You are viewing the article How Louisa May Alcott’s Real-Life Family Inspired ‘Little Women’ at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Louisa May Alcott had come to Europe to rest. But even in the Swiss Alps, the author couldn’t escape the thing that had exhausted her in the first place: her fans.

Her latest book, Little Women, was a runaway bestseller — and the constant barrage of fan mail, the visits and the demands on her time had wrecked her already delicate health. “Don’t send me any more letters from so cracked girls,” she begged her mother in a letter from Switzerland in 1870. “The rampant infants must wait.”

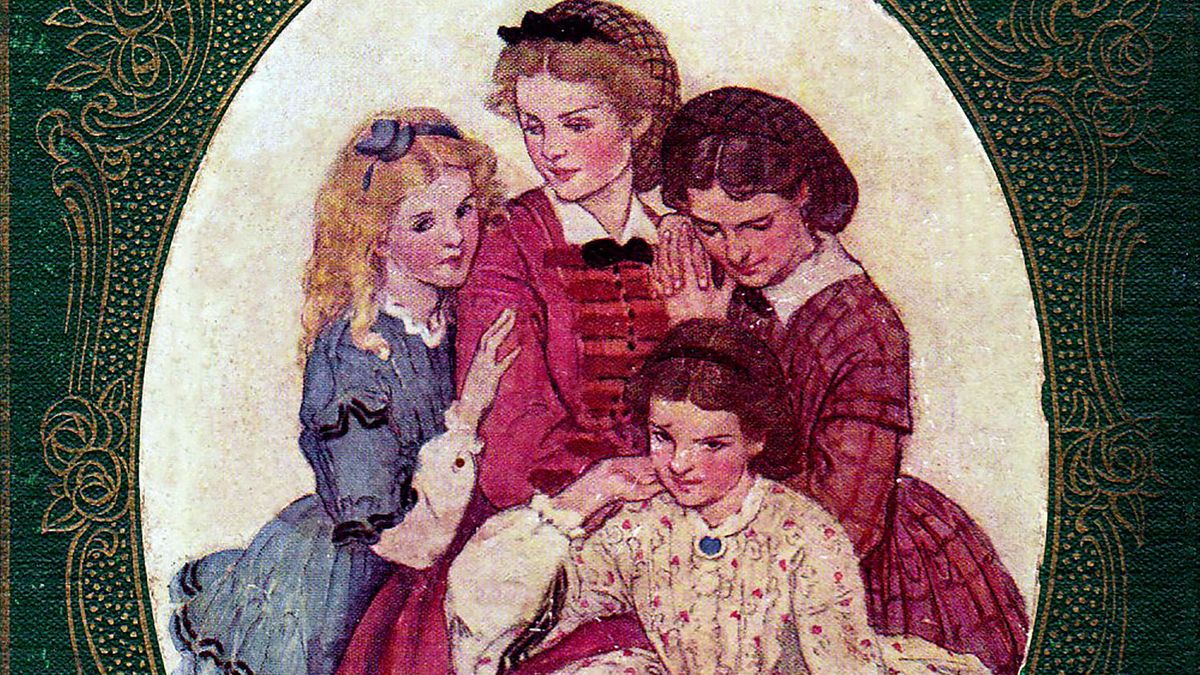

The “infants” were Louisa’s fans, and ever since the publication of Little Women, they had bombarded her with letters asking for a sequel and demanding to know how much of the book was autobiographical — a question readers still pose today. Louisa had captured the world’s imagination with her tale of the brave, beloved March family, and Little Women — a book about the Civil War–era lives of Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy March, four sisters who struggle with life, love and friendship — has never been out of print. But Louisa’s real-life family, upon whom the book was partly based, was infinitely more complicated — and even more interesting.

Louisa’s father was a transcendentalist

Born in Pennsylvania in 1832, Louisa was one of four sisters, the daughters of Amos Bronson Alcott and Abigail “Abba” Alcott. Bronson, a self-educated Romantic, left his Connecticut home as a teenager to become a Yankee peddler, a type of traveling salesman. Life on the road suited the idealistic, optimistic Bronson, but he was a bad salesman and soon found himself in debt. This began a pattern of financial mismanagement and poverty that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Even though Bronson couldn’t handle money, he was passionate and idealistic — high-minded ideals attracted the young Abba. Born into relative wealth and social prestige as the daughter of a prominent New England family, Abba was drawn to Bronson’s love of education and social justice. The couple married in 1830.

Where Bronson was absent-minded, Abba was practical. When her husband’s schools failed because of his controversial, student-focused teaching methods, she lent him moral support. When he infuriated parents by admitting an African American student to his Boston school, she stood by him. And when he immersed himself in Transcendentalism — a new progressive philosophical movement that emphasized self-reliance, imagination and creativity — she went right along with him.

He began a utopian commune which served as inspiration one of Louisa’s satires

Bronson was always in search of ways to put his ideals into action, and in 1843 he picked up his family and began a utopian commune called Fruitlands in Harvard, Massachusetts. It was an unmitigated disaster. Though it was supposed to be a communal farm, Bronson knew nothing about farming and refused to use animals to work the land. The family kept to a vegetarian diet and eschewed all products derived from enslaved people labor. The land was hard to farm and the family nearly starved. Eventually, the experiment strained Abba and Bronson’s marriage nearly to a breaking point. Fruitlands failed in 1844 after just eight months.

Louisa would later write a satirical account of her family’s time at Fruitlands, called Transcendental Wild Oats. In it, she represents her father as a doomed dreamer whose philosophies are unsuited to the harsh world. “The world was not ready for Utopia yet,” she wrote, “and those who attempted to found it only got laughed at for her pains.” Privately, though, Louisa was much more negative about Bronson’s inability to support his family.

Louisa had three sisters who mirrored the March sisters

Even after moving back to Concord, Massachusetts, the family struggled with money. Bronson, consumed with causes linked to Transcendentalism and abolitionism, rarely worked, so Abba had to pick up the slack. She became one of America’s first professional social workers, and her daughters, Anna, Louisa, Elizabeth and Abigail May, worked as governesses, domestic servants and teachers to help support the family.

Oldest sister Anna, on whom domestic, marriage-minded Meg March of Little Women was based, was a talented actor, but felt her only option was to marry to escape her family’s poverty. “I have a foolish wish to be something great and I shall probably spend my life in a kitchen and die in the poor-house,” she wrote in her diaries.

Little is known about the inner life of Elizabeth, the third Alcott daughter, who was called “Lizzie” by her family. Her death at age 22 of scarlet fever devastated the Alcotts, and the angelic character of Beth March in Little Women, who, like Lizzie, contracts a fatal illness after helping a poor family, is Louisa’s tribute to her sister.

Abigail, better known as May, was the youngest Alcott sister, and she had big ambitions. With the financial assistance of Louisa, who had found success as a writer of short stories, poems and essays, May trained as an artist in Boston and Europe, gaining recognition as a painter and rubbing shoulders with figures like the Impressionist painter Mary Cassatt. In 1877, one of her paintings was displayed in the Paris Salon, and, as one of the few professional women artists of her age, she fought discrimination in her profession and struggled to help other poor women pursue art. Amy March, a self-centered artist who finds love with the family’s next-door neighbor in the novel, is based on May.

Though Louisa was just as independent and talented as Jo March, her literary counterpart, her life was marked by struggle and sorrow. During her bout as a Civil War nurse, she was treated with mercury for typhoid. Modern doctors believe she likely suffered from an autoimmune disorder such as lupus, based on photographs that show a rash on her face. Regardless of any health issues, Louisa worked herself to exhaustion trying to provide for her family.

Louisa was skeptical about ‘Little Women’

In 1868, Louisa’s publisher asked her to write a book for girls. At first, she protested, but her need for money drove her to comply. In a matter of weeks, she dashed off the first volume of Little Women. “I plod away although I don’t enjoy this sort of thing,” she wrote in her journal at the time. “Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters, but our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting, though I doubt it.”

Louisa’s skepticism was unfounded: Little Women was a smash hit. Soon, readers demanded a sequel. Louisa continued the story of Jo and her sisters with a second volume of Little Women that followed the girls into adulthood and marriage. She went on to publish multiple novels for girls, but felt hemmed in by her public image as the beloved author of children’s stories. Her adult fiction, which explored quandaries of love, feminism and philosophy, failed to gain a footing, while her health was irrevocably damaged by poverty and the grind of her work life. “Anyone who dreams of wealth and fame might be warned by this story of a woman who struggled so hard to make money that by the time she reached her goal she could not longer appreciate its benefits,” writes Louisa’s biographer, Susan Cheever writes.

Louisa never regained her health after the success of Little Women, but her later years weren’t as dismal as it may seem. When her sister May died in Europe in 1879, Louisa helped raise her daughter, Louisa May Nieriker. Louisa’s hard work and passion lived on in her niece — and in the books that survived her. Without her unusual family, there would have been no Louisa May Alcott — an author whose work sprang from an extraordinary life.

Thank you for reading this post How Louisa May Alcott’s Real-Life Family Inspired ‘Little Women’ at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: