You are viewing the article 9 Key Figures of the Harlem Renaissance at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

As the Great Migration of African Americans made its way north, New York City’s Harlem neighborhood became a vibrant hotspot for musicians, writers, entertainers and thinkers. The collection of talent, all within a few city blocks, became known as the Harlem Renaissance. Lasting between the 1910s and the mid-1930s, the influence of the time is still felt today.

Here are nine of the most prominent figures of the cultural movement:

Langston Hughes

One of the leaders of the Renaissance, Langston Hughes made his mark by using his art to show the universal experience of the Black community.

The Missouri-born poet and writer lived all across America before spending a year at Columbia University and later finished his education at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. His first book of poetry was published in 1926 at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, with his first novel following soon after.

According to critic Donald B. Gibson, Hughes “differed from most of his predecessors among black poets… in that he addressed his poetry to the people, specifically to Black people. During the twenties when most American poets were turning inward, writing obscure and esoteric poetry to an ever decreasing audience of readers, Hughes was turning outward, using language and themes, attitudes and ideas familiar to anyone who had the ability simply to read.”

Hughes died in 1967 of complications of prostate cancer at 65. To honor him, his Harlem residence was given landmark status by the New York City Preservation Commission and the street he lived on was renamed “Langston Hughes Place.”

READ MORE: 10 of Langston Hughes’ Most Popular Poems

Zora Neale Hurston

An author, playwright and filmmaker, Zora Neale Hurston celebrated the culture of the Black rural South like few others. Her love of the South came from her own childhood growing up in the Orlando suburb or Eatonville, the first all-Black town in the country where she was never treated differently or inferior.

Though Hurston’s idyllic upbringing came to an end when she turned 13 and her beloved mother died, the writer continued impressing people everywhere she went and eventually made her way north to Harlem, becoming a friend of Hughes.

The two collaborated on a play together, published posthumously, and Hurston gained recognition for her novels and investigations of voodoo culture.

She died in 1960 at 69, with her latest book, written in 1931, finally published in 2018. Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” tells the story of Cudjo Lewis, who was believed to be the last survivor of the final slave ship that brought Africans to America.

READ MORE: 10 Best-Selling Black Authors Who Shaped Literary History

Louis Armstrong

Known as one of the founding fathers of jazz, Louis Armstrong revolutionized the genre with the work that came out of the Harlem Renaissance.

Growing up in New Orleans, Armstrong was constantly exposed to some of the best jazz musicians in the country. Though his daily life was hard as his single mother struggled to raise him, and he ended up in an orphanage, his love of music and natural talent propelled him to the ranks of some of America’s most famous musicians.

After he moved to New York City in 1924 to join the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, Armstrong’s unique, soulful and lively solos changed the course of jazz to focus on individual musicians experimenting with sound.

His small group recordings from 1925 to 1928, all during the Renaissance, made Armstrong the most influential musician in jazz, and his singing brought his work to world-wide stardom. Armstrong would later be responsible for enduring hits like “What A Wonderful World” and “Hello Dolly.”

READ MORE: How Louis Armstrong Revolutionized American Music

Marcus Garvey

Few activists had the impact Marcus Garvey brought to the African American community in a short span of time — and all out of Harlem. The Jamaican-born leader took residence in Harlem and began a series of innovative projects and movements that focused on the Black working class. While Garvey was seen as a radical figure that advocated for the return to Africa of many dark-skinned African Americans, his motives were to install Black pride in a community oppressed by racism.

In 1914, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), later making Liberty Hall in Harlem its headquarters. By the 1920s, the UNIA had over 700 chapters across America and Garvey commanded influence.

In August 1920, delegates from around the world packed the hall for a convention, and more than 25,000 people later marched from Harlem to Madison Square Garden, where Garvey held a rally.

Like many African American leaders at the time, Garvey became the target of the U.S. government and he was convicted and imprisoned for mail fraud in 1923. He was later pardoned by President Calvin Coolidge and deported back to Jamaica in 1927.

A tribute to his contribution forever stands in Harlem with Marcus Garvey Park, dedicated to nurturing the community he sought to improve.

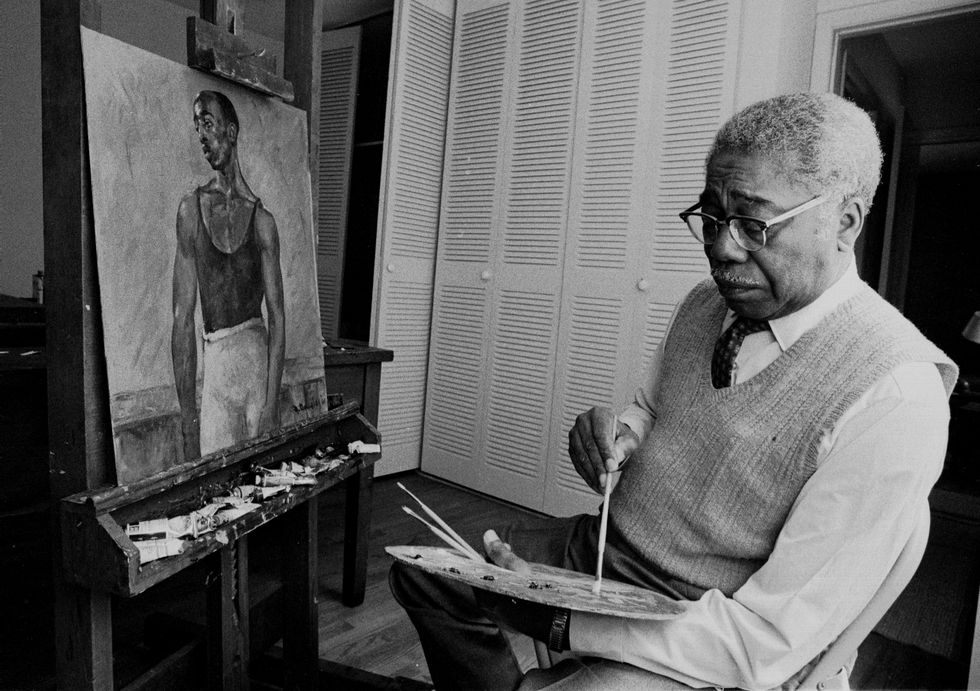

Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas has long been called the “Father of African Art” thanks to his impactful paintings that were shaped by the pillars of the Harlem Renaissance.

Douglas made his way to New York City from his native Kansas in search of the hubbub of talent he had heard about. Once there, Douglas made famous friends in fellow leaders W.E.B. Du Bois, Alain Locke and James Weldon Johnson, all of whom featured his work in famous publications and even their own books.

The artist was known for his dramatic geometric shapes and flat forms that he used to tell the story of the Black experience.

Douglas eventually made his mark on Harlem permanent with a mural on the New York Public Library’s 135th location entitled Aspects of Negro Life. The breathtaking piece shows three facets of the Black experience: a figure symbolizing the escape from slavery, one showing the economic hardships of African Americans and the third holding a saxophone, paying tribute to the rich opportunities Black artists had thanks to the Renaissance.

Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen had a vibrant life after becoming the adopted son of Reverend Frederick A. Cullen, the pastor of Harlem’s largest congregation when he was 15.

The poet was quickly influenced by the bedrock of talent around him and had already appeared in national magazines before he graduated from New York University in 1925. He published his first book of poems, Color, that same year. His poems explored modern racial injustice at the time using the classical structures associated with white poets.

Tight with a circle of celebrated writers, Cullen became the assistant editor of Opportunity magazine, an academic journal published by the National Urban League.

Cullen later etched his name into Black high society when he married Yolanda Du Bois in 1928, the daughter of civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois.

Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith became known as the “Empress of the Blues” thanks to her captivating and powerful vocals.

Smith was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and was working as a blues singer by the time she was 18. She soon joined the Rabbit Foot Minstrels and met the legendary Ma Rainey, who took Smith under her wing.

Smith eventually made her way to New York where her first release, “Down-Hearted Blues,” became a huge hit. She went on to record with legendary artists like Armstrong during her time in the Harlem scene.

While Smith’s popularity continued for some time, but toward the end of her life, she lost popularity. She died at 43 years old in 1937 from injuries sustained in a car accident.

READ MORE: Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey Forged a Powerful Friendship That Helped Bring Blues to the Mainstream

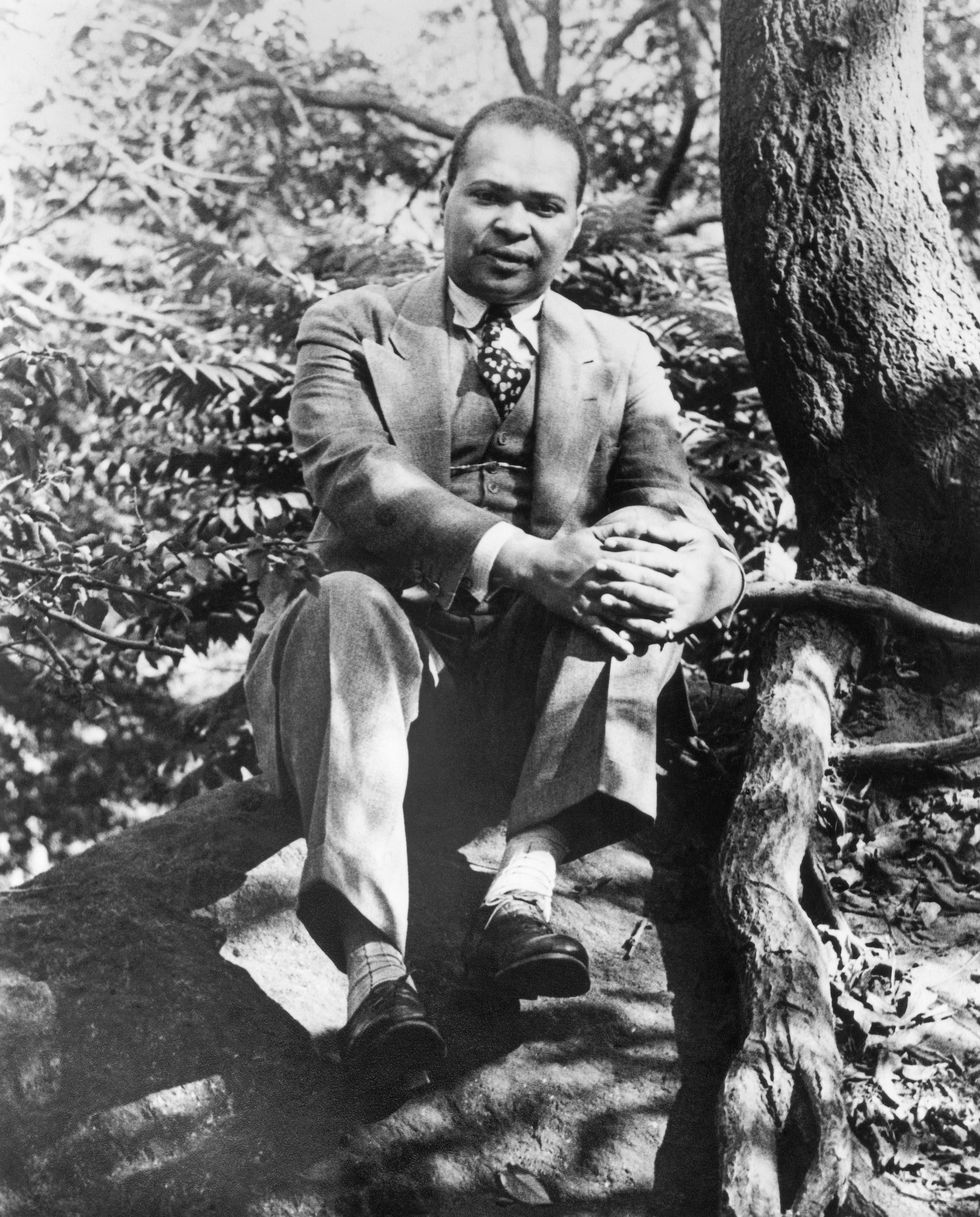

Sterling A. Brown

Poet Sterling A. Brown was welcomed into the Harlem Renaissance legacy after his first book Southern Road was published to critical acclaim.

Born in 1901 in Washington, D.C., Brown received a high-profile education at places like Williams College and Harvard University, later teaching at Howard University.

His work was influenced by African American music and his writings mused on race and class in America, like that of Hurston, Hughes and Cullen. Though the Great Depression kept him from being published again for decades, Brown eventually released his second book, The Last Ride of Wild Bill, in 1975.

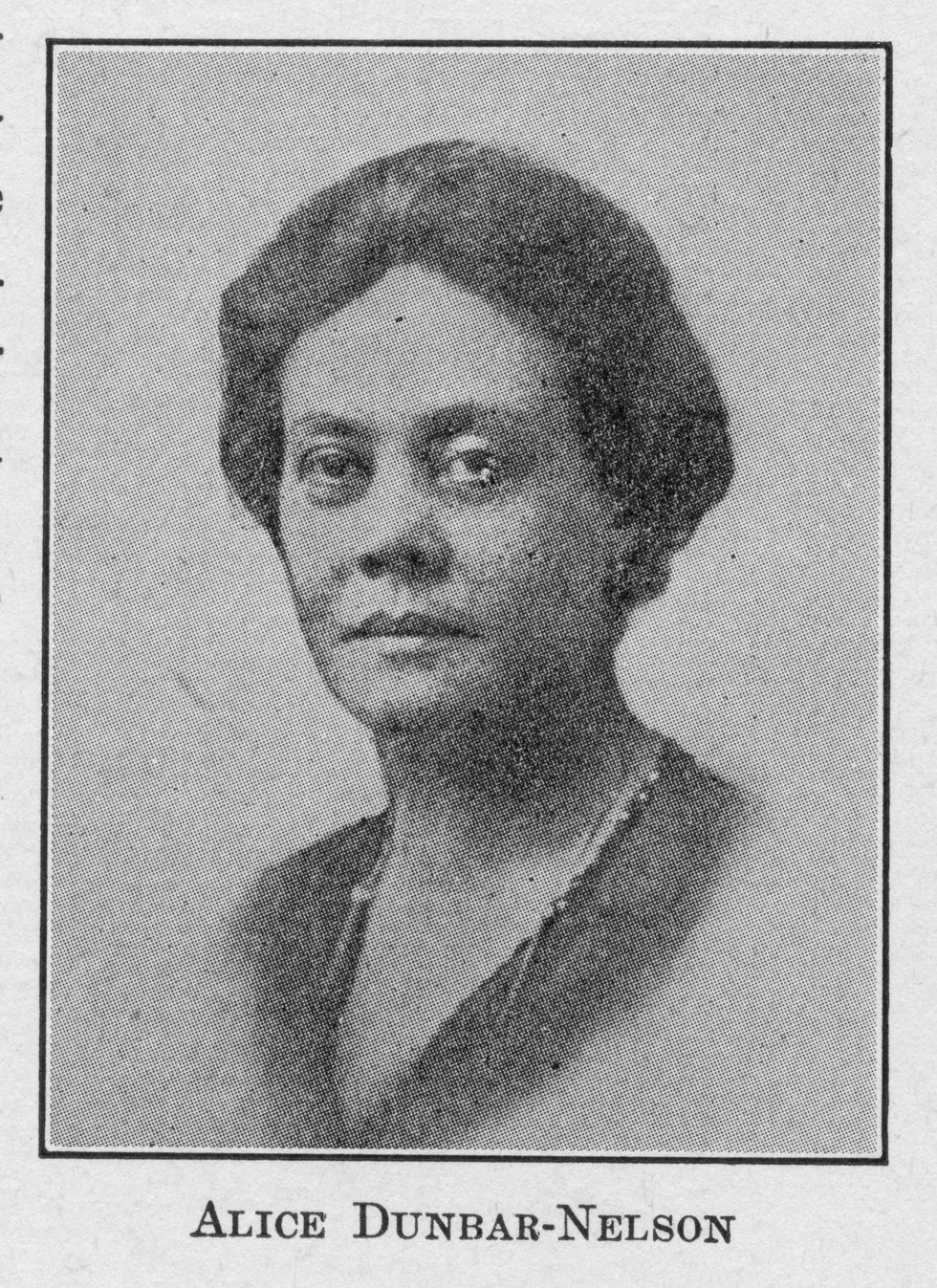

Alice Dunbar Nelson

Alice Dunbar Nelson was born to mixed-race parents in New Orleans, setting the tone for the nuanced take on race, gender and ethnicity she explored through her work.

A poet and activist, Dunbar Nelson’s first book, Violets and Other Tales (1985), was published when she was just 20 years old. A writer of many genres, Dunbar Nelson is most remembered for her prose. As one of the only female African American diarists of the era, she wrote about topics such as racism, sexuality and family.

She made her mark on the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance through her many reviews of writers like Hughes while living in the New York City neighborhood. Dunbar Nelson is also credited for helping establish the White Rose Mission in Harlem, a Christian, nonsectarian Home for Colored Girls and Women. The Mission also offered job placement for African Americans coming to the city in the post-Civil War migration.

Thank you for reading this post 9 Key Figures of the Harlem Renaissance at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: