You are viewing the article George Takei and Pat Morita’s Harrowing Childhood Experiences in Japanese American Internment Camps at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

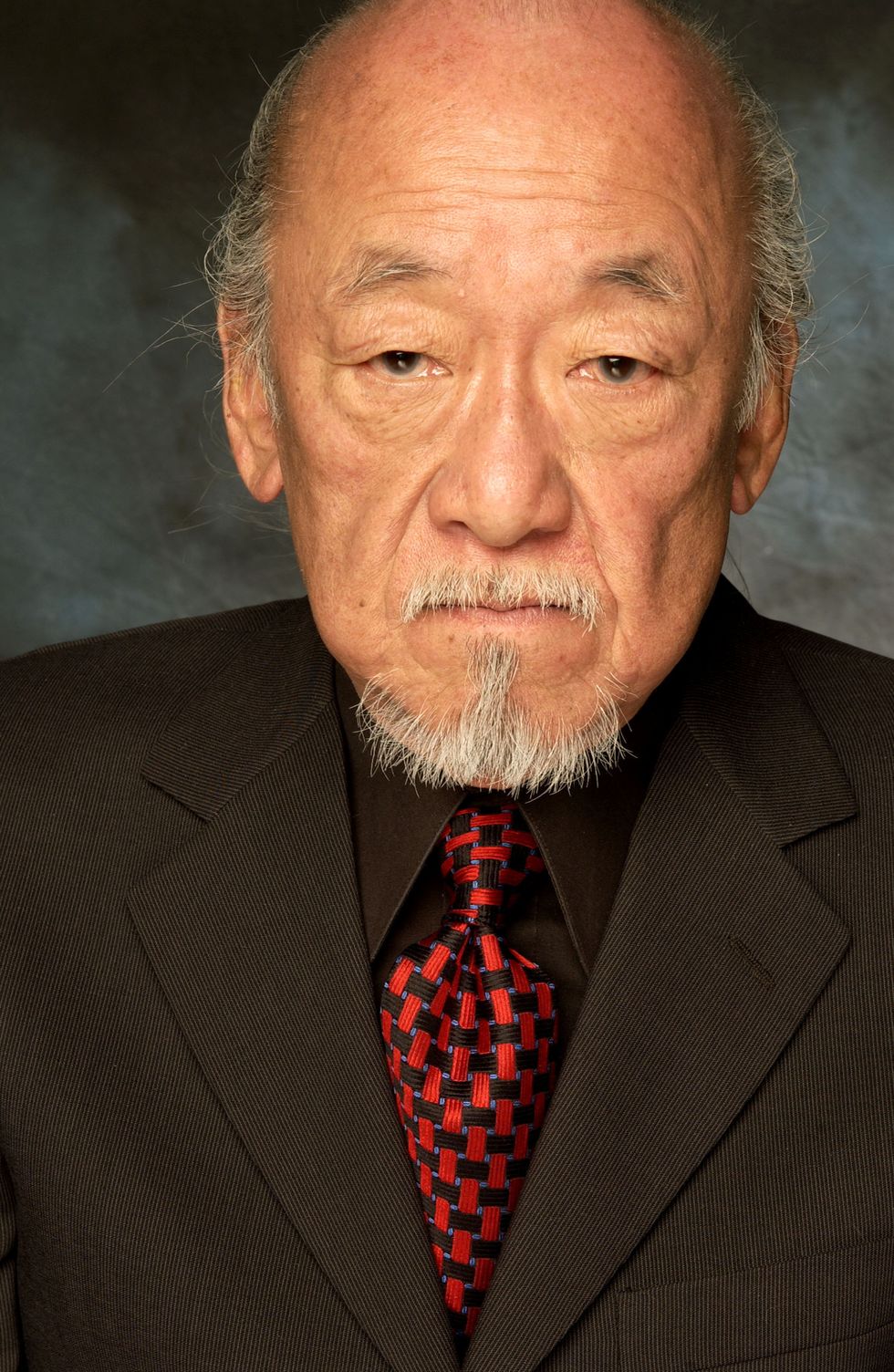

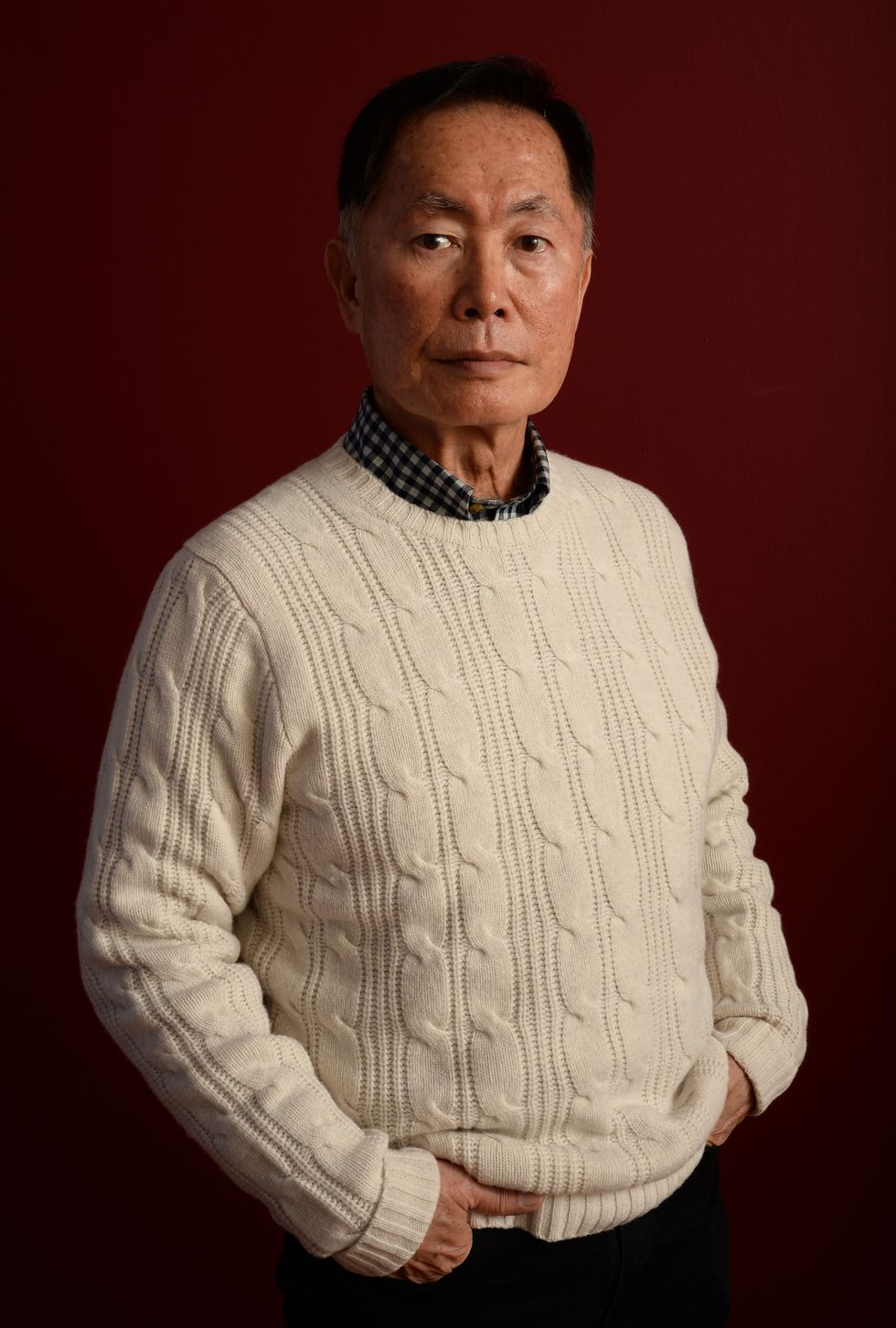

At a time when Asian Americans were hardly seen on screen, Pat Morita and George Takei broke new ground — seizing roles where they were able to play against stereotypes in the 1960s and ’70s.

Morita portrayed Matsuo “Arnold” Takahashi on the sitcom Happy Days from 1975 to 1983 before his Academy Award-nominated role as Mr. Miyagi in The Karate Kid film franchise — and even starred in the first Asian American network TV sitcom, Mr. T and Tina in 1976. Takei rose to recognition as Lieutenant Hikaru Sulu in the Star Trek series from 1966 to 1969 and through six of the franchise’s films.

Pioneering uncharted territory together, Takei had the utmost respect for Morita, who was five years his senior. “He was extraordinary in that Pat was of a generation of Asian Americans that rarely ventured into show business,” Takei wrote upon Morita’s death from kidney failure in 2005. “It was an insecure and inhospitable arena for Asian performers. Yet, with his passion and his gift of humor, he boldly ventured forth into that unpromising world.”

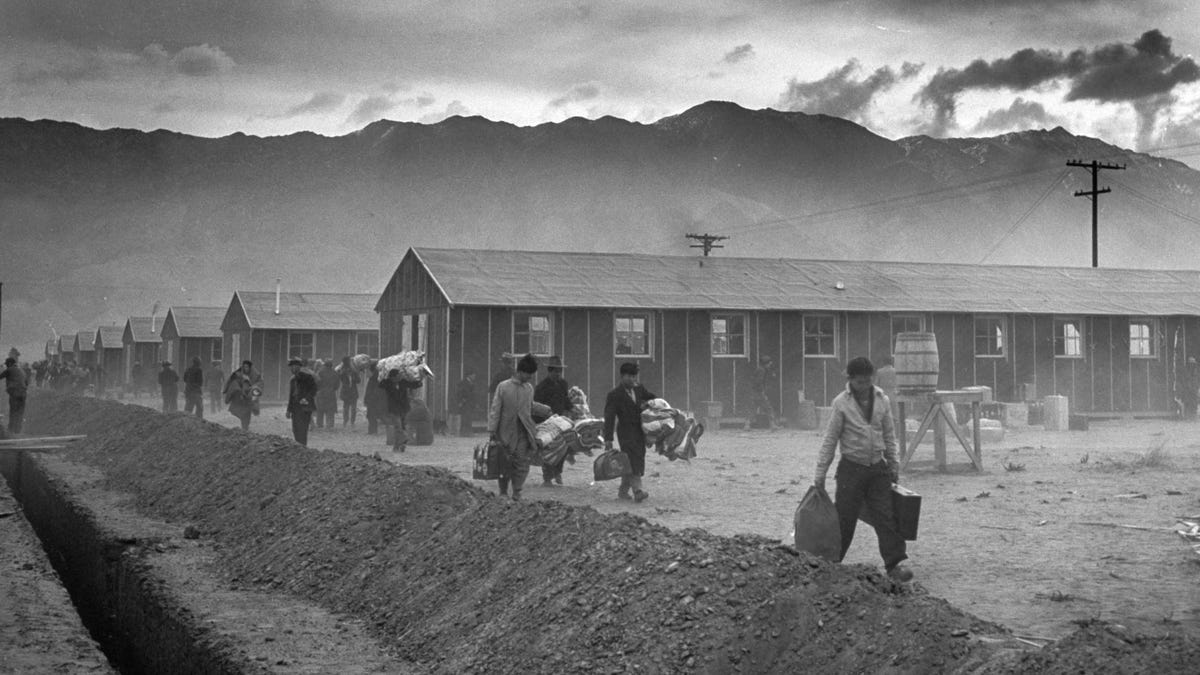

Beyond Hollywood’s ethnic barriers, the friends were also bonded through a shared horrific childhood experience — one of the darkest chapters of American history — as both were forced to live at Japanese American internment camps in the United States during their early years.

Morita said the camps were ‘America’s version of concentration camps’

From the time he was a toddler, Morita faced some of life’s biggest challenges. Born Noriyuki Morta on July 28, 1932, he was confined to a body cast because of spinal tuberculosis from the time he was 2 years old. Learning to walk at age 9, he spent nine years in a “charitable infirmary for poor, immigrant children at San Francisco’s Shriners Hospital,” his daughter Aly Morita wrote in the Asian American publication Hyphen.

In August 1943, he was finally able to leave the hospital but was sent directly to join his parents, fruit pickers who had immigrated to the United States from Japan between 1907 and 1912, at a prison camp during World War II.

“The war was on, and so I was escorted from the hospital by an FBI guy to join my parents at an internment camp in the middle of Arizona,” Morita said in an interview with the Television Academy. “What do kids know about wars? I was happy to be walking, they said this kid would never walk — and I felt like I was some kind of big deal because an FBI guy… was escorting me.”

Taken to the site by the Gila River, Morita was overcome by the new environment. “I cried for four days I was so homesick for the doctors and nurses,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1986. He was there for a year and a half with his family before they were forcibly moved to another internment camp near the border of California and Oregon called Tule Lake.

“Uncle Sam and we Americans like to use euphemistic words or invent words if we think certain other words are too harsh,” Morita told the Television Academy. “So they called them ‘relocation centers,’ but they were America’s version of concentration camps.”

Takei’s family of five was forced to sleep in a horse stall

Born in Los Angeles on April 20, 1937, Takei was only four years old during Pearl Harbor — and had just turned 5 when he remembers the harrowing knock on the door.

“We saw two soldiers, marching up our driveway, carrying rifles with shiny bayonets on them,” he recalled on Late Night with Seth Meyers. “They stomped up the porch and with their fists began pounding on the door. The way I remember it, the whole house seemed to tremble. My father came out and answered the door and, literally at gunpoint, we were ordered out of our house.”

Along with his younger brother, baby sister and parents, they were first sent to the Santa Anita Race Track while the camps were being built.

“We were herded over with other Japanese American families to the stable area and assigned a horse stall for us to sleep in — from my two-bedroom home with a front yard and backyard on Garnet street in L.A., to a horse stall,” Takei explained. “For my parents, it was a degrading, humiliating, painful experience to take their three children into that smelly horse stall, still pungent. I still remember that smell.”

Through his childhood lens, it felt like an adventure. “We get to sleep where the horses slept! Fun!” he told NPR.

Of course, imprisoned life behind barbed wires — sometimes three layers thick — was anything but fun, looking back with an adult lens. His family was forced onto a train across the country to Rohwer, Arkansas, where 16,000 of the estimated 110,000 to 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent were locked up. After two years there, they were on the move again.

“I was 7 years old when we were transferred to another camp for ‘disloyals,’” he wrote in The New York Times in 2017. “My mother and father’s only crime was refusing, out of principle, to sign a loyalty pledge promulgated by the government.”

Coincidentally, he ended up at Tule Lake, which was the same prison camp that Morita’s family moved to. While it’s unknown if they crossed paths, their roads out of imprisonment did eventually converge.

Life after the internment camps was a big adjustment for both families

Returning home was a harsh slap in the face for both families. When Morita’s family was freed in October 1945, they had to start life from the bottom again, living out knapsacks and working back in the crop fields. Eventually, they saved enough to open a Chinese restaurant in Sacramento, California. “A Japanese family running a Chinese restaurant in a Black neighborhood with a clientele of Blacks, Filipinos and everybody else who didn’t fit in any of the other neighborhoods,” Morita explained to the Los Angeles Times.

Against all odds, the restaurant prospered — and after stints as a data processor at the DMV and Aerojet-General, Morita decided to quit and pursue his true passion of acting.

Meanwhile, Takei’s family’s reintroduction to freedom was heartbreaking as well. While they used their one-way ticket to go back to Los Angeles, according to TheNew York Times, authorities had taken their home and his parents’ thriving dry cleaning business.

“Los Angeles was not a welcoming place,” Takei recalled in a 2014 TED Talk. “We were penniless. Everything had been taken from us and the hostility was intense. Our first home was on Skid Row in the lowest part of our city, living with derelicts, drunkards and crazy people. …My baby sister said, ‘Mama. Let’s go back home,’ because behind barbed wires was for us home.”

But the family’s grit and determination won out. They earned enough to get a three-bedroom home. And during Takei’s teen years, he started wondering about his experience.

“I read civics books that told me about the ideals of American democracy — all men are created equal,” he said in the TED Talk. “We have an alienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. And I couldn’t quite make that fit with what I knew to be my childhood imprisonment.”

He dove in history books and conversations with his father to better understand the journey he had been through — unknowingly prepping for the life he was about to carve out for himself.

Takei is committed to ensuring America doesn’t forget the discriminatory internment camps

While Takei no longer has his friend Morita, who related to his unfair childhood imprisonment, he is committed to telling the story of the American internment camps that those of Japanese ancestry were forced to live in.

“Our oft-repeated plea is simple: We must understand and honor the past in order to learn from and not repeat it,“ Takei wrote in TheNew York Times.

He’s continued telling his experience in as many art forms as possible: His 2015 autobiography To the Stars, the 2012 musical inspired by his life Allegiance, a New Frontiers exhibit at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles and a 2019 graphic novel They Called Us Enemy. He also has revisited the time in 2019 on the second season of the show The Terror: Infamy, where a 6.5-acre replica of the camp where he was imprisoned was built.

Takei has also set out to educate fellow Americans on how to talk about the time, noting that it’s an error to call sites “Japanese internment camps.”

“According to the grammar, [that] would lead you to think that they were run by the Japanese government,” he said on Late Night with Seth Meyers. “They were American concentration camps for Americans of Japanese ancestry. We were in Japanese American internment camps. But the press always, for the last 75 years, have been referring to those camps as ‘Japanese internment camps’ and it drove me up the wall every time I hear it.”

The more he speaks out, the more he hopes the United States will draw from the experience and move forward. “I wish that those, like me, who lived through this nightmare before didn’t have to sound the alarm again,” Takei wrote in Foreign Policy in 2018. “But as my father once told me, America is a great nation but also a fallible one — as prone to great mistakes as are the people who inhabit it. As a survivor of internment camps, I have made it my lifelong mission to work against them being built ever again within our borders.”

Thank you for reading this post George Takei and Pat Morita’s Harrowing Childhood Experiences in Japanese American Internment Camps at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: