You are viewing the article 5 Powerful and Influential Native American Women at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

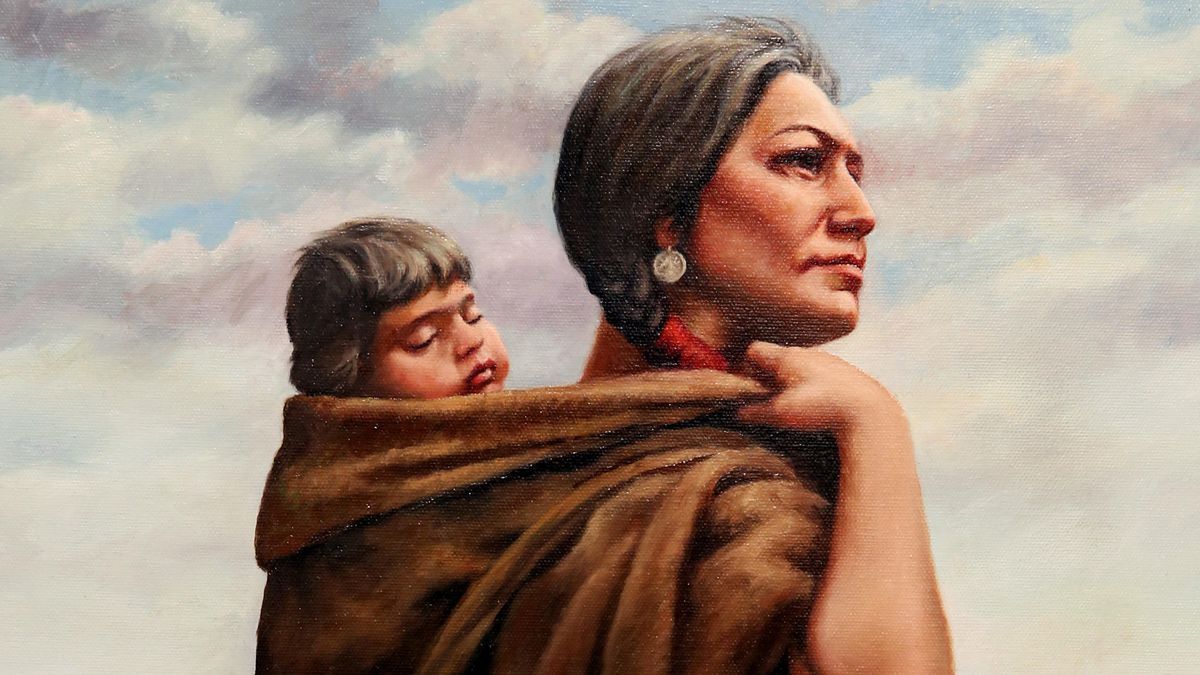

Throughout history, Native American women have played pivotal roles in shaping their communities, advocating for their rights and culture, and inspiring generations to come. Although often overlooked or marginalized in mainstream narratives, these powerful and influential women have left an indelible mark on Native American history. From warriors and political leaders to artists and activists, these women have defied societal expectations, broken barriers, and made significant contributions to their tribes and the world at large. In this article, we will explore the lives and legacies of five Native American women who have made a lasting impact, highlighting their strength, resilience, and determination in the face of adversity. Through their stories, we hope to shed light on their invaluable contributions and honor their place in Native American history.

In the annals of Native American history, there have been some formidable women who fought fearlessly in battle, served as committed leaders, undertook dangerous journeys and saved lives. Here are five of the most powerful and influential Native American women of all time:

Nanye-hi (Nancy Ward): Beloved Woman of the Cherokee

Nanye-hi was born into the Cherokee Wolf clan circa 1738. In 1755, she stood by her husband during a fight against the Creeks, chewing the lead for bullets in order to provide his ammunition with deadly ridges. When her husband was fatally shot, Nanye-hi grabbed a rifle, rallied her fellow fighters and entered the battle herself. With her on their side, the Cherokee won the day.

These actions led to Nanye-hi being named Ghighau (Beloved Woman) of the Cherokee, a powerful position whose duties included leading the Women’s Council and sitting on the Council of Chiefs. Nanye-hi also took part in treaty talks (to the surprise of male colonists when they were on the other side of the bargaining table).

As the years progressed, some Cherokee wanted to fight the Europeans who continued to crowd into their land. But Nanye-hi, who likely realized the Cherokee couldn’t win against the numerous and well-supplied colonists, thought the two sides needed to learn to live together (she practiced coexistence herself, marrying an Englishman, Bryant Ward, in the late 1750s, which led to her being known as Nancy Ward). At a 1781 treaty conference, Nanye-hi declared, “Our cry is all for peace; let it continue. This peace must last forever.”

Seeking peace didn’t stop Nanye-hi from recognizing the dangers of ceding Cherokee territory — in 1817, she made an unsuccessful plea not to give up more land. When she died in 1822, she’d spent years trying to help her people acclimate to a changing world.

Sacagawea: The Woman Who Made Lewis and Clark a Success

A Shoshone Indian born circa 1788, Sacagawea was kidnapped by the Hidatsa when she was around 12 years old. Eventually, she and another captive were acquired by and married to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian trader.

When Charbonneau was hired as a translator for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark also wanted to take advantage of Sacagawea’s linguistic knowledge (she could speak both Shoshone and Hidatsa). Sacagawea set out with the expedition on April 7, 1805, only two months after giving birth. She took her son, Jean Baptiste, on the journey, where the presence of mother and child was an indisputable asset — as war parties didn’t take along women and children, the group wasn’t seen as a threat by the tribes they encountered.

Sacagawea assisted the expedition in other ways: When a panicked Charbonneau almost capsized a boat, she saved navigational tools, supplies and important papers. She was able to locate edible and medicinal roots, plants and berries. The landmarks she remembered also proved useful in their travels.

When the group returned to the Hidatsa-Mandan villages in 1806, Sacagawea didn’t receive any pay (her husband got $500, as well as 320 acres of land). Clark acknowledged the unfairness of this in an 1806 letter to Charbonneau: “[Y]our woman who accompanied you that long dangerous and fatigueing rout to the Pacific Ocian and back diserved a greater reward for her attention and services on that rout than we had in our power to give her….”

Sacagawea died in 1812, soon after giving birth to a daughter, Lisette. Indicating how much he’d appreciated her, it was Clark who took responsibility for Sacagawea’s children.

READ MORE: Lewis and Clark: How the Explorers’ Corps of Discovery Transformed North America

Sarah Winnemucca: An Outspoken Advocate

Born circa 1844 in present-day Nevada, Sarah Winnemucca — the daughter and granddaughter of Northern Paiute chiefs — learned English and Spanish as a child, in addition to three Indian dialects. In the 1870s, these abilities led to her serving as an interpreter at Fort McDermitt and then on the Malheur Reservation.

After the Bannock War of 1878 — during which Winnemuccca showed her mettle by working as an army scout, and also rescued a group of Paiute that included her father — some Paiute were forcibly relocated to the Yakima Reservation. Winnemucca, who had already seen how American Indians were at the mercy of sometimes corrupt reservation agents, decided to advocate for Native American land rights and other systemic improvements.

In 1879, Winnemuccca lectured in San Francisco. The next year she met with President Rutherford B. Hayes in Washington, D.C. Winnemucca also became the first Native American woman to produce a published book, Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims (1883). The work included powerful statements such as: “For shame! For shame! You dare to cry out Liberty, when you hold us in places against our will, driving us from place to place as if we were beasts.”

The U.S. government committed to reforms, including a return to Malheur for the Paiute. However, in the end, nothing changed.

Winnemucca died in 1891. Despite the setbacks she’d encountered, she was a forceful advocate for her people.

Lozen: A Gifted Warrior

In the 1870s, many Apache chafed at being forced to live on reservations. A group headed by Victorio, leader of the Warm Springs Apache, escaped from the San Carlos Reservation in 1877. Among the warriors at Victorio’s side as they eluded both U.S. and Mexican authorities was his younger sister, Lozen.

Though it was extremely unusual for an unmarried woman to ride as a warrior, Lozen was an integral part of the group, thanks in part to her special skills. Born in the late 1840s, Lozen had participated in a puberty rite that gave her the ability to track Apache foes. According to oral histories, the main source of information about Lozen was that her hands would tingle when she faced the direction of an enemy, and the strength of this sensation indicated how close or far away her opponents were. Victorio’s description of Lozen shows how much she was appreciated: “Strong as a man, braver than most and cunning in strategy, Lozen is a shield to her people.”

Victorio and most of his followers were killed by Mexican soldiers in 1880. But Lozen’s abilities hadn’t failed; she was away helping a pregnant woman. In fact, many believed that, had she been there, Lozen could have saved the day.

After joining Geronimo and his band, Lozen continued to be an asset, at one point diving into the heat of battle to get badly needed bullets. She was also sent — with Dahteste, another female warrior — by Geronimo to negotiate with U.S. authorities. When these talks finally resulted in Geronimo’s surrender in 1886, Lozen was among those imprisoned in Florida. She was then sent to Alabama’s Mount Vernon Barracks, where she died of tuberculosis in 1889.

Lozen was buried in an unmarked grave, but she was never forgotten and remains an honored figure in Apache history.

Susan La Flesche: The Healer

Born in 1865, Susan La Flesche grew up on the Omaha reservation. During her childhood, she saw a white doctor refuse to treat an ailing American Indian woman. This spurred La Flesche to become a physician herself. In 1889, she was the first female Native American to earn a medical degree in the United States.

After finishing her internship, La Flesche started work on the vast (30-by-45 mile) Omaha reservation. She took care of about 1,300 patients who suffered from ailments that included tuberculosis, diphtheria and influenza. A worn-down La Flesche had left this position by 1894, though she continued to see patients in private practice and served as a medical missionary. She also married and had two children.

In 1909, as a trust period that had limited Omaha control over their property was about to end, the federal government decided that these landowners still lacked the ability to manage their property. La Flesche felt that “the majority of the Omaha are as competent as the same number of white people” and led a delegation to Washington, D.C., to make this case. This resulted in the Omaha being allowed to control their land.

However, La Flesche’s focus remained on improving the health of the Omaha; through the years she treated most of the population. She also helped raise the funds to open Walthill Hospital in 1913. After her death in 1915, the facility was renamed the Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte Memorial Hospital.

In conclusion, the stories of these five powerful and influential Native American women serve as testament to the resilience, intelligence, and determination of Indigenous communities. From leaders and activists to artists and scholars, these women have made significant contributions to their respective fields, while also working tirelessly to preserve and elevate Native American culture. Their stories remind us of the enduring strength and power of Indigenous women, who continue to inspire and lead both within their communities and beyond. By acknowledging and amplifying these stories, we can challenge stereotypes, support the empowerment of Native American women, and work towards a more inclusive and equitable society for all.

Thank you for reading this post 5 Powerful and Influential Native American Women at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. Notable achievements of Chief Wilma Mankiller, the first female Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation

2. Influence and contributions of Maria Tallchief, the first Native American prima ballerina

3. Significant accomplishments of Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte, the first Native American woman to earn a medical degree

4. Inspirational life and leadership of Sarah Winnemucca, a prominent advocate for Native American rights

5. Historical impact and legacy of Pocahontas, a Native American woman who played a crucial role in the English colonization of Jamestown

6. The remarkable story of Mary Golda Ross, one of the first Native American women to work as a professional aerospace engineer

7. Cultural significance and artistic contributions of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a renowned Native American painter

8. Activism and advocacy of Winona LaDuke, a prominent environmentalist and Indigenous rights activist

9. The life and work of Louise Erdrich, an acclaimed Native American author and poet

10. Recognition and achievements of Suzanne Harjo, a leading advocate for the rights and cultural preservation of Native American communities.