated series South Park and The Simpsons and been featured as a character in numerous films. His face graces the cover of a Beatles album, he has fought crime alongside Batman in the comic series Batman: Nevermore (2003) and hunted a serial killer in the film The Raven (2012). Every Halloween season, Poe impersonators portray him around the globe; throughout the year, his legions of fans wear his instantly recognizable face on T-shirts, jewelry and tattoos.

While Poe is best remembered today for his tales of psychological terror, he was acclaimed in his own day for his satires, mysteries, science fiction, literary criticism and lyric poetry. Europeans regarded him as America’s first internationally influential author, and Lord Tennyson deemed him as “America’s most original creative genius.”

READ MORE: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” in Popular Culture

Poe’s most chilling tales have lost none of their power in the century and a half since their publication. They continue to speak to each new generation because the stories still seem eerily real. What most readers may not know is that many of these works were inspired by true events as magazine editor Poe kept up with the latest scandals and sensational murder trials and incorporated them into his fiction.

Here are 12 true stories behind Poe’s tales of terror:

“Berenice” (1835)

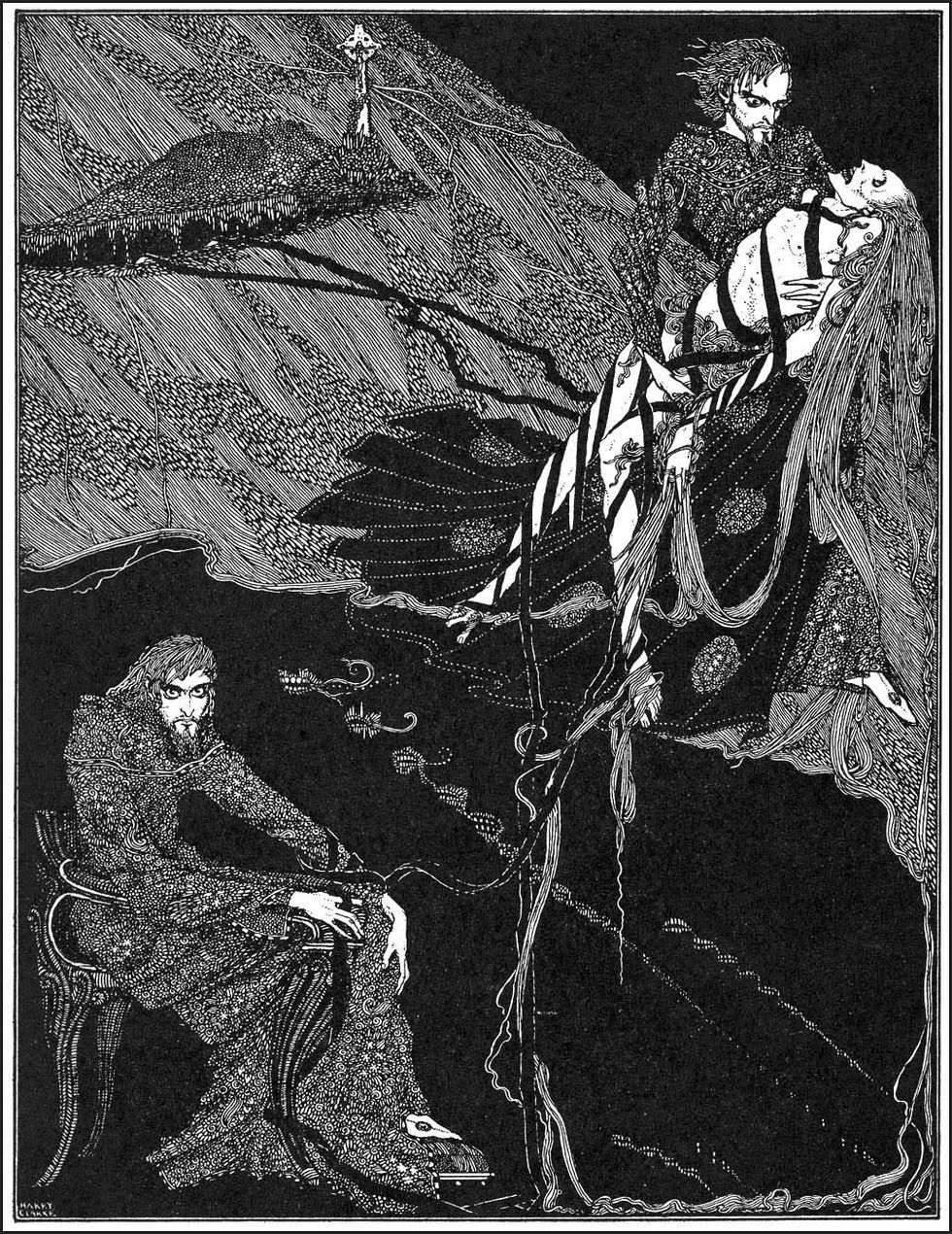

Poe’s first horror story, “Berenice,” is the tale of a man so obsessed with his late wife’s teeth that he digs up her grave to retrieve them. So fixated is he on extracting the teeth that he does not notice the screams of his wife who, it turns out, had been accidentally buried alive.

This grisly subject might have been inspired by actual events. Poe was living in Baltimore when a February 23, 1833 article in the Baltimore Saturday Visiter reported that grave robbers had been caught stealing the teeth of corpses for dentures. Two years later, when he published “Berenice” in the March 1835 issue of the Southern Literary Messenger, Poe told his editor the story “originated in a bet that I could produce nothing effective on a subject so singular, provided I treated it seriously…”

“The Fall of the House of Usher” (1839)

In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the mad Roderick Usher disposes of his twin sister Madeline by entombing her alive in the cellar of their ancestral home. Poe’s inspiration for the insane Usher twins may have been two real-life Usher twins, James Campbell Usher and Agnes Pye Usher. They were the children of Luke Noble Usher, an actor who performed with and was a close friend of Poe’s actress mother, Eliza Poe. Much as in the story, the real Usher twins are believed to have gone insane.

“The Cask of Amontillado” (1846)

In “The Cask of Amontillado,” unfortunate Fortunato pays the ultimate price for insulting Montressor and ends up bricked up alive behind the catacomb wall in this classic revenge story. While Poe was a private stationed at Fort Independence he may have heard the apparently baseless rumor of a soldier entombed alive behind one of the fort’s walls. But history abounds with plenty of other examples of people suffering similar fates.

Poe likely read about it in the August 1844 issue of the Columbian Magazine about some workmen who discovered a skeleton in the wall of the Church of St. Lorenzo. The inspiration for the arrogant victim Fortunato might just be one of Poe’s own enemies, Thomas Dunn English. According to some critics, Poe’s story is a response to English’s novel 1844, or, The Power of the S.F. in which Poe is portrayed as the drunken, licentious author of the poem “The Black Crow.”

After Poe insulted English in print and wrote of the “resemblance between the whole visage of Mr. English and that of the best-looking but most unprincipled of Mr. Barnum’s baboons,” English ridiculed Poe in the novel The Doom of the Drinker as well as in the pages of multiple magazines even after Poe successfully sued one of those journals for libel. The two came to blows in 1846 when, according to Poe, he “wearied and degraded [himself]…in bestowing upon Mr. E. [a] ‘fisticuffing’…and of being dragged from his prostrate and rascally carcass by Professor Thomas Wyatt, who, perhaps with good reason, had his fears for the vagabond’s life…” In his alternate version of the same episode, English boasted he “dealt [Poe] some smart raps on the face” that left him bloody. No matter who won the fight, Poe won the war because “The Cask of Amontillado” has become a classic American short story while English’s The Doom of the Drinker and 1844 are all but forgotten.

“The Pit and the Pendulum” (1842)

In “The Pit and the Pendulum,” an unnamed narrator barely survives a series of tortures devised by the Spanish Inquisition.

When Poe wrote the story in 1842, his readers would likely remember the recent reports of the atrocities committed by the Inquisition, which had been abolished just eight years earlier. Pope Gregory IX established the Inquisition in 1232 to weed out heretics in Catholic Europe. Those accused of heresy could be tortured until they confessed. If they refused to confess, they could be tortured to death or, if found guilty, imprisoned or burned at the stake. In 1478, Spain’s rulers King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella united Spain (which had previously been two kingdoms, Aragon and Castile) by removing all non-Catholics and asked the Pope’s permission to begin the Spanish Inquisition to purify the people of Spain. Because the Spanish Inquisition was run by the king instead of by the church, it battled not only heretics but also the king’s political rivals. The Inquisition also became a source of income for the king because the government confiscated the property of the condemned.

The French had entered Spain in 1808, briefly suppressing the Spanish Inquisition, and several published accounts revealed the horrors they found. Thomas Dick’s 1825 book The Philosophy of Religion reported that “on the entry of the French into Toledo during the late Peninsular War, General Lasalle visited the palace of the Inquisition. The great number of instruments of torture, especially the instruments to stretch the limbs, and the drop-baths, which cause a lingering death, excited horror, even in the minds of soldiers hardened in the field of battle.” Poe was familiar with this work, and it is easy to imagine how the above passage might have inspired his tale — even if Poe did embellish history by inventing a torture chamber with moving walls, a swinging pendulum blade, and a bottomless pit. At the conclusion of the story, it is none other than the aforementioned General Lasalle who comes to the narrator’s rescue.

“The Masque of the Red Death” (1842)

In Poe’s horror story “The Masque of the Red Death,” a plague known as the Red Death is sweeping the land, causing the peasantry to bleed from their pores and suffer an agonizing death. To escape the epidemic, Prince Prospero locks himself and his noble friends in his eccentrically decorate abbey for a masquerade ball. Late in the evening, an uninvited guest arrives, dripping blood and dressed in the habiliments of the grave. When he tries to expel the party crasher, blood gushes from Prospero’s face — revealing that he has been stricken with the Red Death. The other guests seize the intruder only to discover there is nobody inside the costume.

Just 10 years before he wrote this story, Poe survived the Cholera Epidemic of 1832. This pandemic began in India and spread from Europe to the United States. Unlike the Red Death, however, cholera’s symptoms included severe diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration followed by death. Terrified citizens fled the cities to escape what many considered an urban disease disproportionately affecting the urban poor, the sinful, and the intemperate. Poe was living in Baltimore, a city of 80,625 where cholera claimed 853 of the city’s residents between August and November 1832. Back in Poe’s hometown of Richmond, Virginia, cholera claimed one of his best friends, Ebenezer Burling.

In the midst of all this fear and suffering, a group of two thousand Parisians decided to celebrate what seemed to be the end of the world by throwing a masquerade ball at the Théatre des Varietés. At the stroke of midnight, one of the guests arrived dressed as the personification of Cholera with skeletal armor and bloodshot eyes. An account of the party appeared in the June 2, 1832 issue of the New-York Mirror where Poe probably saw it.

“The Mystery of Marie Roget” (1842)

The second of Poe’s detective stories to feature the amateur sleuth C. Auguste Dupin, “The Mystery of Marie Roget” boasts that it provides the solution to a real-life mystery — the unsolved murder of Mary Cecelia Rogers. Nicknamed “The Beautiful Cigar Girl,” Rogers worked behind the counter of Anderson’s Cigar Emporium in New York City. Two days after she disappeared in 1841, her body was found floating in the Hudson River off the coast of Hoboken. Although there was no shortage of suspects, the police were unable to identify her murderer. Newspapers fueled the public’s outrage and fascination by reporting all the latest details in the investigation.

William Snowden, owner of The Lady’s Companion, was the single largest supporter of the Commission for Safety, which was raising funds for information that would lead to the killer’s capture. Poe answered the challenge by selling Snowden “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” which Poe promised not only “indicated the assassin in a manner which will give renewed impetus to investigation” but also demonstrated a method of investigation that could be used by real police departments in future cases. As press coverage of the case revealed new clues, Poe added these details to his story. When he included the work in a collection of his tales a couple of years later, he changed the story again to stay in keeping with the latest theories circulating in the papers.

“The Oblong Box” (1844)

In “The Oblong Box,” Mr. Wyatt travels by ship from Charleston to New York with his sisters, a woman claiming to be his wife, and a large oblong box. He encounters an old college friend who is perplexed about the contents of this mysterious object. When the ship sinks in a storm, Wyatt follows his box into the water rather than abandon it for the safety of the lifeboat. Only later does Wyatt’s friend discover that the woman pretending to be Wyatt’s wife was his servant and that Wyatt’s actual wife died before the journey and was being secretly transported in the box of preservative salt because the ship’s crew was superstitious about having a corpse on board.

Three years before Poe published this gruesome tale, newspapers around the country covered the sensational case of John C. Colt, brother of the future revolver manufacturer Samuel Colt. In 1841, John murdered the printer Samuel Adams over an unpaid bill, stuffed his body into a box of salt, and shipped it to New Orleans. When Adams’s friends noticed his absence and alerted the police, it was only a matter of time before they found the box aboard a ship. The crew apparently mistook the stench of the decomposing cadaver for rat repellent.

“William Wilson” (1839)

At an exclusive British boarding school, a boy named William Wilson meets another boy who, by coincidence, looks exactly like him, shares the same birthday, and is also named William Wilson. Let’s call him William Wilson 2. William Wilson 1 is a horrible boy who grows into a despicable young man, but, whenever he is about to commit another crime, William Wilson 2 shows up to get him in trouble. The story follows William Wilson 1 from Dr. Bransby’s boarding school to Eton and then to Oxford, “the most dissolute university in Europe,” where he proceeds to swindle his classmates by cheating at cards.

In writing the story, Poe used real locations, including the boarding school he attended as a boy in England. Just as in the tale, the real school was administered by a Reverend Bransby. When asked how he felt about his unflattering portrayal in his former student’s story, the real Bransby shunned the subject and told William Elijah Hunter that Poe “would have been a very good boy if he had not been spoilt by his parents.”

The location that inspired Eton and Oxford was Poe’s alma mater, the University of Virginia. Fighting, drinking and gambling were rampant at the University in Poe’s day. In fact, one of his classmates was expelled for biting another student, and another was expelled for horsewhipping someone for cheating at cards. Poe lost heavily at cards and left the University with over $2,000 in gambling debt after just one term. In a letter to the anthologist Rufus Griswold, Poe wrote that, while at the university, he “led a very dissipated life — the college at that period being shamefully dissolute.”

“Some Words with a Mummy” (1845)

Americans in Poe’s time were fascinated with ancient Egypt. His age saw the discovery of new Egyptian antiquities, the construction of Egyptian Revival buildings, and mummy unwrapping parties. Poe’s story “Some Words with a Mummy” recreates a mummy unwrapping party at which some heavy-drinking scientists decide to shock their unwrapped mummy back to life using a Voltaic pile, an early kind of electric battery.

Poe himself was no stranger to mummies. When he was 14, he undoubtedly saw a mummy on display in the Virginia State Capitol, which was only a couple blocks from Poe’s home.

“The Premature Burial” (1844)

“The Premature Burial” is only one of Poe’s five tales to deal with the subject of being buried alive. In this story, a man who suffers from seizures is terrified that he will be mistaken for dead and accidentally interred while in this state. This was not a terribly unusual fear during Poe’s time. When most people died at home and were quickly buried without being embalmed, newspaper stories occasionally reported cases of people hearing the screams of the wrongfully buried and rushing to their rescue. The danger was common enough that concerned citizens could buy their loved ones “safety coffins” in which the accidentally buried who awoke in his or her coffin could ring a bell that would (hopefully) be heard above ground by someone who could come to their aid.

In 1843, Christian Henry Eisenbrandt patented a “life-preserving coffin” which would spring open with the slightest movement of the occupant. Poe’s stories on the subject did not help things, and the phobia persisted throughout the 19th century. The Society for the Prevention of People Being Buried Alive was founded in 1896 for obvious reasons. Among other ideas, the Society proposed a law that would prevent the burial of people until they started to “smell dead.”

Politian (1836)

Politian is Poe’s only attempt at writing a play. He published the unfinished drama in the Southern Literary Messenger and later reprinted it in an anthology of his poetry. Even though Poe never completed the work, what survives involves a jealous woman scheming to convince one man to murder another for her.

The play was based on the “Kentucky Tragedy” of 1825 in which a politician named Colonel Solomon P. Sharp seduced a girl named Anna Cook. Although she had a child with him out of wedlock, Sharp refused to marry Cook. To avenge this rejection, she then convinced another suitor, Jereboam O. Beauchamp, to challenge Sharp to a duel, but Sharp declined. After Beauchamp and Cook married, the former went to Sharp’s house in the middle of the night and stabbed him to death. The case made national headlines, and Poe probably read about it in a book he reviewed as a literary critic for The Southern Literary Messenger.

“The Tell-Tale Heart” (1843)

An unnamed narrator is driven to murder by the sight of an old man’s hideous eye. Although he has supersonic hearing, the narrator repeatedly assures us he is not mad and, as evidence, tells us how calmly and methodically he can tell the tale — until he starts hearing the dead victim’s heart beating from its hiding place under the floorboards.

Different real-life murders have been cited as the inspiration for Poe’s tale. Among them is the 1830 murder of Joseph White of Salem, Massachusetts. The special prosecutor on the case, Daniel Webster, published his Argument on the Trial as a pamphlet. In the text, he writes that the murderer’s guilt will eventually reveal itself and that “the secret which the murderer possesses soon comes to possess him…it overcomes him…He feels it beating at his heart, rising to his throat, and demanding disclosure. He thinks the whole world sees it in his face, reads it in his eyes, and almost hears its workings in the very silence of his thoughts. It has become his master.”

Another likely source is the 1840 trail of James Wood for the murder of his daughter. Wood pled that he was not guilty, by reason of insanity, so the question put to the jury was whether or not Wood was mad. The reporter covering the trial for Alexander’s Weekly Messenger states that, although Wood’s calm demeanor might lead some to believe him a “premeditated and cool-blooded assassination” rather than a madman, he believes this calmness is merely the “cunning of the maniac — a cunning which baffles that of the wisest man of sound mind — the amazing self-possession with which at times, he assumes the demeanor, and preserves the appearance, of perfect sanity.” The jury in the case ruled in Wood’s favor and sent him to an asylum. The Messenger reporter was none other than Poe.

Thank you for reading this post 12 True Stories Behind Edgar Allan Poe’s Terror Tales at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: