You are viewing the article John Quincy Adams at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

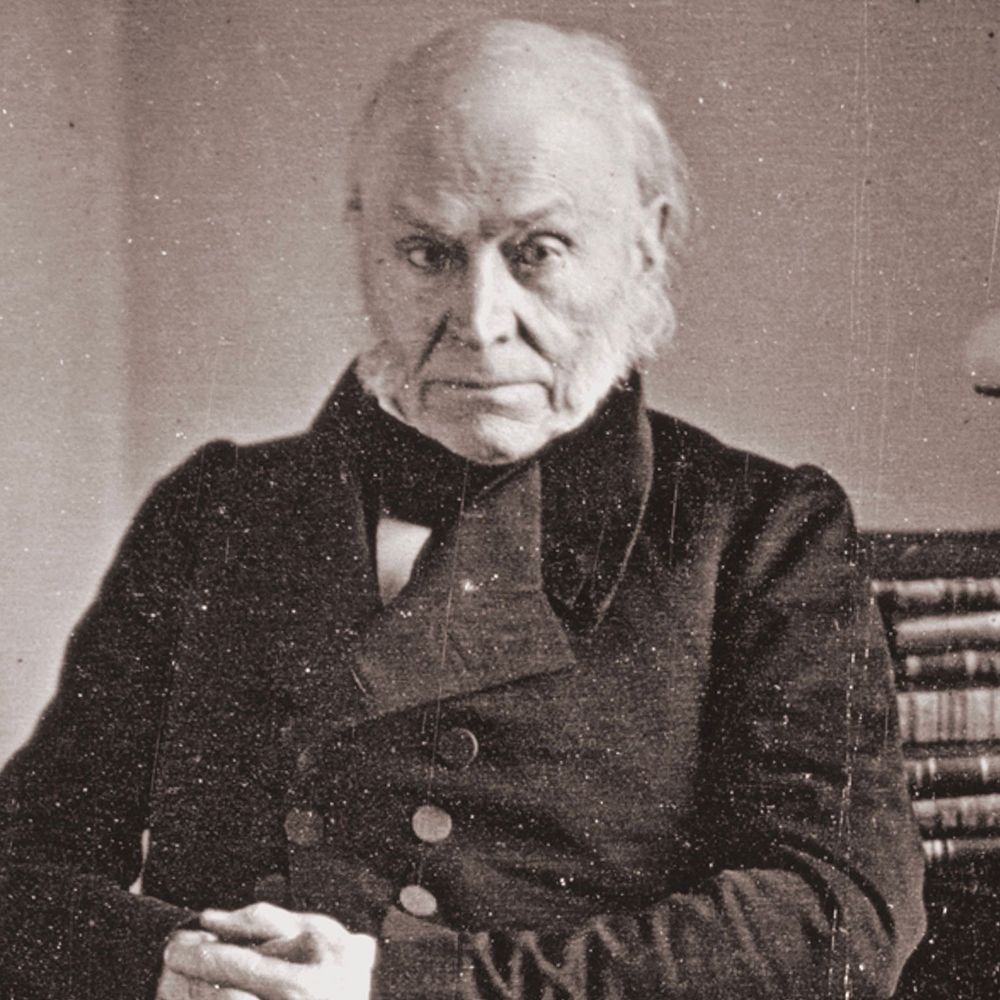

John Quincy Adams, the son of America’s second president, John Adams, belonged to a rare breed of individuals who were truly dedicated to serving their country. Born on July 11, 1767, in Braintree, Massachusetts, Adams spent his entire life in the public eye, living through one of the most crucial periods in American history. Renowned for his intellect, political acumen, and uncompromising principles, John Quincy Adams left an indelible mark on American politics as the nation’s sixth president. This introduction will delve into the life, achievements, and enduring legacy of this influential leader, shedding light on his contributions to shaping the United States as we know it today.

(1767-1848)

Who Was John Quincy Adams?

John Quincy Adams was the eldest son of President John Adams and the sixth president of the United States. In his pre-presidential years, Adams was one of America’s greatest diplomats (formulating, among other things, what became the Monroe Doctrine); in his post-presidential years, he conducted a consistent and often dramatic fight against the expansion of slavery. Though full of promise, his presidential years were difficult. He died in 1848 in Washington, D.C.

Early Life

Though he was one of few Americans to be so prepared to serve as president of the United States, Adams’ best years of service came before and after his time in the White House. Born on July 11, 1767, in Braintree, Massachusetts, John Quincy was the son of John Adams, a prodigy of the American Revolution who would become the second U.S. president just before his John Quincy’s 30th birthday, and his wife, future first lady Abigail Adams.

As a child, Adams witnessed firsthand the birth of the nation. From the family farm, he and his mother watched the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775. At age 10, he traveled to France with his father, who was securing aid during the Revolution. By age 14, Adams was receiving “on-the-job” training in the diplomatic corps and going to school. In 1781, he accompanied diplomat Francis Dana to Russia, serving as his secretary and translator. In 1783, he traveled to Paris to serve as secretary to his father, negotiating the Treaty of Paris. During this time, Adams attended schools in Europe and became fluent in French, Dutch and German. Returning home in 1785, he entered Harvard College and graduated in 1787.

Early Political Career

In 1790, Adams became a practicing attorney in Boston. As tensions mounted between Britain and France, he supported President George Washington’s neutrality policy of 1793. President Washington appreciated young Adams’ support so much that he appointed him U.S. minister to Holland. When his father was elected president in 1797, he appointed his son U.S. minister to Prussia. On the way to his post, Adams traveled to England to wed Louisa Catherine Johnson, the daughter of Joshua Johnson, the first U.S. consul to Great Britain.

After his father lost his bid for a second term in 1800, he recalled his son from Prussia. In 1802, Adams was elected to the Massachusetts legislature, and one year later, he was elected the U.S. Senate. Like his father, Adams was considered a member of the Federalist Party, but in truth, he was never a strict party man. During his time in the Senate, he supported the Louisiana Purchase and President Thomas Jefferson’s Embargo Act—actions that made him very unpopular with other Federalists. In June 1808, Adams broke with the Federalists, resigned from his Senate seat and became a Democratic-Republican.

Adams returned to the diplomatic corps in 1809, when President James Madison appointed him the first officially recognized minister to Russia (Francis Dana was never officially accepted as a U.S. ambassador by the Russian government). In 1814, Adams was recalled from Russia to serve as chief negotiator for the U.S. government during the Treaty of Ghent, settling the War of 1812. The following year, Adams served as minister to England, a position his father had held 30 years earlier.

In a post he was most suited for, Adams served as secretary of state in President James Monroe’s administration from 1817 to 1825. During this time, he negotiated the Adams-Onis Treaty, acquiring Florida for the United States. He also helped negotiate the Treaty of 1818, settling the long-standing border dispute between Britain and the United States over the Oregon Country, and initiating improved relations between Great Britain and its former colonies.

Monroe Doctrine

By age 50, Adams had amassed a very impressive record of public service, but perhaps his most notable and enduring achievement was the Monroe Doctrine. After the Napoleonic wars had ended, several Latin American colonies of Spain rose up and declared independence. A defining moment for the United States, Adams crafted the Monroe Doctrine, which stated the United States would resist any European country’s efforts to thwart independence movements in Latin America; the doctrine, first introduced in 1823, served to justify U.S. intervention in Latin America throughout the late 19th and most of the 20th centuries.

Presidential Election of 1824

By 1824, Adams was well-positioned to be the next president of the United States. However, the political climate had changed the way presidents were elected at the time; only the Democratic-Republican Party was viable and five candidates emerged, each representing different sections of the country. Running against Adams were Southerners John C. Calhoun and William Crawford, and Westerners Henry Clay and Andrew Jackson. In addition, by the 1824 election, 18 of 24 states had moved to choose electors to the Electoral College by popular vote instead of to state legislatures.

In the Electoral College vote, no one candidate had a clear majority and, subsequently, the election was sent to the House of Representatives. Clay threw his support to Adams, who was elected on the first ballot. Adams’ victory shocked Jackson, who had won the popular vote and fully expected to be president. When Adams later appointed Clay secretary of state, Jackson Democrats cried “corrupt bargain,” and were enraged at the seemingly quid pro quo arrangement.

John Quincy Adams Presidency

Adams entered the presidency with several debilitating political liabilities. He possessed the temperament of his father: Aloof, stubborn and ferociously independent in his convictions. As president, Adams failed to develop the political relationships needed—even among members of his own party—to effect significant change. It didn’t help that his political opponents were set on making him a one-term president.

In his first year in office, Adams proposed several far-sighted programs that he felt would promote science, as well as encourage a spirit of enterprise and invention in the United States; these goals included building a network of highways and canals to link the different sections of the country, setting aside public lands for conservation, surveying the entire U.S. coast and building astronomical observatories. Adams also saw the need for practical solutions to universal problems, thusly calling for the establishment of a uniform system of weights and measures and improving the patent system.

While these may have been admirable goals for an aspiring nation, they were considered overambitious and unrealistic for the United States in the 1820s. Adams’ proposals were met with scorn and derision by political opponents; critics charged that the president’s policies would enlarge the powers and influence of the federal government at the expense of the state and local governments, and some accused Adams of promoting programs to enhance the elite and neglect the common people. In the midterm election of 1826, Jacksonian opponents won majorities in both Houses of Congress. As a result, many of Adams’ initiatives either failed to pass legislation or were woefully underfunded.

The election of 1828 was an especially bitter and personal affair. As was the tradition, neither candidate personally campaigned, but supporters conducted ruthless attacks on the opposing candidates. The campaign reached a low point when the press accused Jackson’s wife, Rachel, of bigamy. Adams lost the election by a decisive margin, and he left Washington without attending Jackson’s inauguration.

Final Years and Death

Adams did not retire from public life after leaving the presidential office. In 1830, he ran for and won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, once again distinguishing himself as a statesman of the first order. In 1836, Adams focused his long-standing anti-slavery sentiment on defeating a gag-rule instituted by Southerners to stifle debate. In 1841, he argued in front of the Supreme Court on behalf of escaped African slaves in the famous Amistad case, and won the release of the captives.

On February 21, 1848, in his last contribution to his country, Adams was on the floor of the House of Representatives, arguing to honor U.S. Army officers who had served in the Mexican-American War (he opposed the war, but felt that the U.S. government was obligated to honor its veterans). During the event, Adams suddenly collapsed, suffering from a massive cerebral hemorrhage. He was taken to the Speaker’s Room in the Capitol Building, where he died two days later, on February 23, 1848.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: John Quincy Adams

- Birth Year: 1767

- Birth date: July 11, 1767

- Birth State: Massachusetts

- Birth City: Braintree

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: John Quincy Adams was the sixth president of the United States. He was also the eldest son of President John Adams, the second U.S. president.

- Industries

- Civil Rights

- Politics and Government

- Law

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- Schools

- University of Leiden

- Death Year: 1848

- Death date: February 23, 1848

- Death State: Washington, D.C.

- Death Country: United States

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn’t look right,contact us!

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: John Quincy Adams Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/john-quincy-adams

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 19, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

QUOTES

- You will never know how much it has cost my generation to preserve your freedom. I hope you will make good use of it.

- America does not go abroad in search of monsters to destroy.

In conclusion, John Quincy Adams was a significant figure in American history. From his early years as a diplomat to his time as the sixth president of the United States, Adams made lasting contributions to the growth and development of the nation. His diplomatic skills and commitment to justice were evident in his negotiations and treaty signings, as well as in his fight against slavery. Despite facing numerous challenges and criticisms during his presidency, Adams remained steadfast in his dedication to serving the American people. While his presidency may have been relatively short-lived, his impact on shaping the nation’s foreign policy and his unwavering commitment to his principles cemented his place in history as a respected and influential leader.

Thank you for reading this post John Quincy Adams at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. John Quincy Adams presidency

2. John Quincy Adams biography

3. John Quincy Adams quotes

4. John Quincy Adams family

5. John Quincy Adams accomplishments

6. John Quincy Adams early life

7. John Quincy Adams political career

8. John Quincy Adams education

9. John Quincy Adams election

10. John Quincy Adams foreign policy