You are viewing the article The Story of Security Guard Richard Jewell at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Early in the morning of July 27, 1996, amid the hoopla of the Summer Olympics that made Atlanta, Georgia, the center of the world for a fortnight, security guard Richard Jewell was working his beat at downtown Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park when he noticed an olive-green backpack beneath a bench.

After nobody claimed the pack, Jewell and an associate summoned a bomb squad, who confirmed their worst fears. Jewell immediately dashed into the neighboring five-story sound tower and pushed out the technical crew immersed in their jobs, before the 40-pound pipe bomb detonated in a deafening blow.

One woman was killed by shrapnel, a cameraman suffered a fatal heart attack and 111 were injured, but Jewell was quickly credited with discovering the deadly device and saving countless more lives.

The once anonymous security guard found his life turned upside down with the crush of attention that celebrated his heroism, though he insisted he simply doing his job. Days later, he found his life turned upside down again, the same devotion to his job having rendered him the FBI’s chief suspect and a media punching bag.

Early in his career, Jewell often found himself in trouble

Richard Allensworth Jewell was born Richard White in Danville, Virginia, on December 17, 1962. His parents split when he was four years old, and his mother, Bobi, married insurance executive with the now-familiar surname, before the family moved to Atlanta.

According to profiles in Vanity Fair and Atlanta, Jewell was an earnest, helpful type who worked as a crossing guard and operated the movie projector in the library, but seemingly had few friends in high school. Afterward, he briefly pursued a career as a mechanic, before landing a job as a supply room clerk at the Small Business Administration, where he met lawyer Watson Bryant, who would later serve a crucial role in defending him.

Yearning to enter law enforcement, Jewell was hired as a jailer in the Habersham County sheriff’s department, in northeastern Georgia, in 1990. He also took up a side job as a security guard of the apartment complex he called home, and it was here that his zealousness for the job first landed him in trouble: After busting a couple making too much noise in a hot tub, Jewell was charged with impersonating an officer, placed on probation and ordered to undergo a psychological evaluation.

Jewell regained his standing in the department and even earned a promotion to deputy sheriff, but after crashing his patrol car in 1995 while allegedly pursuing a suspicious vehicle, he resigned instead of accepting the demotion back to jailer.

In a new job as a campus security officer at nearby Piedmont College, Jewell made enemies within the student body for breaking up parties and reporting offending students to their parents, and angered his superiors for going beyond his jurisdiction to arrest speeding motorists on the highway. He resigned in May 1996, and with his mother scheduled to undergo foot surgery, he returned to Atlanta to live with her and find a new job.

The FBI attempted to trick him into making a videotaped confession

As Jewell was adjusting to life as America’s hero du jour in late July, the president of Piedmont College informed the FBI of his previous unpleasant experiences with the security guard who was too eager to make campus arrests. The FBI went digging for more info, soon uncovering his record in Habersham County which included the court-ordered psychological evaluation.

On July 30, after an early interview with Katie Couric on Today, Jewell received a visit from two FBI agents who said they were making a training video. He agreed to go along with them to headquarters and consented to a videotaped interview, but grew suspicious after the agents attempted to have him sign a waiver of rights.

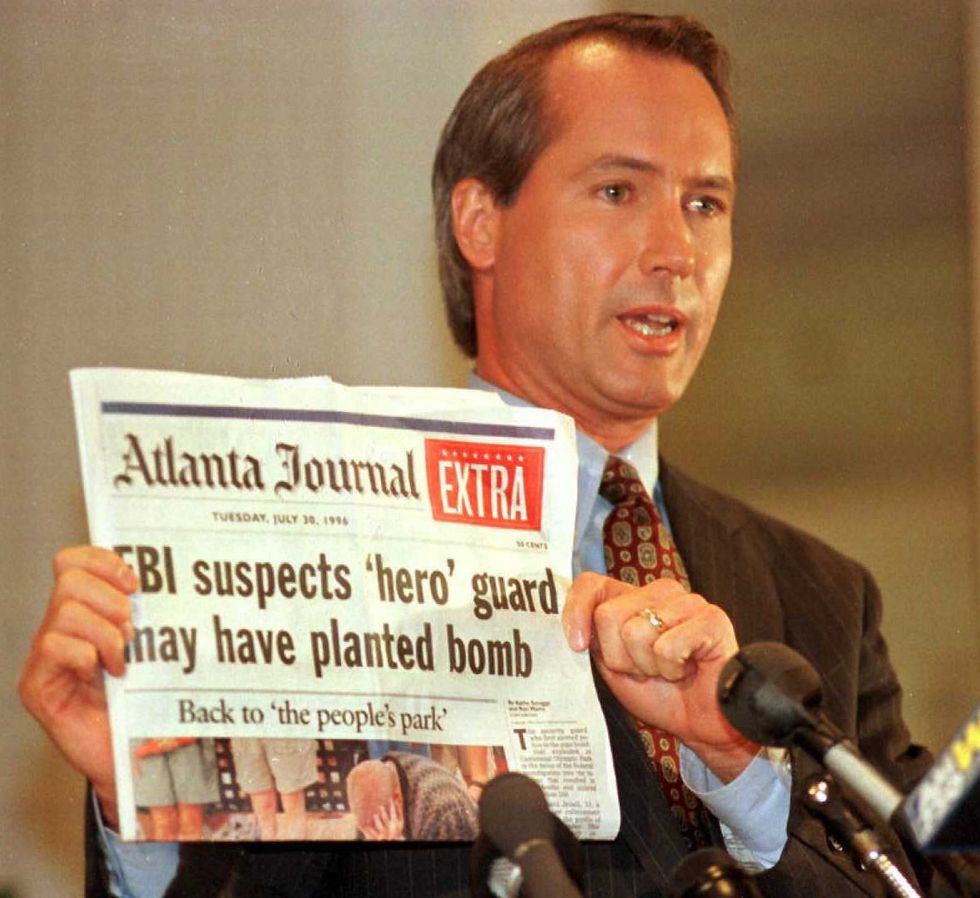

Meanwhile, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution had spilled the beans with an afternoon edition that proclaimed FBI SUSPECTS ‘HERO’ GUARD MAY HAVE PLANTED BOMB on the front page. Jewell returned to a media horde camped outside his mother’s apartment building, only to turn on the TV and see Tom Brokaw announce to the world that he was the lead suspect in the case and likely to be arrested soon.

The following day, Jewell helplessly waited outside his building as FBI agents rooted through his apartment for evidence that did not exist. Pictures of the portly, beleaguered security guard sitting on his steps only fueled the ugly media caricature that was beginning to take shape, one that portrayed him as an unmarried, 33-year-old who lived with his mother and desperately grasping for a shred of glory.

Jewell’s lawyers mounted an aggressive public defense

Fortunately, Jewell had his old friend Bryant in his corner. Although his professional specialties were more business-related, Bryant possessed enough of a firebrand’s spirit to passionately defend Jewell on television, and enough contacts in the industry to reel in a prominent criminal attorney and two more to handle civil litigations.

As Jewell and his mother lived their lives under virtual house arrest, passing notes to one another out of fear that their conversations were being recorded, the legal team went on the offensive, releasing the results of a polygraph test that showed the suspect’s innocence. In late August, during the Democratic National Convention, Jewell’s lawyers had Bobi deliver an impassioned plea to the Justice Department to clear her son of wrongdoing.

As the investigation stretched into its second month, with nothing to bolster the government’s case, public sentiment began turning in Jewell’s favor. In late September, 60 Minutes aired a highly sympathetic piece that cut through the caricatures, showing Jewell under tremendous strain from the unwanted media attention and the FBI vans trailing him whenever he left his apartment.

Still, it would be another month before the FBI offered a lifeline and declared that Jewell was no longer a suspect. In a press conference held on October 28, he cited the 88 days he had spent in the public eye as the No. 1 suspect, noting: “I hope and pray that no one else is ever subjected to the pain and the ordeal that I have gone through. … I thank God it is ended and that you now know what I have known all along: I am an innocent man.”

He reached settlements with several media outlets

Jewell subsequently launched defamation lawsuits against an array of media outlets for their portrayals of him, with the settlements helping to compensate for legal fees and a year spent without a job. He eventually returned to the law-enforcement work he loved in towns throughout Georgia, and enjoyed good fortune in the romance department by meeting the social worker Dana, who would become his wife.

Some closure came when Eric Robert Rudolph was sentenced to life in prison for the Olympic (and other) bombings in 2005. One year later, Jewell earned an official commendation from Georgia Governor Sonny Perdue for his heroic actions at Centennial Park that helped stave off an utter catastrophe. He soon was suffering from significant health issues, however, and died in August 2007 of complications from diabetes.

Although his public image continues to trend upward, with the 2019 Clint Eastwood movie highlighting his life and a plaque in his honor at Centennial Park, Jewell never shook the feeling that his mistreatment at the hands of the FBI and the media had robbed him of something precious.

“For that two days, my mother had a great deal of pride in me – that I had done something good and that she was my mother, and that was taken away from her,” he said in an AP interview the year before his death. “She’ll never get that back, and there’s no way I can give that back to her.”

Thank you for reading this post The Story of Security Guard Richard Jewell at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: