You are viewing the article How the Kennedy-Nixon Debate Changed American Politics at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

The 1960 presidential race was one of the closest in United States history. It was a battle between new and old, with the Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy, a handsome young optimist, squaring off against Vice President Richard Nixon, who was only slightly older but was known for having something of a dour demeanor. The election would chart the course of America’s future, and the first debate between the two candidates would have an outsized impact on the direction that would be chosen.

Kennedy was generally seen as winning the debate and he ultimately squeaked through with an election victory. But the real lasting winner of that first debate was the medium through which most people experienced it: television.

The presidential debate is a relatively new phenomenon

Today, presidential debates feel like an ingrained tradition, essential to any race for the White House. In reality, they’re actually relatively recent additions to the American democratic process. Before the 20th century, candidates didn’t really do much public campaigning for the presidency — posters, slogans and pamphlets became popular by the middle of the 19th century, but the lack of mass communication technology limited the usefulness of in-person events. The advent of radio kicked off the broadcast media political campaign in the 1920s and politicians became masters of the medium.

In 1940, Republican Wendell Wilkie challenged President Franklin D. Roosevelt to a radio debate, but despite having an elite command of the airwaves through his Fireside Chats, Roosevelt declined.

In the early-to-mid 1950s, the number of American households with at least one television set skyrocketed, and by the 1956 presidential election, they were in just about two thirds of all homes. That year, a student at the University of Maryland named Fred Kahn began a campaign to engage the two major presidential candidates, President Dwight Eisenhower and Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson, to debate the issues of the day on national TV. Kahn was a Holocaust survivor and thought it was important for Americans to be engaged with the political process.

“It’s democracy. I had been stateless. I became a citizen. Therefore, I wanted to be a good citizen,” he told the Washington Post in 2012.

The public campaign fell short in ‘56, but it planted the seed for a debate that came to fruition in 1960.

Kennedy and Nixon perpared differently for the debate

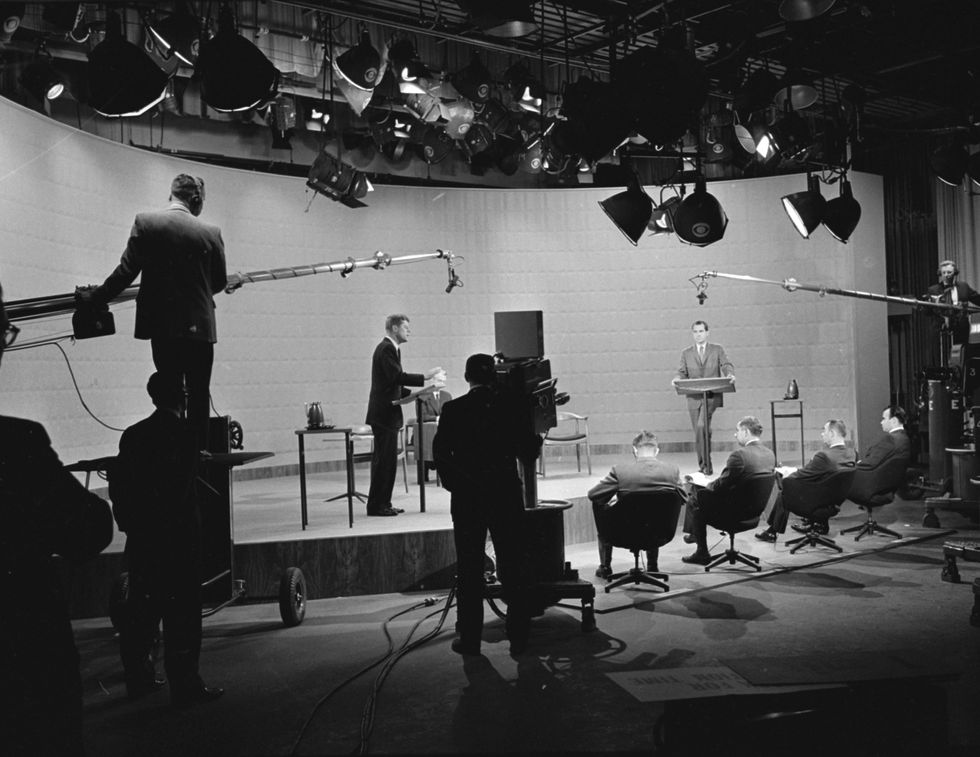

The first-ever televised presidential debate took place on September 26, 1960, in Chicago and was broadcast on CBS to 66.4 million TVs across the country. The two very different candidates were neck-and-neck in the polls at the time, but only one of them seemed to understand the potential power of the event in which they were about to participate.

The difference in their preparation in the weeks leading up to the debate was stark.

Late that summer, Nixon injured his knee during a visit to Greensboro, North Carolina. He didn’t feel much pain at first, but the bruise wound up getting infected and sent him to the hospital for several weeks. He lost 20 pounds during his forced sidelining and when he hit the road again, he was weak, pale and exhausted-looking.

Sensing that he was falling behind, Nixon doubled down on intense campaigning, traveling the country and putting his weakened body through more physical strain. He caught the flu in St. Louis and wound up hurting his knee again, and yet he insisted on continuing his punishing campaign, meeting voters and appearing at events up through the afternoon of the debate.

Kennedy, on the other hand, knew the power of television — he was running as much on his telegenic image and enviable, seemingly picture-perfect family. Instead of draining himself on the campaign trail, Kennedy holed up in a hotel for the entire weekend before the telecast, preparing for the questions from a panel of four journalists and the judgment of tens of millions of Americans at home.

They were largely similar in their policy goals and civil in their discourse. Kennedy proposed a healthcare system that looks similar to what would become Medicare, while Nixon touted his experience in the executive branch. They were from all accounts reasonably matched in their mastery of the issues — Nixon even said they shared many of the same aims in his closing remarks.

But for however similar they sounded, their presentation was quite different.

The Kennedy-Nixon debate illustrated the power of TV

Neither man accepted help from CBS’s makeup professional, but Kennedy supposedly brought his own team for touch-ups on a face that was already glowing from time out in the sun. Nixon, meanwhile, looked drained, had a terrible five o’clock shadow, and was sweating profusely. His suit blended in with the dried paint on the set wall, making Nixon a literal shadow of a man on TV.

Viewers at home took notice, as did the people in the television studio. Howard K. Smith, who hosted the event, said the difference between the two men’s presentation was stark.

“I gave Nixon eighteen-and-a-half points to Kennedy’s eighteen. So I gave it to Nixon. But I couldn’t see them,” he said in an interview years later. “They were ahead of me facing the camera that way. So I was listening to it on radio as it were. Later when I went back and saw it replayed, I could see that Kennedy swept it. He just looked so enchanting.”

Not everyone was sold — Edward R. Murrow quipped after the debate that “after last night’s debate, the reputation of Messieurs Lincoln and Douglas is secure,” a reference to the famed Lincoln-Douglas Senate debates in the 1850s.

Kennedy wound up winning the election, and years later, Nixon would look back on the debates as the events that sunk his candidacy in 1960. He probably knew it even then — he wrote in his memoirs that “after the program ended, callers, including my mother, wanted to know if anything was wrong.”

Lyndon B. Johnson, president for just over a year when he ran for re-election in 1964, avoided any televised debates. Later, when Nixon ran for the presidency again in 1968, he outright refused to debate Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey, then declined a debate in 1972 against Democrat George McGovern. The debates would return for good in 1976, when Gerald Ford — who took over for Nixon after his resignation — revived them in his failed campaign against Jimmy Carter.

After that, television became the dominant medium for presidential politics, with Ted Turner’s creation of cable news network CNN in 1980 heralding the dawn of the era in which we now live.

Thank you for reading this post How the Kennedy-Nixon Debate Changed American Politics at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: